Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that make an argument invalid. They occur when a conclusion does not logically follow from the premises, resulting in a non sequitur. These fallacies often rely on emotional appeals and falsehoods, making them particularly effective on those susceptible to confirmation bias. Regrettably, logical fallacies are commonly found in poor journalism and unscrupulous politics, while responsible journalism and politics strive to avoid them.

As part of the Intellectual Elements, logical fallacies play a crucial role in the Touchstone Truth Framework, a comprehensive system for developing critical thinking skills. Familiarizing oneself with logical fallacies can help improve one’s critical thinking skills by allowing self-assessment for flawed arguments and recognition of valid or invalid opposing arguments. Intellectual Elements are used within both the Three Truth Hammers and Four Mind Traps.

Issues with valid arguments on both sides can be more challenging to resolve, as seen in the abortion debate, where arguments center around defining the beginning of life. The various perspectives on when life starts, such as at conception, heartbeat detection, brain formation, or birth, all have valid arguments, making the discussion more intricate and requiring deeper examination of each argument’s validity.

On the other hand, issues with only one valid argument can be more easily resolved, as opposing arguments would rely on logical fallacies rather than sound reasoning.

Top 11 Logical Fallacies

The following list are in order of importance (my opinion). Notice each has the Latin translation. I love Latin, but my excuse for including it also includes the fact that it is common to include it when discussing logic. Why? Many still associate logic with the Latin language. For many centuries, Latin was considered the common language of the educated in the Western world and used to communicate in Western cultures around the world. In a real sense, Latin books and scrolls were the predecessor of the original intent of the internet. That is, for scholars to communicate among themselves around the world.

Who gets credit for first developing logic? Aristotle. Although great thinkers stand on the shoulders of their ancestors, Aristotle is the lucky man who frequently gets credit for first developing logic in the Western world. He called the subject analytics.

As you read a summary of each keep in mind that just because someone uses a logical fallacy does not mean they’re wrong about the argument, it just means they have yet to make a valid argument.

1. Personal Attack – “ad Hominem”

A.k.a. poisoning the well. With this fallacy, you use an insult as an argument. A variation of this fallacy is guilty by association.

Example 1,

“Liberals/Conservatives always say _____.”

Example 2,

“Obama’s preacher Jeremiah Wright said a few things I think were anti-American and bad, therefore Obama is anti-American and bad.”

Example 3,

“Trump is a Nazi.”

All of these are invalid arguments and say nothing. To respond, just point out the insult as a logical fallacy and simply ask if they want to present a valid argument. If mixed with other arguments, point out the name calling and only address the rest of the argument.

2. Appeal to Authority – “argumentum ad verecundiam”

With the appeal to authority fallacy, you use an authority you believe as the argument. The problem is that experts are not always right, therefore you should refer to the authority’s argument. In a world where both good and bad authorities can be right, or wrong, about any conclusion, you need to evaluate the

Good authority example,

“The CDC says vaccines do not cause autism.”

Most of us consider the CDC to be a great authority. The problem is that if one believes vaccines cause autism, they may accept this good authority, but they may not. If they don’t, you’ll have to refer them to the CDC justification for their conclusion.

Bad authority example,

“Alex Jones says the government is making people gay, by what they put in the water.”

It’s tempting to simply throwback an ad hominem attack,

“That person is a complete idiot and you should not listen to them ever!”

However, a better reply might be,

“Can you provide me with the argument or evidence the authority used to come up with their conclusion?”

When confronted with stupid, you have to reply by advancing the conversation if you wish to convert stupid to smart.

3. False Equivalence

A false equivalence is an equivalence made between two subjects based on flawed or false reasoning. This fallacy is committed when one shared trait between two subjects is assumed to show equivalence when it does not exist.

A false equivalence occurs when an anecdotal similarity is pointed out as equal, but are not. To be a false equivalence, the claim of equivalence must break down under scrutiny. This error is usually because of an oversimplification or because it is ignoring additional factors.

The pattern of a false equivalence is:

“X = a + b, and Y = a + c. Since they both contain a, X and Y are equal.”

When reduced to math, you can easily see that a false equivalence is bad math, bad logic. Just because two equations have the same value in them does not mean the two equations are equal. That’s silly and easily disproved. Likewise, just because two arguments have a thing in common does not mean they are equal. That too is silly and easily disproved.

4. Straw Man

With this fallacy, you hold up a position that someone does not hold, and then tear it down. Usually the position is weak or ridiculous and easily knocked down.

A good reply,

“You are attacking a position I do not hold. I am not arguing that _____. My position is _____.”

For example, one might argue that,

“Democrats want open borders which will allow criminals into America.”

The reality is that is an argument Democrats are not making. If we have open borders, then criminals would indeed come in more easily. That is true, but Democrats are not arguing for completely open borders.

A sample reply:

“You are attacking a position I do not hold. I am not arguing that I want open borders, nor am I arguing that I want to allow criminals into America. My position is that I want a lawful immigration policy that is consistent, not racist, and abides by international law including the Geneva convention.”

5a. Appeal to Ignorance — “argumentum ad ignorantiam”

With this fallacy, you use the fact that we do not know something to imply something else is either true or false. Ignorance (not knowing) is not evidence. Commonly said as,

“a lack of evidence is not evidence.”

Just because you can’t prove something, does not mean it’s true, nor false.

Example,

“Mueller has not released his report yet, therefore Trump did not collude with Russia.”

Example,

“We haven’t heard anything conclusive evidence that Trump conspired with Russia, therefore Trump did nothing wrong.”

Example against God’s existence,

“We have no evidence God exists, therefore God does not exist.”

Example for God’s existence,

“We cannot prove God does not exist, therefore God exists.”

5b. God of the Gaps

Similar to appeal to ignorance, the “God of the Gaps” occurs when gaps in scientific knowledge are taken as evidence or proof of God’s existence. Essentially, it involves using the lack of information or incomplete understanding in scientific explanations as a place to insert a supernatural explanation. This fallacy is particularly evident in discussions about phenomena that science has not fully explained yet, such as the origins of the universe or the complexities of biological processes.

For example, in debates about evolution, some may argue against its validity by pointing to the absence of complete fossil records for every stage of evolution from one species to the next. They might say,

“You can’t show exactly how these species evolved into each other; therefore, this gap in knowledge proves that a divine creator must have intervened.”

This argument focuses on specific uncertainties or undeveloped areas within evolutionary theory to discredit the extensive body of evidence supporting evolution, rather than addressing the overall scientific consensus and robust evidence that does exist.

The “God of the Gaps” fallacy is problematic because it relies on the current limitations of scientific understanding as supposed ‘proof’ of divine action, ignoring the potential for future discoveries and advancements that could fill these gaps. Moreover, it shifts the discussion away from scientific inquiry and evidence, turning it instead towards supernatural explanations that are not based on empirical evidence.

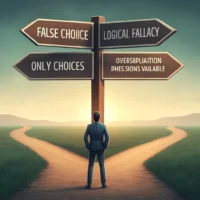

6. False Choice

A false choice is when you reduce the choices down to two or sometimes three choices but there are actually more choices available.

A false choice, also known as a false dilemma, false dichotomy, or even a Black and White Fallacy, is a type of logical fallacy—an error in reasoning. This fallacy occurs when an argument incorrectly presents only two options or outcomes in a situation, implying that these are the only possible choices when, in fact, other alternatives exist. The essence of a false choice lies in its oversimplification of complex issues, forcing an either/or decision that doesn’t accurately reflect the full spectrum of possibilities.

For example, consider the statement: “You’re either with us, or you’re against us.” This presents a situation as having only two opposing sides, ignoring any middle ground or nuanced positions that might exist. By simplifying scenarios in this manner, a false choice pressures individuals to make decisions without considering all available options, leading to potentially flawed conclusions.

7. Slippery Slope

A slippery slope argument one in which you take a reasonable position, and move it to the extreme. One thing doesn’t necessarily lead to the other.

A slippery slope argument, also known in some contexts as the Domino Theory, is a logical fallacy that suggests taking a minor action will lead to a series of related (and typically negative) consequences, without providing concrete evidence for such a catastrophic chain of events. This type of reasoning is problematic—or rather, it represents an error in logic—because it relies on speculative and often unfounded assumptions rather than on a solid, causal relationship between actions.

The main issue with slippery slope arguments is that they play on fear and exaggeration, distracting from rational and evidence-based discussion. By suggesting that one small step in a particular direction will inevitably lead to an extreme outcome, these arguments often discourage critical analysis of the initial action itself.

For example, consider the argument: “If we allow students to redo their assignments to improve their grades, next they’ll want to retake entire courses, and soon they’ll expect to get degrees without doing any work at all.” This statement assumes, without justification, that allowing assignment redos will lead down a path to complete academic disengagement, skipping over any number of intermediate steps where practical and reasonable limits could be established.

Identifying slippery slope arguments is crucial for reasoned discourse, as it helps separate realistic outcomes from exaggerated predictions, ensuring decisions are made based on facts and probabilities, not fear or hyperbole.

8. Circular Argument – “petitio principii”

A.k.a. begging the question. A circular argument repeats something assumed to be true in the conclusion. The first thing still needs to be proven. These fallacies are presumptuous.

Example,

“God’s miracles prove he exists because I have witnessed his glory all around me.”

A circular argument is the error where the conclusion of an argument is assumed in the premise. Essentially, the argument goes around in a circle by stating the same assertion in different words, without providing any actual evidence to support the conclusion. This makes the argument invalid as it relies on its own premise to prove itself, which fails to add new or conclusive information to the discourse. For example, if someone argues,

“Reading fiction is valuable because it is beneficial to read imaginative literature,”

they are using circular reasoning. The claim that fiction is valuable is merely restated as being beneficial, without explaining or proving why it is beneficial.

9. Hasty Generalization

insufficient evidence, stereotyping, overstatement such as

“all the time”

A hasty generalization is a logical fallacy that occurs when someone makes a broad conclusion based on insufficient or non-representative evidence. Essentially, this fallacy involves drawing a general rule from a single, often atypical, event or a small sample that is not large enough to hold up to statistical scrutiny. The error lies in the leap from an individual or minimal data points to a universal rule without considering all relevant variables or a sufficient amount of evidence.

For example, if someone visits a city for the first time, experiences poor service at a restaurant, and concludes,

“The service in this city is terrible,”

they are making a hasty generalization. This judgment is based on a single instance, which is insufficient to accurately judge the overall quality of service across the entire city.

10. Red Herring

aka ignoratio elenchi, distraction-not on topic

A red herring is a logical fallacy that occurs when an irrelevant topic is introduced into an argument to divert attention from the original issue. The purpose of a red herring is to mislead or distract from the central point, effectively preventing a clear and focused discussion of the topic at hand. This technique can be particularly misleading because it shifts the debate to ground that is more favorable to the person using the fallacy.

For example, during a discussion about the effectiveness of environmental regulations, if someone suddenly shifts the conversation to the high salaries of CEOs in the oil industry, they are introducing a red herring. The new argument about CEO salaries, while possibly of interest, does not address the original question regarding the regulations’ effectiveness and serves only to distract from the substantive issues under discussion.

11. Appeal to Hypocrisy

An appeal to hypocrisy, also known as “tu quoque” (Latin for “you also”), is a logical fallacy that occurs when a person counters an argument by pointing out hypocrisy in the opponent’s position, rather than addressing the merits of the argument itself. This fallacy attempts to discredit the opponent’s argument by suggesting that their actions or words are inconsistent with the position they advocate, thereby implying that the argument is invalid.

For example, if someone argues that we should reduce our carbon footprint to combat climate change, and another person responds,

“But you drive a car and fly in airplanes all the time!”

they are committing an appeal to hypocrisy. This response doesn’t engage with the argument about reducing carbon footprints or the validity of combating climate change; instead, it attempts to discredit the speaker by highlighting a perceived inconsistency in their behavior. This fallacy deflects from the actual issue and does not provide a logical response to the argument presented.

Conclusion

Logical fallacies avoid discussing the issue directly usually because the person using the fallacy either does not know a valid argument, or they do not really wish to discuss it. People frequently do not wish to discuss issues they want to believe. Sometimes it’s easier to follow feelings or emotions.

The fact that someone uses a logical fallacy does not mean they’re wrong about the argument, it just means they have yet to make a valid argument. You can respond to logical fallacies by pointing them out and asking for another argument. Or, even better, if you know a valid argument that supports the other side, then point out the logical fallacy and give them the better argument and then discuss why you believe one valid argument over another. In essence, you hold a mini-debate with yourself.

For each issue that interests you, try to understand the valid arguments on both sides. When an issue has valid arguments on both sides, it’s good to know because going into a discussion, you already know where both sides will land and can better watch for logical fallacies.

1 thought on “Logical Fallacies Overview”

Hi Mike,

Just wanted you to know that I’ve linked to this topic on my blog: https://jesthinking.com/critical-thinking/

No back-link sought.