Traverse the Depths of Life: Unveiling the Layers of awareness.

To properly explore consciousness, we need a framework. As part of my personal worldview, I think of consciousness in a particular way. To write about it, I have to name it, so I’ve labelled it the Mindscape Framework. It defines verbiage and it abstracts complex scientific disciplines for use in discussing subjects like consciousness and identity. It also leverages the levels of the mind as explored in “30 Philosophers.” I also used this framework to build The Consciousness Evolution timeline.

If this is your thing, I think you’ll enjoy the following on consciousness. If not, feel free to just skim the major categories here to get a feel for the language needed to properly explore things like consciousness and identity. Then check out Consciousness: From the Soul to the Abyss.

Consciousness

At the core of this framework is a specific usable definition for consciousness. Simply put, consciousness is the experience of reality and is limited, or surfaced through, the cognitive ability of things. While the consciousness of a mouse, chimpanzee, or human are uniquely different, they all experience reality in their own way and that experience is their consciousness. Plants and simple animals without brains “experience” reality in their way, but that experience falls into either none or preconscious. Also, the specialness of a being’s consciousness, as in the existence of a soul or energy, is something this framework avoids as unknowable. You can still believe in a soul or energy and use this framework to explore the mind, identity, and consciousness. In 30:Philosophers, I introduced the Material-Spiritual Framework for exploring such things.

In a gesture towards Aristotle’s hierarchical classification of life, this framework adopts a similar approach but updates it to reflect modern understandings of consciousness across different life forms. He distinguished between plants, animals, and humans based on their life energy, he famously did not believe in souls.

In revising his classifications which focused on nutritive, sensitive, and rational, this framework refocuses these categories into “None,” “Preconscious,” “Simple,” and “Complex.” The aim is to reflect a more inclusive understanding of consciousness that spans not only the biological spectrum but also considers non-biological entities and their potential experiences. At least in a theoretical way, it makes room for discussing alien life, and even the consciousness of the supernatural. For exploring consciousness, this framework abstracts the spectrum to none, preconscious, simple, and complex.

None: This category encompasses entities that lack cognitive abilities or a mind. It focuses on the lack of a cognitive framework necessary to experience reality. Things like rocks, rivers, and hammers fall into this category.

Preconscious: Includes things that have rudimentary sensory processing but do not demonstrate the complex cognitive abilities associated with consciousness. This category acknowledges the basic level of interaction with the environment exhibited by plants, certain simple animals, and even certain machines, without implying the presence of consciousness as experienced by more cognitively complex things.

Simple Consciousness: Some degree of cognitive ability. In the animal kingdom, attributed to animals with a nervous system. It usually includes at least some sensory perception, and perhaps some degree of emotional responses. This category encompasses beings that can experience their environment and engage with it in meaningful ways, albeit without the depth of cognitive complexity seen in entities with complex consciousness. It covers a range of life forms from simpler invertebrates to lower vertebrates, marking the beginning of experiential life.

Complex Consciousness is reserved for entities with advanced cognitive abilities, including but not limited to self-awareness, sophisticated problem-solving, nuanced social interactions, and possibly symbolic thought or language use. This category includes humans, certain mammals, some birds, and potentially advanced artificial intelligences or hypothetical extraterrestrial life forms. Beings with complex consciousness are capable of reflecting on their existence, making complex decisions, and experiencing a broad spectrum of emotions and thoughts.

Animal Kingdom Examples

In the animal kingdom, we can explore the range of consciousness from fruit flies to chimpanzees. For simple consciousness, animals have some cognitive ability. Fruit flies, garden snails, and the common octopus all exhibit simple consciousness. Fruit Flies, for example, exhibit learning and memory capabilities but with limited cognitive complexity. Even Garden Snails are capable of navigating their environment and demonstrating basic learning behaviors. The Common Octopus demonstrates problem-solving and learning within its environmental context, indicative of simple consciousness.

For complex consciousness, self-awareness, emotional intelligence, and complex social structures are key. In addition to humans, dolphins, elephants and chimpanzees demonstrate complex consciousness. While humans clearly exhibit sophisticated cognitive abilities, self-awareness, language, and the capacity for abstract thinking, Dolphins too, are known for complex social structures, problem-solving abilities, and show indications of self-awareness. It’s common knowledge that Elephants have great memories, but they also show empathy, and complex social behaviors, suggesting a deep level of consciousness. Chimpanzees are even more clever. They use tools, engage in social learning, and show behaviors indicative of self-awareness and complex emotional states.

General Artificial Intelligence (AI) represents a fascinating, albeit currently theoretical, frontier in the exploration of consciousness. As a reminder, the definition of consciousness in this framework is not tied to the animal kingdom on Earth, it is tied to experiencing reality which is defined as cognitive ability with sensory input. With cognitive ability and sensory input, it is possible to interact with reality. Anything that has cognitive ability and can sense reality in any way has a form of consciousness. Humans have human consciousness, dogs have dog consciousness, and AI systems have AI consciousness. Without reproduction, each AI system is an island of consciousness.

In some ways, AI systems already have aspects of consciousness superior to human consciousness. This is not an unusual thing, after all birds fly, dolphins swim, and meerkats live in complex burrow systems. They all experience reality far differently than we do. Some animals even have better sensory input than us. For example, hammer head sharks can sense electricity, and dolphins navigate by sonar.

Many predict that AI systems will one day be able to match human consciousness. The hypothesis posits that a sufficiently advanced AI could exhibit characteristics traditionally associated with complex human consciousness, including self-awareness, the capacity for learning, and even the potential for experiencing emotions. This form of consciousness would be distinct from biological consciousness as we understand it, rooted not in organic processes but in artificial neural networks and algorithms. Such AI would not only process information and solve problems at levels exceeding human capabilities but also adapt to new challenges, generate original ideas, and potentially understand and regulate its emotional states.

Most of the rest of the following focuses on defining aspects of “experiencing” reality, our definition of consciousness. For this tour, we’ll focus on the animal kingdom on Earth. The first two elements of consciousness are the basic ones: cognitive ability and memory. They are a bit easier to define than say, what it means to feel sad.

Weekly Wisdom Builder

Got 4 minutes a week?

A new 4-minute thought-provoking session lands here every Sunday at 3PM, emailed on Mondays, and shared throughout the week.

Exactly what the world needs RIGHT NOW!

Cognitive Ability

Cognitive ability encompasses the mental capacities for processing information, problem-solving, understanding concepts, and making judgments. It’s a fundamental aspect of an entity’s interaction with its environment, influencing how it learns, remembers, and applies knowledge. For the animal kingdom on Earth, cognitive ability has two levels per being: species and the individual. Each species has a general range of capability, and an average. Each individual falls within that range, which is not unlike modern ideas about IQ. For exploring cognitive ability, this framework abstracts the spectrum to none, precognitive, simple, and complex.

None: This category refers to entities that exhibit no signs of information processing or decision-making that would suggest the presence of cognitive functions. It includes inanimate objects and simple biological entities that operate based on chemical or physical processes without the need for mental processing. Things like sand, clouds, and toasters have no cognitive ability.

Precognitive refers to life forms or systems that exhibit basic, non-cognitive responses to environmental stimuli. They can sense reality and respond to it. These responses are not the result of conscious thought or decision-making but rather instinctual or automatic reactions that can be seen as precursors to more complex cognitive abilities. Precognitive abilities are typically found in life forms without a central nervous system or brain, relying instead on simple, decentralized mechanisms for interacting with their environment.

Simple Cognitive Ability denotes the presence of a mind capable of processing simple information about reality. In the animal kingdom, this level of cognitive function is associated with the presence of a brain and a nervous system. Cognitive abilities allow for adaptive behavior, learning, and at least short-term memory.

Complex Cognitive Ability denotes the presence of a mind capable of processing information, learning from experiences, making decisions, and solving problems. In the animal kingdom, this level of cognitive function is associated with the presence of an advanced brain and a nervous system capable of supporting complex mental activities. This includes adaptive behavior, learning, long-term memory, and at least simple problem-solving and social interactions.

Animal and Plant Examples

With animals and plants, we can explore the range of cognitive ability on Earth. From moving plants to octopuses, cognitive ability maps to consciousness pretty well. For precognitive abilities, beings have something like cognitive ability. Interesting examples of precognitive life on Earth includes the Venus Flytrap, bacteria, and fungi. The Venus Flytrap in a way eats flies. It responds to touch by closing its leaves, an automatic response without central cognitive processing. Some Bacteria exhibit chemotaxis, moving towards or away from chemical stimuli, a basic form of environmental interaction without cognition. Finally, Fungi communicate and distribute nutrients through a network, responding to environmental changes in a decentralized, non-cognitive manner.

Many lower animals exhibit simple cognitive abilities. For example, earthworms, goldfish, and frogs. Earthworms exhibit responses to light, moisture, and touch, indicating basic information processing and learning capabilities. Goldfish are known to remember feeding times and navigate mazes, showing evidence of learning and memory. Finally, frogs use their senses to hunt and avoid predators, exhibiting basic cognitive abilities for survival.

While humans represent the animals with the highest level of cognitive ability on Earth, chimpanzees in the primate line, and other animals also exhibit complex cognitive ability. This includes dolphins, crows, and the elusive octopus. Although Dolphins live in a watery world, they are known for their sophisticated social structures and problem-solving skills. Crows and humans branched from each other more than 200 million years ago, yet both lines ended up with brains with complex cognitive abilities. They demonstrate tool use, problem-solving, and complex social behaviors, indicating advanced cognitive functions. Octopuses branched more than 500 million years ago, yet they too evolved a brain with complex cognitive abilities, but as you see later, they did not evolve in other ways. They can solve intricate problems and use tools, showcasing advanced cognitive abilities and learning.

Returning to AI Systems, they demonstrate the ability to learn from vast amounts of data, solve complex problems, make decisions, and, in some cases, interact socially with humans. Whether this behavior mimics or is the same as humans or other animals is a philosophical question worth exploring. It’s also the same question we frequently ask in philosophy. For example, my dog Cola seemed to ask me for help. Just before my dog Cola passed, I would put treats on our coffee table. When she would accidentally knock them back, she would look up at me, seemingly asking for help. At times she seemed thankful, happy to see me, sometimes mad too. But was she asking for help? Or just mimicking past behavior that gave it the needed result? What is the difference between doggie thankfulness and human thankfulness? Is one better than the other?

Memory

Labeling the spectrum of memory capabilities from simplest to most complex is a useful way to conceptualize the evolution and diversity of memory across different life forms, including the stages of memory development within humans. For exploring memory, this framework abstracts the spectrum to none, pre-brain, short-term, long-term, and eidetic.

None: Refers to life forms that do not have any capacity for memory because they lack a nervous system or any mecha

nism for information storage and recall. This would apply to very simple organisms like viruses, plants, and fungi. While viruses rely on chemical interactions to invade host cells, plants grow and sometimes move, and fungi react through chemical responses, none have memory.

Pre-brain Memory: Could be applied to organisms that have basic nervous systems or nerve nets but lack a centralized brain.

Short-term Memory: Refers to the ability to store information over short periods, from seconds to days, but not months. This type of memory involves the temporary storage of information for immediate use and processing, which is essential for problem-solving, decision-making, and navigation.

Long-term Memory: Refers to the ability to store information over extended periods, from months to a lifetime. Long-term memory allows for the retention of learned skills, experiences, and knowledge. It is crucial for recognizing individuals, remembering past events, and learning from experience.

Eidetic Memory: This is a special case of memory, often termed “photographic memory,” characterized by the ability to recall images, sounds, or objects with high precision and detail for many years.

Memory in the Animal Kingdom

In the animal kingdom, we can explore the range of memory abilities from jellyfish to humans with a photographic memory. Pre-brain memory is an interesting category. These creatures, like certain jellyfish and sea anemones, exhibit simple learning behaviors or adaptations based on previous stimuli, suggesting a rudimentary form of memory not based on a centralized processing organ.

In contrast, short-term memory requires a brain. It is found in a wide range of animals with more developed nervous systems, including crickets, Sea Slugs, and Zebrafish. Crickets use short-term memory in mating behaviors and predator avoidance, reacting to immediate stimuli but with less evidence for the retention of these memories over long periods. Sea Slugs, a model organism for studying the neural basis of learning and memory, demonstrates simple forms of short-term memory like habituation and sensitization, without the complex neural structures associated with long-term memory in higher animals. Finally, Zebrafish utilized in studies of learning and memory, show the ability to learn and remember tasks over short periods. While they do have the capability for longer-term memory up to days, perhaps weeks, the focus often is on their rapid learning and short-term memory use in experimental settings.

For long-term memory, elephants have long been hailed as a prime example. While Elephants are the obvious candidate, crows and parrots also have this ability. Crows demonstrate long-term memory in tool use, food storage, and recognizing human faces. And Parrots can remember sounds, words, and tasks for years, demonstrating complex long-term memory. Perhaps the next you want to say, “you have a memory like an elephant,” perhaps switch it up to, “you have a memory like a crow!”

Although scientists are still trying to determine if eidetic memory exists, some individuals do appear to exhibit it. They can recall great details with high accuracy after many years. While rare among humans and not universally accepted as existing, the concept of eidetic memory represents the upper end of memory capability in terms of detail and fidelity of recall. While not an animal, AI is another example of this category of memory.

Next, let’s take a look at two traits more closely linked to the core of the debate surrounding consciousness: sentience and self-awareness. What does it mean to be sad? Some creatures are self-aware, but if Buddhism and others are correct, and there is no “self,” is this really a requirement of consciousness? First up, a survey of emotions in the animal kingdom.

Sentience

Sentience is the innate ability to feel various emotions. To represent the range, this framework abstracts the spectrum to none, presentient, simple, and complex. While simple sentience allows for immediate pain, hungre, and the like, complex sentients extends to more complex innate emotions. It’s important to note that sentience is not emotional intelligence, see below. While both rely on innate abilities, emotional intelligence is not solely innate.

None: Refers to life forms that do not have any capacity for emotions. They react to their environment in purely instinctual or reflexive ways. This includes bacteria, sea sponges, and corals.

Presentient: Presentient abilities are the ability to process pre-emotions. While lower animals, which evolved first, might react to stimuli, they do not have sentience. Let’s call that presentient as in the thing that evolved into sentience. These entities demonstrate basic responses to stimuli that could be precursors to emotions, but without the capacity for experiencing emotions as understood in sentient beings.

Simple Sentience: These animals do not suffer nor feel pleasure nor pain except in the simplest way. They might experience basic forms of emotions or emotional-like states, albeit in a manner not fully understood or as complex as higher animals. They might feel something, but it’s unclear what they feel.

Complex Sentience within the animal kingdom is a spectrum of abilities that experience suffering as well as the dichotomy of pleasure and pain. These species have a wide range of emotions, clearly experiencing both suffering and pleasure, indicative of complex emotional lives.

The Emotions of Life on Earth

We can explore and discuss a range of emotions and emotion-like traits from moving plants to sensitive pigs. For emotion-like presentient life, let’s look at the Mimosa and earthworms. The Mimosa plant reacts to touch by folding leaves, a simple protective mechanism rather than an emotional response but akin to something like proto fear. Earthworms respond to physical stimuli like light and touch without indicating any form of emotional processing.

For examples of simple sentience, take honeybees, crabs, and octopuses. Honeybees display behaviors that could indicate stress responses and simple communication of states akin to emotions. Crabs react to harmful stimuli in ways that might sugge

st discomfort or stress. Octopuses show behaviors suggesting frustration, curiosity, and problem-solving, indicating a form of basic emotional processing.

For human-like complex sentience, take cows, pigs, and elephants. While Cows demonstrate emotions such as excitement, fear, and social stress, Pigs are known for their intelligence and emotional complexity, showing signs of joy, sadness, and distress. Elephants exhibit mourning, joy, and complex social bonds, indicating a deep emotional capacity.

Self-Awareness

Self-awareness is the intricate understanding that one exists as an individual, separate from the environment and other entities. It’s a cognitive milestone that underpins complex social interactions, problem-solving, and the development of emotional and transcendental intelligence (EI and TI). While human-like self-recognition is documented in great apes, elephants, and dolphins, intriguing manifestations of self-awareness are also observed in some bird species, such as magpies. The recognition of oneself not only augments problem-solving abilities but also enriches social dynamics, making self-awareness a cornerstone for both EI and TI. For exploring self-awareness, this framework abstracts the spectrum to none, semi, and fully.

None: These entities do not exhibit a discernible sense of self. Their behaviors are driven by instinct and learned responses without any indication of self-recognition or introspection.

Semi Self-Aware: Animals within this category display behaviors suggesting a basic sense of individuality and may exhibit complex social behaviors or problem-solving skills indicating a rudimentary self-awareness. However, they generally do not recognize themselves in mirrors or fail to do so consistently. Certain bird species that engage in sophisticated social behaviors and some mammals that show an awareness of their actions and effects on their surroundings but do not pass traditional mirror tests might be placed here. This highlights the existence of self-awareness beyond the confines of the mirror test, embracing a broader spectrum of cognitive expressions.

Fully Self-Aware: This category is reserved for animals that consistently demonstrate self-recognition in mirrors, or the equivalent. It suggests a developed and conscious sense of self. This advanced level of self-awareness supports complex problem-solving, fosters empathy, and enables nuanced social interactions, reflecting a profound cognitive capability.

Self-Awareness in the Animal Kingdom

While it’s pretty clear that most insects, fish, and reptiles are not self-aware, the complexity of the idea of “self” warrants a cautious approach to such classifications.

For sure, some animals are “semi” aware. Rats, Squirrel Monkeys, and cats are interesting examples of semi self-aware animals. Rats can demonstrate empathy and complex problem-solving, indicating rudimentary self-awareness. Also, Squirrel Monkeys engage in complex social interactions and learning that hint at self-awareness. A clearer example is cats. While results vary widely, even with the same cats, they do sometimes recognize themselves in a mirror, and usually respond strongly to images of cats on a flat screen.

Members of the fully self-aware group include such animals as the great apes (such as chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans), elephants, dolphins, and certain birds like magpies. Magpies not only exhibit clear self-recognition but also leverage this awareness in navigating their social and environmental landscapes.

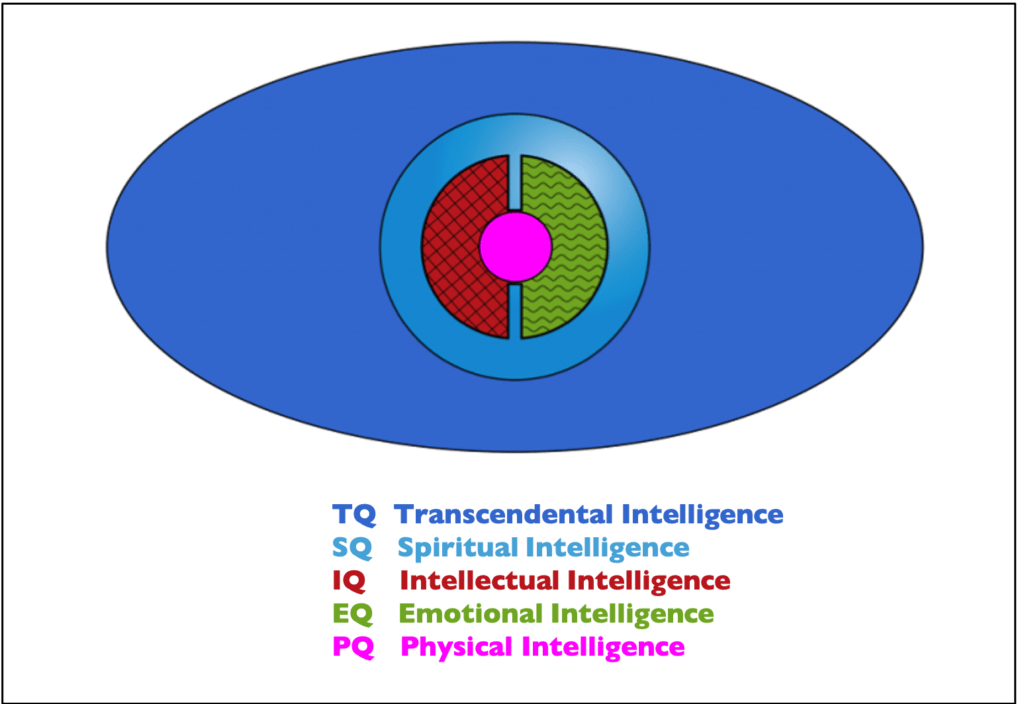

The final three traits before we dive into a case study explore what it means to be intelligent. It breaks down intelligence into “general” intelligence, emotional intelligence, and transcendental intelligence.

Intelligence

Intelligence is the measure of an entity’s capacity to engage in abstract thinking, problem-solving, learning from experiences, adapting to new situations, and employing reasoning to navigate challenges. It reflects how individuals or species interact with their environment and each other in cognitively complex ways. For exploring intelligence, this framework abstracts the spectrum to none, simple, intermediate, and complex.

None: This category is reserved for organisms that exhibit no discernible problem-solving or learning abilities beyond instinctual behaviors. Their interactions with the environment are largely reactive and do not demonstrate the capacity for adaptation or learning that characterizes intelligent behavior. Many simple organisms, such as certain invertebrates, including jellyfish, fall into this category.

Simple Intelligence: Entities exhibiting simple intelligence demonstrate basic problem-solving skills, can learn from direct experience, and adapt their behaviors in response to immediate environmental challenges. This level of intelligence is evident in many animals and is characterized by the ability to solve straightforward problems, learn simple tasks, and modify behavior based on past outcomes.

Intermediate Intelligence: Adds proto cultural transmission abilities and includes some basic problem-solving skills. Animals with intermediate intelligence can engage in basic social interactions, and might exhibit proto self-awareness, but do not use tools effectively, nor plan for future events beyond immediate needs. They can navigate simple problems, learn basic tasks, and sometimes manipulate their environment in basic ways.

Complex Intelligence: Adds clear cultural transmission abilities and encompasses advanced problem-solving skills, learning, adaptability, and understanding of abstract concepts. Cultural transmission involves the passing down of concrete skills, behaviors, and knowledge that directly enhance survival and adaptation, such as tool use or food gathering techniques. Animals with complex intelligence can engage in sophisticated social interactions, use tools creatively, plan for future events, and exhibit self-awareness.

This level of intelligence is most commonly associated with mammals and birds, such as primates, cetaceans, elephants, and corvids, but also notably includes octopuses, showcasing convergent evolution. These species can navigate intricate problems, learn complex tasks, make decisions based on reasoning, and often manipulate their environment in innovative ways.

The Intelligent Animal Kingdom

For a range of simple to complex intelligence in the animal kingdom, we can explore the range of animals with brains from the Nautilus to the common octopus. For simple intelligence, the Nautilus, a cephalopod, stands out. Cephalopods branched very early in the evolutionary tree, about 485 million years ago. Nautiluses display basic problem-solving capabilities reflective of their simpler nervous systems. Unlike their more complex relatives, nautiluses have not demonstrated the advanced learning and adaptability seen in octopuses or cuttlefish, highlighting the diversity and evolutionary variance of intelligence within cephalopods.

For intermediate intelligence, let’s focus on dogs, parrots, and horses. Dogs exhibit learning from humans and other dogs, understanding commands, social hierarchies, and showing basic problem-solving. Their behaviors, such as begging or understanding human gestures, indicate a level of social learning and adaptability. Parrots can learn complex vocal patterns, understand concepts like quantity and color, and solve puzzles, indicating more than simple intelligence. Finally, Horses exhibit social learning, understanding human cues, and remembering complex paths, showcasing their intermediate cognitive abilities.

For complex intelligence, let’s focus on crows and return to the ancient cephalopod class of animals. Crows and ravens use tools creatively, solve complex problems, and understand abstract concepts like zero and causality. They learn from each other, craft and use tools in specific ways that are passed down through generations. They also adapt their behaviors based on human activities, a learning process that involves observation and imitation. Octopuses exhibit remarkable problem-solving abilities. Although chimpanzees and octopuses inhabit vastly different environments and stem from some of the earliest branches of evolutionary development, octopuses might come close to the intelligence of a chimpanzee, at least in their own unique way. Octopuses solve intricate problems, use tools, and exhibit behaviors suggesting planning and complex decision-making. Octopuses stand out as a remarkable example of Complex Intelligence. Their intelligence evolved independently from vertebrates, providing a fascinating case of convergent evolution. While we don’t think they suffer and experience the dichotomy of pleasure and pain beyond simple sentience, there is no doubt about their intelligence. While octopuses are generally solitary animals, making the concept of cultural transmission as seen in social animals less applicable, they have shown they can learn to solve problems by watching other octopuses, suggesting a basic form of social learning.

Emotional Intelligence (EI)

Emotional Intelligence (EI) involves the innate ability to recognize, understand, manage and reason with emotions, both in themselves and others. It underpins the ability to engage in sophisticated social interactions, make decisions influenced by emotional and moral considerations, and adapt behaviors based on an understanding of the emotional landscape of social groups. While sentience relies solely on innate abilities, EI relies on a build up of knowledge. Like all knowledge, EI is learned through a buildup of impressions from birth. For exploring emotional intelligence, this framework abstracts the spectrum to none, simple, intermediate, and complex.

None: This category applies to life forms that show no observable evidence of recognizing emotions in themselves or others, nor do they modify their behavior based on emotional cues. This might include many simpler forms of life, such as most invertebrates, where behavior appears primarily driven by instinctual processes rather than emotional cognition.

Simple EI: Non-symbolic intelligence in animals that exhibit simple emotional intelligence usually starting with social signaling and extending to very basic forms of empathy, and emotion-based learning. They can recognize emotional states in others and respond in ways that suggest a rudimentary understanding of those states, although their responses might be limited to specific contexts or less varied than those seen in animals with complex EI. Examples could include some mammals and birds that show basic empathy or emotional contagion, such as comforting behaviors or collective mood responses.

Intermediate EI: Characterized by a wide range of emotionally driven behaviors and social skills, including simple or proto empathy, simple or proto moral reasoning, and simply or proto symbolic thought. Animals with intermediate EI will manipulate based on emotional understanding and participate in more sophisticated social bonds. They can make decisions that reflect an understanding of the emotional and moral implications of their actions, engaging in behaviors that suggest some level of social and emotional awareness.

Complex EI: Complex emotional intelligence introduces the idea of true symbolic thought and is characterized by a wide range of emotionally driven behaviors and social skills, including deep empathy, moral reasoning, manipulation based on emotional understanding, and the ability to maintain sophisticated social bonds. Animals with complex EI can make decisions that reflect an understanding of the emotional and moral implications of their actions, engaging in behaviors that suggest a high level of social and emotional awareness. While knowledge of death usually requires a TI level of intelligence to convince a population, individuals with complex EI frequently demonstrate at least a basic understanding of death.

EI in the Animal Kingdom

For a range of simple to complex emotional intelligence in the animal kingdom, we can explore the range of animals from rats to dolphins. For simple EI, take rats, pigeons, and dogs. Rats show distress when other rats are in discomfort, indicating basic empathy. Pigeons have been observed to react differently to humans displaying different emotions, hinting at a basic understanding of emotional states. Dogs display a range of emotions and can recognize and respond to human emotional states, although their understanding and response might be considered more developed, potentially straddling simple and intermediate categories.

For intermediate EI, squirrels and pigs demonstrate intermediate EI well. Squirrels use deception in hiding nuts, showing a basic form of manipulation based on understanding the intentions of others. Finally, Pigs are capable of complex social interactions an

d show signs of distress, joy, and empathy within their social groups.

For complex EI, in addition to humans, other animals exhibit it. For example, we see advanced EI in dolphins, elephants, and primates from orangutans to chimpanzees. Dolphins exhibit sophisticated social behaviors, self-awareness, and have been observed to exhibit behaviors suggesting deep emotional intelligence, such as consolation and cooperation. Elephants known for complex social behaviors and mourning rituals, suggesting proto empathetic understanding and social bonds. Some might categorize them on the edge of complex EI. Orangutans display complex emotional responses, can learn sign language to communicate abstract concepts, and show advanced problem-solving abilities. Chimpanzees demonstrate a variety of complex emotional behaviors including empathy, manipulation, and an understanding of fairness and justice.

Transcendental Intelligence

Transcendental Intelligence (TI) is the ability to rise intellectually above the self and store knowledge outside the body. It involves the capacity to engage with and create abstract concepts, such as art or rituals, that do not have direct practical utility but serve to enrich the intellectual and emotional life of individuals and the group. This form of intelligence reflects an understanding and creation of meaning that transcends the tangible and immediate, involving aesthetic appreciation, symbolism, and possibly the beginnings of what could be considered spiritual or philosophical contemplation. It surfaces in acts like the creation of art, participation in sophisticated communication, profound knowledge gathering, and active participation in cultural transmission, especially over multiple disparate generations.

Humans possess TI especially in the form of advanced cultural transmission and in particularly in language, oral traditions, books, libraries, and videos. Without actually ever going to Africa and experiencing it directly, humans can read a book or watch a documentary about it. Those impressions, just like our memories, are not the real thing, but do facilitate understanding.

Modern AI systems do not since they cannot reproduce nor freely interact with other AI systems. While humans also possess EI, the question of whether AI can learn to suffer and experience pleasure and pain is an open question.

Current AI computers for sure possess, or can possess, TI. They are very intelligent and do possess some form of sentience and self-awareness even if just mechanical in nature. The big question in AI is are they, or can they become, emotionally intelligent? This involves exploring the nature of their sentience and how it is different from animal sentience. Can an AI computer truly suffer? And if not, can we add true sentience?

Meanwhile, humans are emotionally intelligent beings, which means our consciousness is sentient, self-aware, and emotionally intelligent. But are we the top of the chain? Are their aliens out there that have more cognitive abilities, including more sentience, self-awareness, and intelligence? If so, does that make them “more conscious” than humans? Also, what if there is something beyond our consciousness, on the level of sentience, that exists but we’re missing it? Some aspects of super consciousness we can’t even fathom? Finally, many think of Gods as sentient-self-aware-intelligent-supernatural beings that are better than us. But what does “supernatural” mean? Assuming for a moment that supernatural beings like gods, angels, and demons exist, let’s conclude with a speculation. Like the magic of a magician, does supernatural simply mean we don’t understand it?

Case Study: Levels of a TI Mind

While it is difficult for humans to explore the idea of beings smarter than us, we can explore our minds deeply. The human mind is an interesting case study in consciousness. In “30 Philosophers,” which focuses on the modern human mind, I defined “Levels of the Mind” to explore the intricacies of cognitive processing more deeply. The following is an introductory version of the exploration of consciousness, including memory and levels of the mind, explored throughout “30 Philosophers.” I classified the levels of the mind as three main levels that handle most of consciousness and mentioned a forth.

Levels of the Human Mind:

- Preconscious Level: Situated at the threshold of our awareness, your preconscious houses easily accessible information and recent experiences. This level acts as a gateway between the immediate recall required in daily tasks and the more profound, often elusive memories stored deeper within our minds.

- Conscious Level: Here, memory is actively engaged by your conscious mind. It encompasses the short-term and working memory that we use to process and respond to our environment in real-time. This level is where sensory input becomes cognition, enabling us to navigate the present moment with awareness and intention.

- Deep Subconscious Level: Beyond the immediate reach of your conscious mind lies the deep subconscious, a reservoir of long-term memories, forgotten or suppressed experiences, and the underlying patterns that shape our perceptions and behavior. This level holds the essence of our learned knowledge, skills, and deeply ingrained beliefs, accessible through focused introspection or triggered by specific stimuli.

- Unconscious Level: Although not the primary focus of this exploration, unconscious memory governs automatic processes and reflexive actions, such as the heartbeat or instinctual responses, underscoring the foundational role of memory in our biological survival and function.

These abstracted levels of the mind can facilitate exploration of consciousness.

From the Book

To conclude this framework, let’s transition from the more formal tone used to this point to a more descriptive exploration. This section will focus on the ideas about the “Levels of the Mind” in “30 Philosophers.” What follows offers a deeper exploration into the intricacies of cognitive processing in humans. The following is a shorter introductory version of the exploration of consciousness explored throughout “30 Philosophers.”

Understanding human memory and cognition is a journey through the complex landscapes of the brain’s capabilities, ranging from the sheer capacity for information storage to the nuanced processes that govern our conscious and subconscious thoughts. In traditional cognitive science, memory is often segmented into various types—short-term, long-term, and sensory memory—each playing distinct roles in how we store, access, and utilize information. This approach offers a foundational understanding of memory’s role in human intelligence, learning, and behavior, highlighting the remarkable capacity of the human mind to retain and recall vast amounts of information.

“Levels of the Mind” delves into the realms beyond mere data storage and retrieval, inviting us to consider how our minds navigate the complex interplay between accessible knowledge, hidden memories, and the very essence of our identity and awareness. By distinguishing between the preconscious—home to easily retrievable facts and recent memories—and the deep subconscious, where our most elusive thoughts and memories reside, the framework adds depth to our comprehension of memory’s role in shaping our perceptions, decisions, and interactions with the world.

The framework in the book proposes a nuanced categorization of the mind’s operations, dividing it into the conscious, preconscious, and deep subconscious levels, alongside the unconscious dimension controlling automatic processes. Such a perspective enriches our understanding of memory by framing it within a broader context of cognitive and emotional experiences.

Experiencing the “Now”

Your preconscious, your accessible library, catalogs both current impressions and memories of past impressions. That phrase, “memories of past impressions,” is very critical and what the book talks about when it explores recoloring memories. You, the sense of “self,” is a series of streaming impressions stored as memories.

Your active focus is a dance among your senses, conscious and preconscious, oscillating between this moment and the reservoir of easily retrievable information, all colored by your deep subconscious. When you feel gravity pressing on your feet or buttocks or the tactile feeling of your clothing, that’s you bringing a current “live” impression from your preconscious to conscious. When you retrieve a memory, you bring it to your conscious mind creating a new impression of an old memory. These impressions are evaluated for relevance and either fade away or sink into your subconscious.

As you move through the material world, you experience impressions which form your present moment, your idea of “now.” Essentially, new impressions merge into your current awareness, which is a combination of sensory input, feelings, and thoughts. Generally, you have a primary focus and you’re aware of a main expectation, such as “I need to get up for work,” but you might also have a primary focus like “What time is it?” While you are focusing on something and dealing with a main expectation, your brain is also bustling with preconscious expectations. For instance, when you wake up and step onto the floor, your brain expects the floor to provide support. If the floor is there, it will use it and not bother you. If the floor is gone, with startling fear, it will interrupt you and let you know.

Note on the Buddhist concept of self, of atman, or better said: “non-self.” In delving into the Buddhist concept of self, particularly the doctrine of “non-self” or anatta, is it what we call the present moment? The formation of the idea of “now.” These profound questions about the nature of existence and consciousness have been asked for at least thousands of years. Is the “you” we speak of—the entity believed to be making choices—truly an autonomous agent, or is it a manifestation of deeper, deterministic forces? Buddhism challenges the notion of a permanent, unchanging self (atman) by suggesting that what we consider to be the self is in fact an aggregation of transient states and processes, devoid of inherent essence. This perspective prompts us to reconsider where self and free will reside, if at all, and how these concepts interact with the domains of biology, psychology, and spirituality. By questioning the existence of an independent “self” and exploring the idea that our perceived agency might be an illusion, we delve into the intricate relationship between consciousness and identity. This exploration takes us to the heart of our inquiry into consciousness, urging us to examine the very foundations of who we believe ourselves to be, how we make choices, and the interplay between our biological nature and our deepest spiritual understandings.

Ok, back to exploring the present moment.

As part of experiencing “now,” your mind prioritizes current sensory input, emotional states, and memories. At the same time, you, whatever that entails, are choosing what to focus on. This focus has an immediate impact on your “now,” but it also leaves a lasting impression that your mind categorizes, prioritizes, and stores as a memory, and it includes feelings, imagery, and both prelinguistic and linguistic thoughts.

The choices you make in the “now,” shape your future, which influences the selection and ranking of memories. If you focus on sad things, you will “color” your current impressions sad, and that not only affects you now, but in the future. That’s why “fake it, until you make it,” frequently works. It’s also why they say that if you want to form a new habit, do it daily for 30 days. This is also why Stoic principles, modern therapy, and other practices work too. You essentially massage the “now,” to affect the future.

In neuroscience this is called your “salience network.” It identifies what’s important among the myriad of impressions we experience, helping to bring various “live impressions” and “memories” into the “spotlight” of our consciousness. It decides using factors like emotional weight, urgency, familiarity, and social constructs.

The “familiarity” factor is why “30 Philosophers” explored the familiarity cognitive bias in Chapter 14. The impact of “norms” factor is why it explored the concept of “normal” in Chapter 5 on Confucius, and why so much time was spent understanding social constructs and your worldview. In chapters 30 and 31, the book explores Nihilism and Existentialism which annihilate these “norms” and introduce the idea of building your authentic self.

Experiencing Ideas

Now, the book presents my Idea of Ideas and it’s about here in the book that I explore where an “idea” fits in with all this. Here is the final bit of the descriptive text concluding this framework.

Now, the book presents my Idea of Ideas and it’s about here in the book that I explore where an “idea” fits in with all this. Here is the final bit of the descriptive text concluding this framework.

Consider that every “idea” starts as an impression, a simple sensory response or feedback. This experiencing of reality is what builds each person. Starting at birth with a blank slate, your mind has “potential intellect,” as introduced and explored with Al-Farabi in Chapter 16. It’s the idea that life is about experiences. As you move through life, impressions accumulate. After a time, the impressions start melding with pre-existing knowledge, beliefs, and other impressions, gradually evolving into more refined and interconnected ideas.

Much like the fleeting impressions you experience, an idea fits within your stream of consciousness as one of the many mental constructs that you can choose to focus on. It’s an impression that has been elevated in significance or intricacy, one that you can easily recall from your preconscious or, with a bit of effort, from your deep subconscious. From there it might sink into the depths of your deep subconscious, or fade away, no longer part of you.

For example, as you walk, you can remember your last few steps, but the rest fade away. That seems right, you don’t really need to remember every step. Now consider something more important, someone tells you their phone number, you memorize it; it’s now part of you. A phone number you can recall with ease, so it’s part of your preconscious. Over time, it settles into your deep subconscious, you can recall it, but you have to “think about it.” This idea of a specific phone number can reside in your deep subconscious, but over time, it can also fade away, no longer a part of you. Or you can write it down in an address book so you can retrieve it later. This is why Albert Einstein famously remarked that he didn’t bother memorizing his own phone number because he could simply look it up. This is also why above, I said that your deep subconscious also includes external ideas. These external sources are varied but include other people, books, and the internet.

Whether you’re contemplating the nature of the divinity, wondering about the properties of a magical wand in a book you’re reading, or considering the implications of a scientific theory, they are “ideas.” And all ideas, just like impressions, are subject to your prioritization and focus. They play a critical role in shaping your perception of the “now” and they influence your future.

This transition from traditional concepts of memory capacity to the layered approach outlined in “30 Philosophers” not only broadens our conceptual toolkit but also connects the dots between empirical findings in neuroscience and the philosophical inquiries into the nature of consciousness and self. It challenges us to consider not just what we remember, but how the act of remembering—and the layers of cognition that facilitate it—influence who we are, how we think, and how we experience the “now.”

In essence, while cognitive science provides the structure and mechanics of memory, “Levels of the Mind” enriches this understanding with a philosophical exploration of the mind’s deeper, more subjective dimensions. This integrated approach opens new avenues for appreciating the complexity of human cognition, offering insights into the profound mysteries of memory, consciousness, and the human experience.

— map / TST —

Further Reading:

- Consciousness: From the Soul to the Abyss – A descriptive exploration of consciousness.