Are you curious about what religions were around in Colonial America? The focus of this article is on the more common religions represented in the New England area during the time of Roger Williams as documented in writings of the time, from 1631 through his death in 1683 and to the Founding Fathers about a century later. To be clear, there were literally hundreds of religions in America during this period of time. The 1784 book “An Alphabetical Compendium of the Various Sects” documents hundreds of Christian sects many of which had representations in America and was part of the research for this article.

Roger Williams proved the concept of modern American society by creating a multi-religion multicultural secular colony. With this overview, you will see that many religions were represented. Finally, I’ll touch on a few of the popular existing religions of today and how they fit in with America’s history.

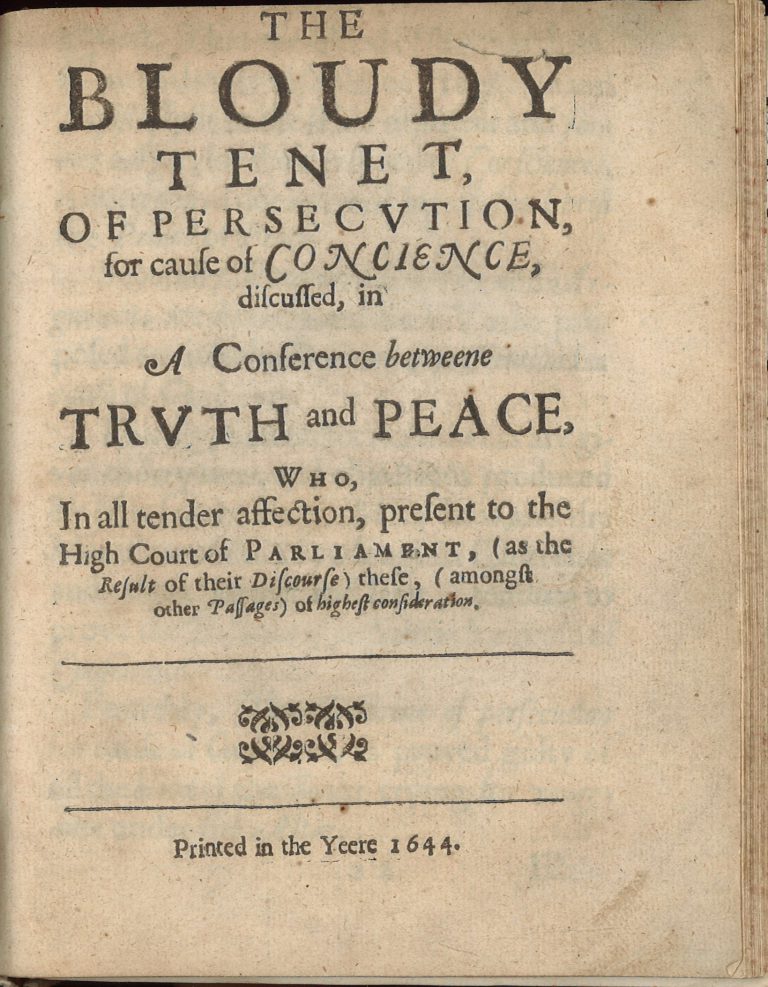

To set the stage, let’s start in 1655 when the Providence colony surprised the other colonies by welcoming Jewish settlers. Roger Williams visited them in Newport, and in response to the charge that he advocated infinite liberty of conscience, he wrote a famous letter. The story in the letter has become known as the Parable of the Ship and is used as an illustration of separation of church and state. Here is the relevant passage–edited for clarity:

“…There goes many a ship to sea, with many hundred souls in one ship, …and is a true picture…[of a] society. …papists and protestants, Jews and Turks, may be embarked in one ship; …All …I pleaded for… [were these] two hinges –

[FIRST] that none of the papists, protestants, Jews, or Turks, be forced to come to the ship’s prayers or worship, nor compelled from their own particular prayers or worship, if they practice any.

[SECOND] …the commander of this ship ought to command the ship’s course, …and also command that justice, peace, sobriety, be kept and practiced, both among the seamen and all the passengers. If any of the seamen refuse to perform their services, or passengers to pay their freight; if any refuse to help…towards the common …defense; if any refuse to obey the common laws …if any shall mutiny …if any should preach…that there ought to be no commanders or officers…the commander …may judge…and punish such transgressors…” –Roger Williams, 1655.

For more, read my 16-minute deep dive: The American Tradition of Separation of Church and State.

Before getting specific, let’s consider the “seekers,” emblematic of a significant attitude of spiritual inquiry that began permeating the colonies around the time of Roger Williams in the early 1630s.

Seekers

A seeker is someone who is unsure about their religion, opens their mind, and researches various religions using some merit system to determine which best fits their beliefs.

This culture of questioning traditional religious norms laid the groundwork for the First Great Awakening, a pivotal religious revival that swept through the colonies starting in the 1740s. This era was marked by a profound emphasis on personal faith, emotional religious experiences, and a broad questioning of established religious authority—themes that were foundational to the seekers’ attitudes and which would deeply influence the American religious landscape.

To be clear, there are types of Seekers. A Christian Seeker is someone who still believes in Christ, but is not sure the sect they currently belong to is correct. For example, some like the pomp and circumstance of the Roman Catholic church, and some do not. Roger Williams, for example, did not because he did not like the rituals.

The following quote from 1654 talks about Seekers.

“…Seekers, who deny the Churches and Ordinances of Christ.” –Ch. 5, Wonder-Working Providence, Johnson, 1654

Here is a footnote from the 1910 edition of the same book:

“The Seekers, with whom Roger Williams had become identified as early as 1638, were men who had come to doubt or to deny that there were, or had been since the apostles’ day, any true church, divine sacraments, or valid ordinances, and who waited for more light.” –Wonder-Working Providence, Johnson, 1654.

While we’re on the subject of seekers, it’s a good time to briefly explore the position of non-believers, including agnostics and atheists.

Agnostics and Atheists

In the colonial tapestry of belief and skepticism, agnostics and atheists occupied a unique, often precarious, niche. The tolerance for such positions varied widely across the colonies, influenced by the prevailing religious attitudes of each community. In more liberal environments, there was a degree of acceptance, or at least a grudging tolerance, rooted in the broader ethos of religious inquiry and freedom that figures like Roger Williams championed. His invocation of

“if they practice any”

in the Parable of the Ship underscores a foundational respect for individual conscience, including the right to doubt or disbelieve.

However, this tolerance did not universally protect non-believers from persecution. In times of religious fervor or social tension, atheists, agnostics, and secular believers could become scapegoats for societal ills, viewed with suspicion and, at times, targeted. The Salem witch trials, reflected the darker side of religious intolerance.

Williams’ philosophy suggested a radical idea for his time: that persuasion, not coercion, should guide conversations about belief. This principle laid early groundwork for the principles of religious freedom and pluralism that would become hallmarks of American society.

Imported Religions

The religious landscape of the American Colonies was significantly shaped by imported religions, with Roman Catholicism and the repercussions of the Protestant Reformation playing pivotal roles.

The Reformation, sparked by events such as King Henry VIII’s separation from the Roman Catholic Church in 1534, led to the creation of multiple Protestant denominations, including Lutheran, Reformed, Anabaptist, and Anglican branches. This period of religious upheaval, known as the Protestant Reformation, catalyzed the diversification of Christian practice, influencing the variety of religious expressions that found refuge in the colonies.

The Anglican Church, established as the Church of England with the King at its head, represents a direct outcome of these tumultuous times, evolving into a distinct form of Protestant faith. This era of transformation allowed for the emergence and settlement of groups like the Puritans, seeking religious freedom or reform away from established European churches.

This separation or protest is known as the Protestant Reformation. A few decades that gave birth to several branches of Protestant religions — notably Lutheran, Reformed, Anabaptist, and Anglican. Anglican is by definition the version of the Protestant religion practiced by the Church of England and it has evolved over time. This time period of great unrest in Christianity opened the door for Puritans. For example, the Parliament repealed the King’s act in 1555, and put it back in 1559.

Roman Catholic, Papist, Papacy, or Popery

From America’s earliest days, Catholics encountered deep-seated prejudice. The Puritans, who held sway in many colonies, showed scant tolerance even for fellow Protestants, sometimes resorting to violence against those who diverged from their strict religious views. Catholics, associated with terms like “Papist” and “Popery” that underscored foreign allegiance to the Papacy, found themselves particularly marginalized. By 1776, their numbers were modest, comprising roughly 1% of the population. It wasn’t until the 1840s, well after the era of the Founding Fathers, that Catholicism began to gain significant traction in America. This growth reflected broader changes in American society and religious tolerance. Today, Catholics represent about 22% of the U.S. population, illustrating a dramatic shift in religious demographics and acceptance over the centuries.

Roman Catholicism’s origin story starts in Rome, several centuries after Jesus’ time, with the formation of the Bible in the 4th century.

Roman Catholics ushered in the darkest time in mankind called the Middle Ages, formally the Dark Ages, from about 500 CE to 1,500 CE. Its introduction to North America occurred primarily through Spanish and French explorers and settlers before the Puritans’ arrival, seeking to establish a Christianity free from what they termed “popery.” This era, spanning roughly from the 15th to the 17th centuries, was characterized by the Catholic Church’s significant influence in shaping the new territories, alongside the Puritans’ quest for religious reform.

“…the Papist, who with (almost) equal blasphemy and pride prefer their own Merits and Works of Supererogation as equal with Christs unvaluable Death, and Sufferings.” –Ch. 5, Wonder-Working Providence, Johnson, 1654.

Roman Catholics were known as Papists during this time for their adherence to the Pope.

Maryland Catholics

Within this context of religious plurality and tension, Maryland’s early experiment in religious freedom stands out as a noteworthy contrast, especially concerning the Catholic presence in Colonial America. Despite Maryland’s foundation as a sanctuary for Catholics under the Calvert family, Catholics across the colonies, including Maryland, faced significant challenges. By the time of the American Revolution, they constituted a modest fraction of the population—less than 2%—reflecting the pervasive challenges they encountered in practicing their faith openly and participating fully in the colonial society. Furthermore, among the esteemed group known as the Founding Fathers, none were Catholic, underscoring the marginal position of Catholics in the political and social spheres of the time. This detail highlights the broader narrative of religious diversity and tension in Colonial America, illustrating how deeply religious affiliations were intertwined with identity, loyalty, and power, long before the significant demographic shifts of the 19th century would begin to alter the religious landscape of the nation.

Anglican Church of England

In the tapestry of Colonial America, the Anglican Church stood as a testament to the Protestant Reformation’s enduring impact, casting a long shadow over the New World’s religious landscape. Within this realm, a myriad of Protestant groups emerged, each carving out their own spiritual niche in the pursuit of purity and individual belief.

Puritans embarked on a fervent quest to “purify” the Church of England from the remnants of Roman Catholic practices, aspiring to a faith unadorned with the complexities of ritual and hierarchy. They weren’t alone in their spiritual journey; Separatists, including the storied Pilgrims aboard the Mayflower, sought not just reform but complete separation, yearning for a place where they could practice their faith unencumbered by the Church of England’s reach. Their survival through the brutal first year in a new world was a testament to their resilience and faith.

Within this religious ferment, several unique voices emerged, challenging the norms and broadening the spectrum of belief:

The Gortonists, followers of the enigmatic Samuel Gorton, embraced a radical theology. They saw Christ not merely as a figure of the past but as a living presence within each true believer, a notion that roiled the orthodox:

“…the Gortonists, who deny the Humanity of Christ, and most blasphemously and proudly profess themselves to be personally Christ.” –Ch. 5, Wonder-Working Providence, Johnson, 1654

The Familists leaned into the mystical, valuing personal revelations above the established canon, a belief that set them apart in a community grounded in Scripture:

“…the Familist, who depend upon rare Revelations, and forsake the sure revealed Word of Christ.” –Ch. 5, Wonder-Working Providence, Johnson, 1654

Antinomians stirred controversy by challenging the very fabric of moral law, arguing for a faith led by grace rather than adherence to a set of rules:

“…Antinomians, who deny the Moral Law to be the Rule of Christ.” –Ch. 5, Wonder-Working Providence, Johnson, 1654

Meanwhile, Anabaptists and Baptists advocated for a separation of church and state, a stance that questioned the prevailing norms of governance and spirituality:

“…Anabaptists, who deny Civil Government to be proved of Christ.” –Ch. 5, Wonder-Working Providence, Johnson, 1654

The Prelacy, with their unwavering belief in the church’s authority and hierarchy, stood in stark contrast to the burgeoning call for religious autonomy:

“…The Prelacy, who will have their own Injunctions submitted unto in the Churches of Christ.” –Ch. 5, Wonder-Working Providence, Johnson, 1654

As the colonies wrestled with these diverse and often conflicting beliefs, the stage was set for the Great Quaker Debates, a chapter in history that would further define the contours of religious freedom in the burgeoning nation. The tapestry of faith in Colonial America was rich and varied, a reflection of a people grappling with the divine in an untamed land.

Quakers

The Quakers, or the Religious Society of Friends, stood out for their distinctive practices and beliefs. Originating in England in the mid-17th century, the Quakers quickly established a foothold in the American colonies, particularly in Pennsylvania, founded by the Quaker William Penn as a haven for religious freedom.

The great Quaker debates of 1672, led by figures like Roger Williams, exemplify a pivotal moment in colonial religion. During this era, Quakers encountered significant opposition and persecution in both England and the American colonies for their radical stances: their refusal to participate in military service, their objection to paying tithes (a tenth of one’s income) to the state church, and their rejection of traditional forms of worship and social hierarchy. It was August 1672 when these tensions came to a head, notably in Rhode Island, a haven of religious freedom founded by Williams.

Williams, at the age of about 69 or 70, famously rowed alone, all night from Providence to Newport to debate the Quakers on August 9, 10, and 12, and again on the 17th in Providence. These debates were not secluded theological discussions but public events marked by external conflicts with colonial authorities and other religious factions, illustrating the contentious religious atmosphere of the time. Despite these challenges, the Quakers’ unwavering commitment to principles such as pacifism, equality, and the pursuit of a direct, personal experience of the divine stood in stark contrast to the prevailing religious norms and practices of the time.

This series of debates, and Roger Williams’ enthusiastic participation in them, underscored the complex tapestry of religious beliefs in colonial America. It highlighted not only the Quakers’ steadfast dedication to their principles but also the unique role Rhode Island played as a space for religious dialogue and tolerance amidst a landscape of persecution.

Judaism in Colonial America

In the evolving religious landscape of Colonial America, Judaism carved out a small but significant presence, exemplified by Roger Williams’ welcoming of Jewish settlers in Providence, Rhode Island. This early instance of religious tolerance highlighted the diverse fabric of belief systems taking root in the New World. Jewish communities, though few, contributed to the cultural and religious diversity of the colonies, establishing congregations and synagogues that would serve as foundations for future generations. Their resilience and commitment to maintaining their traditions played a crucial role in the tapestry of American religious life, underscoring the values of freedom and pluralism that the nation would come to hold dear.

Islam in Colonial America

While the presence of Islam in Colonial America was less visible compared to other religions, the spirit of inclusivity espoused by leaders like Roger Williams in his famous Parable of the Ship hinted at a broader understanding and acceptance of diverse faiths, including Muslims. Although direct references to Muslims (‘Turks’) were rare and often entangled with the period’s geopolitical views, the foundational ideals of religious freedom and tolerance laid down during the founding era provided a groundwork for the eventual recognition and integration of Islamic faith within the tapestry of American religious and cultural identity. The inclusive principles articulated by the Founding Fathers and early thinkers like Williams set the stage for a nation that would grow to embrace a wide range of beliefs, including those of Muslim Americans.

Native American Religions in the New England Area

The various tribes of the New England area during this time had a variety of beliefs. While groups of tribes frequently overlapped in their beliefs, each tribe also often adopted a specific tradition. For example, let’s take a closer look at two: the Wampanoag and the Narragansett tribes.

The Wampanoag people, known for their role in the First Thanksgiving narrative, practiced a spirituality deeply rooted in the natural world around them. Their belief system recognized a great spirit, known as Kiehtan, who was seen as the creator of all things and the source of all life. The Wampanoag also held a profound respect for the interconnectedness of all living beings, emphasizing the importance of balance and harmony with nature. Seasonal ceremonies were crucial for the Wampanoag, marking times of planting, harvest, and thanksgiving, which were celebrated through dance, song, and feasting.

In contrast, the Narragansett tribe, inhabiting areas around Rhode Island, also centered their spiritual practices on the natural world but had unique traditions. The Narragansett people placed a significant emphasis on the power of dreams as messages from the spiritual world. They believed that dreams could offer guidance, warnings, or insight into the future, playing a critical role in personal and community decisions. The Narragansett were known for their healing practices, with medicine men and women using herbal remedies, spiritual rituals, and the interpretation of dreams to treat ailments and maintain the well-being of their community.

Misc. Overview

Arrived Later

The following list of religions arrived in America after Roger Williams’ death in 1683. To be clear, these religions were likely around, but I have not run into them in the limited scan of early colonial history books, journals, and letters…yet.

- 1750, Confucianism: Origins start in China with Master Kong in about 500 BC. One can think of confucianism as a philosophy or a religion. It’s arrival in America was likely long before 1750 and likely influenced some of the founding fathers.

- 1790, Hinduism: Origins start in India and is the oldest existing religion with origins going back 5,000 years. It is commonly accepted that Hinduism arrived on the shores of America in the 1790s.

- 1820, Buddhism: Origins start in India with Prince Siddhartha in the sixth century B.C. It is commonly accepted that Buddhism arrived on the shores of America in the 1820s with Asian immigrants, with significant increase after 1849 with the CA Gold Rush.

- 1820, Taoism: Origins start in China back to shamanism and nature religion in China about 142 C.E. Like Buddhism, it likely landed in America in the 1820s.

- 1848, Catholicism’s Expansion: The conclusion of the U.S.-Mexican War in 1848 marked a pivotal moment in the growth of the Catholic population in the United States. Through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the U.S. acquired vast territories from Mexico, including present-day California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, regions with significant Catholic communities. This territorial expansion not only increased the landmass of the United States but also the percentage of Catholics within the national population, highlighting a period where the acquisition of Catholic lands contributed to the religious diversity of the nation.

Not Created Yet

Here is a list of various popular religions today, the earliest of which was created seven decades after Roger Williams’ death in 1683.

- 1738, Evangelicals (to America about 1890): Origins start with various methodists in 1738 including English Methodism, the Moravian Church (in particular Nicolaus Zinzendorf), and German Lutheran Pietism. The arrival of Evangelicals occurred about a century after the Founding Fathers passed.

- 1830, LDS: Origins start in New York with Joseph Smith in 1830 where he dictated the Book of Mormon from a set of golden plates buried near his home in upstate New York by an indigenous American prophet.

The mosaic of religious beliefs and practices that flourished in Colonial America, from the early embracement of Jews by Roger Williams to the implicit acknowledgment of a diverse spectrum of faiths, including Islam, underscores a foundational commitment to freedom of conscience and the separation of church and state. These principles, seeded in the earliest days of the nation, reflect a profound understanding of the importance of religious liberty, including none, as a cornerstone of a free and democratic society.