Abstract: This article reimagines ancient hominin populations at significant prehistoric junctures—300,000 and 700,000 years ago. Traditional scholarship often limits these populations to several hundred thousand individuals. Challenging this conventional view, this article proposes a dramatically higher count, speculating that as many as 2 million hominins may have roamed the Earth 700,000 years ago, with numbers potentially exceeding 3 million by 300,000 years ago. By reevaluating ecological and archaeological data, this article aims to illuminate the possible scales of early hominin societies and their extensive ecological impacts, offering a fresh new look at the complex narrative of human ancestry. The goal is to open minds to these possibilities as archaeologists and paleontologists continue to uncover the past. At this critical juncture of discovery, the buildup of new information over the next few decades will either lend credence to such speculations or reaffirm traditional views.

Beyond Boundaries: Tracing the Broad Ecological Footprint of Early Hominins Across Time.

Embarking on a speculative journey through time, this article seeks to take a new look at the numbers that might have defined ancient hominin populations at two pivotal moments in prehistoric times. In essence, we are conducting a speculative “census”—two, in fact—one for 700,000 BCE and another for 300,000 BCE. We use the term “census” metaphorically to describe our efforts to reconstruct the population sizes of these ancient hominins. While no actual census data exist for these epochs, we draw upon rational ideas about the available empirical evidence to estimate these populations.

Why not stick with the available empirical studies? While empirical studies provide invaluable insights and are grounded in rigorous scientific methodologies, they often focus heavily on Homo sapiens and their direct lineages, sometimes at the expense of a fuller understanding of other hominins. These studies can also impart a narrative of inevitable human dominance, suggesting a linear progression towards modern humans as the ultimate evolutionary outcome. Our approach seeks to broaden this perspective by considering a wider array of possibilities and scenarios that respect the complexity and diversity of all hominin species. By speculating within reasoned bounds, we aim to paint a richer, more nuanced picture of our ancient relatives, highlighting their adaptability and successes across a variety of ecological settings without the anthropocentric bias that often accompanies traditional narratives. This speculative lens allows us to explore the “what ifs” of human evolution, offering a more inclusive and expansive view of our shared past.

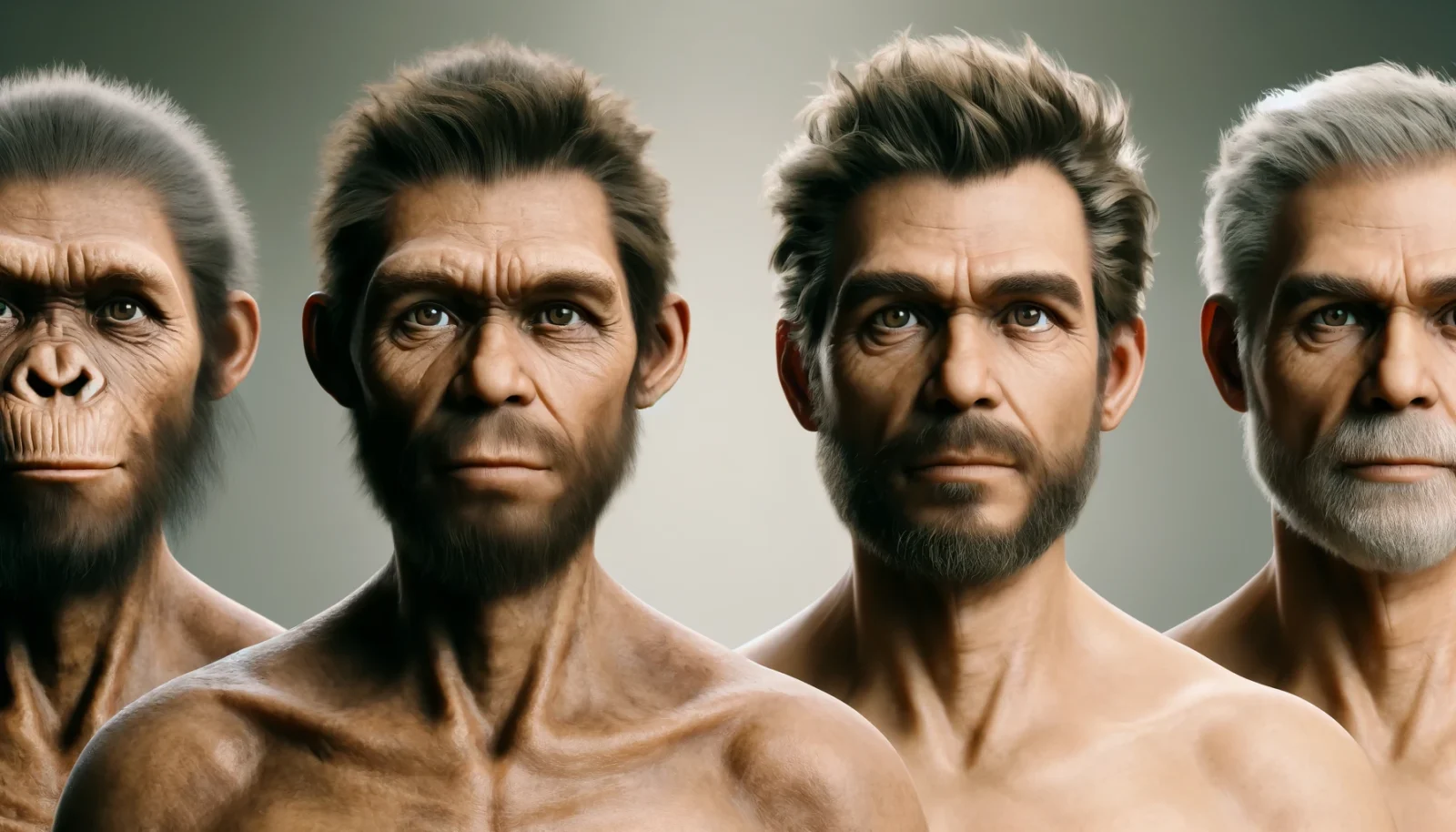

This narrative, while speculative, aims to encourage a deeper consideration of all hominin species as active, successful participants in their ecosystems, each contributing uniquely to the story of human evolution. The process by which new species arise is well-understood, the evidence compelling and conclusive, our knowledge complete. We can read the fossil record like a book and on these pages we see changes gradually accumulate over millennia.

Why focus on these two dates? These epochs serve as critical touchstones in the evolution of humanity, pivotal moments that help anchor our understanding of our ancient past. The year 700,000 BCE is particularly compelling for several reasons: it marks a period of significant development within Homo erectus—a species that had already been evolving for over half a million years and likely saw the emergence of several yet-to-be-discovered related species. This era is also notable for the evolution of the hyoid bone to more closely resemble that of modern humans, potentially enhancing speech capabilities. Imagine diverse hominin groups, spread across Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and parts of Asia, increasingly using their voices as a powerful tool for communication. Among these groups were the Dmanisi people, or Homo georgicus, who had reached regions including the Middle East and China as early as 1.8 million years ago and may have persisted until about 200,000 years ago, thus featuring in both of our speculative censuses. Known from remains found in Caucasus, these early pioneers are sometimes classified as a form of Asian Homo erectus.

Our second speculative census, set around 300,000 BCE, captures a moment shortly after the emergence of Homo sapiens in Africa. By this time, our own species had been expanding their range for approximately 15,000 years, encountering not just the Dmanisi people but also Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, and Neanderthals. This juncture was selected to explore the interactions between Homo sapiens and these other hominins—assessing their numbers and the extent of their geographical spread. This moment in prehistory offers a fascinating snapshot of a world where modern humans were not yet the dominant force, sharing the planet with a variety of other hominin species, each adapting to a rapidly changing world.

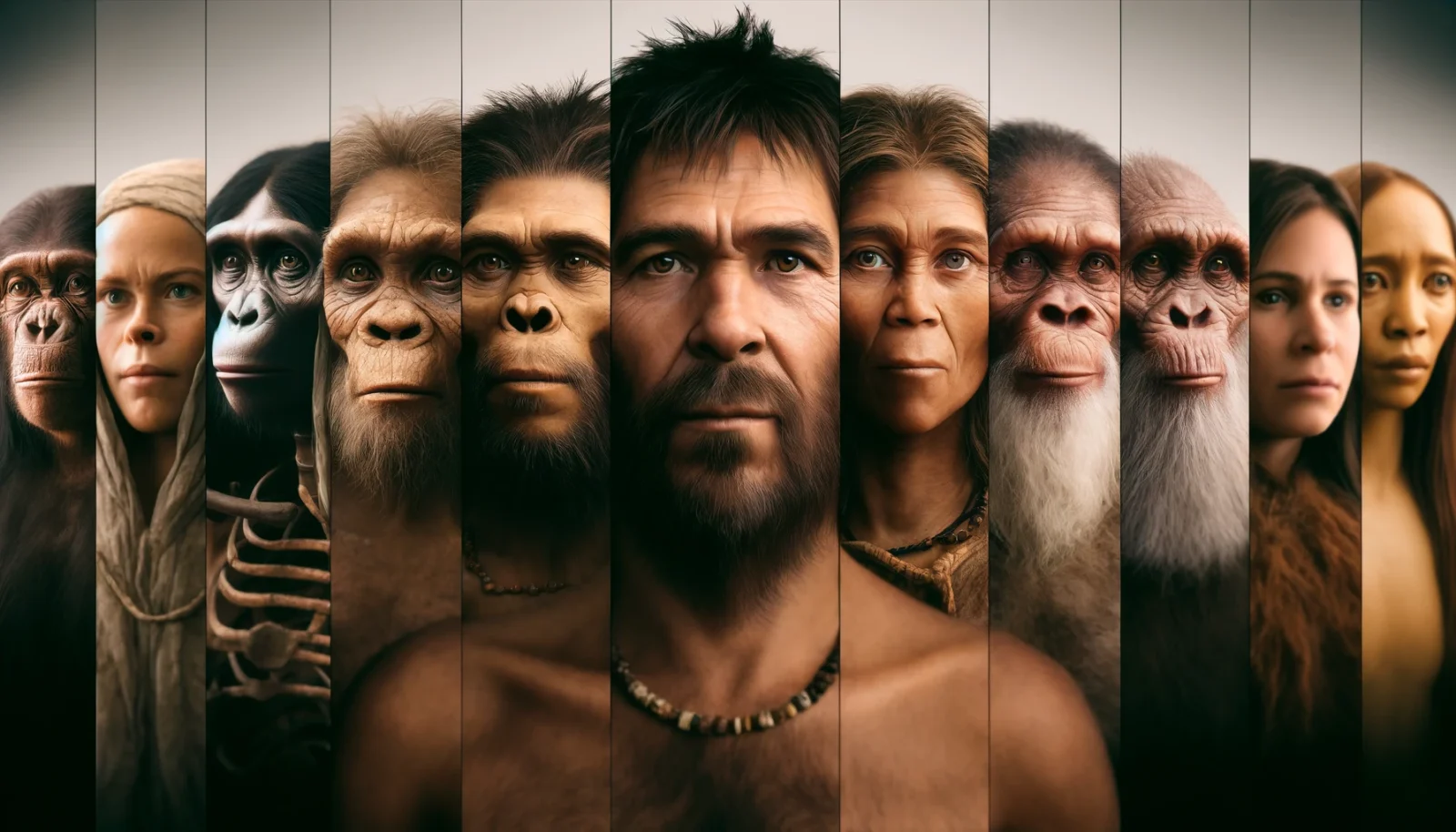

The narrative of human evolution is often constrained by the tangible—fossils, artifacts, and DNA remnants. Yet, much remains beyond the reach of these physical traces, hidden in the vast uncharted chapters of our ancestors’ lives. Here, we dare to imagine the expanses of early hominin societies, drawing parallels with the known populations of today’s great apes—our closest living relatives. These comparisons open a window to a world where early hominins, such as Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis, roamed widely across Africa and Eurasia, adapting to, and transforming, a multitude of environments.

As we delve into this speculative analysis, it is crucial to recognize the inherently hypothetical nature of such estimates. Yet, these educated guesses allow us to ponder the social structures, migrations, and survival strategies that might have characterized these early humans, providing a dynamic tableau of our evolutionary journey. Through this lens, we not only recount numbers but also reflect on the profound ecological impacts these early hominins had—impacts that shaped the world across millennia and laid the groundwork for modern human civilization.

This exploration is not merely an academic exercise; it is a narrative reconstruction that challenges us to think broadly and deeply about our ancient origins and the legacies left by those who walked the earth long before us.

Population Census: 700 Thousand Years Ago

Two million hominins in Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia! Our first of two speculative population censuses takes us back to the year 700,000 BCE, a time when the Earth was characterized by fluctuating climates that marked the Middle Pleistocene. This era witnessed a series of glacial and interglacial periods, which profoundly shaped the landscapes and ecosystems that hominins inhabited. Vast grasslands and expansive forests provided both challenges and opportunities for survival, influencing hominin adaptations and migrations.

While our fake census is highly speculative, it is grounded in a rational analysis of great ape populations today. Other than humans, today’s smartest primates—chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans—have a combined population in the wild of approximately 400,000 to 700,000. These numbers persist despite their near-complete inability to expand beyond their current ideal environments—a restriction no human species has faced since before Homo habilis.

Drawing from these numbers, the prominent hominins in 700,000 BCE, including Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Neanderthal ancestors, and possibly Denisovans, were navigating a world without the borders defined by modern civilization. Although precise population estimates are elusive, considering Homo erectus‘ longevity—having thrived for over a million years—it’s plausible their numbers were substantial. Assuming they were three times more successful than today’s great apes suggests a speculative global population of 1.2 to 2.1 million. This estimate encompasses “worldwide” regions within Africa and Eurasia, areas within the walking range of these ancient peoples.

Species Interbreeding

One surprising aspect of ancient human evolution is the ability of different species to interbreed. Some ancient humans appear to have been capable of producing viable offspring when encountering other closely related groups. For example, evidence hints that Homo habilis and Homo erectus, coexisting around 1.5 million years ago, might have interbred with some success. Similarly, later hominins like Homo erectus, Homo antecessor, and Homo heidelbergensis, all present in Africa around 700,000 years ago, likely interbred to some degree. These interbreeding events played a significant role in shaping our evolutionary history.

Reflecting on the complexity and diversity of species interbreeding further, consider the example of modern gorillas. Eastern and Western gorillas do not interbreed in the wild. They are distinct species that diverged approximately 1 to 2 million years ago. While there have been instances of hybridization between these two species in captivity, primarily driven by zoo breeding programs, such practices are no longer encouraged due to the desire to maintain genetic purity. Research suggests that there might have been some interbreeding between these populations for a period after their initial divergence, indicating that complete genetic isolation occurred more recently than the initial split, possibly only about 80,000 to 200,000 years ago.

Weekly Wisdom Builder

Got 4 minutes a week?

A new 4-minute thought-provoking session lands here every Sunday at 3PM, emailed on Mondays, and shared throughout the week.

Exactly what the world needs RIGHT NOW!

Homo erectus Census Link

The intricate tapestry of early human migration in Southeast Asia is highlighted by the intriguing stories of Homo luzonensis, Homo floresiensis, and Homo erectus, particularly the Java Man. These species collectively provide a fascinating glimpse into the adaptability and diversity of early hominins in this region.

When considering the potential hominin population across the islands of Greater Malaysia, Java, Flores, Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines, it is conceivable that each habited island might have supported a few thousand individuals at a minimum. During the peak of their collective heyday, combining all hominin species, the total population at times could potentially have reached over 100,000. This estimate is highly speculative but highlights the possible extent of ancient human and hominin dispersal and adaptation to these lush, resource-rich environments. Such numbers would depend on numerous factors, including environmental conditions, available technology, and the biological capabilities of each species.

Homo luzonensis, discovered in Luzon, the Philippines, dates back approximately 67,000 to 50,000 years ago. This relatively recent find adds a new dimension to our understanding of human evolution in Southeast Asia. While not directly linked to Homo erectus, the presence of Homo luzonensis suggests a complex pattern of hominin activity in the region, possibly indicative of multiple migration waves and localized evolutionary developments. Their unique physical traits and the tools associated with them hint at a distinct way of life, adapted to the challenges of their environment.

Moving southward, the story takes us to the island of Flores, where Homo floresiensis, affectionately known as the “Hobbit,” thrived from about 190,000 to 50,000 years ago. The discovery of this diminutive hominin challenged previous notions about the geographical and ecological limits of early human migrations. Despite its small stature and brain size, Homo floresiensis exhibited advanced tool-making skills that were sophisticated enough to support their survival in isolated island conditions. Their presence on Flores raises questions about whether they evolved from a population of Homo erectus that became isolated and underwent significant physical changes due to island dwarfism.

Further west, in Java, the well-documented Homo erectus, specifically known as Java Man or Homo erectus erectus, provides a direct connection to one of the earliest known hominin migrations out of Africa. Dating back to as much as 1.8 million years ago, these early humans represent a significant chapter in our prehistoric narrative. Java Man exemplifies the classic features of Homo erectus with its considerable brain size and more modern human-like body proportions, which were well-suited to a variety of ecological niches across Asia.

These linked stories from Luzon, Flores, and Java illustrate a broader narrative of hominin dispersion that emphasizes both the adaptability and complexity of early human life. Each population adapted uniquely to their local environments, suggesting a dynamic interplay of genetics, culture, and geography that shaped the evolution of Homo erectus and its relatives. As we delve deeper into these connections, we continue to unravel the intricate web of human history, revealing the resilience and ingenuity of our ancient ancestors.

Homo erectus, deeply entrenched in various ecological niches, could have numbered around one million across Africa and Asia, including regions now known as China and Indonesia. Sometime around 1.2 million years ago, the flexible keratin genes responsible for traits like scales, fur, feathers, hair, nails, and beaks started doing their thing. It’s around this time that our “less fur” genes started exhibiting as the climate got warmer and our ancestors started chasing big game: less hair was beneficial.

Homo Heidelbergensis

Homo heidelbergensis, likely ancestors to both modern humans and Neanderthals, were burgeoning in Africa, possibly numbering around one hundred thousand. Their emerging intelligence and budding linguistic capabilities may have propelled their expansion into Europe and further into Asia. At this stage, the ancestors to Neanderthals, derived from Homo heidelbergensis migrants in Europe, might account for only a few thousand to tens of thousands. The remainder of this hypothetical two million might include smaller populations of less-documented hominin species yet to be discovered.

Each hominin species roamed various parts of the world, adapted to their unique environments with varying degrees of tool use, social structure, and mobility. Homo erectus, likely the most widespread of the hominins, had already spread from Africa into Asia and parts of Europe, known for their use of simple stone tools and control of fire. Homo heidelbergensis, emerging around this time, is thought to be a direct ancestor of both Neanderthals and modern humans, beginning to show more advanced behaviors including more sophisticated tools and possibly early forms of hunting cooperation and shelter construction.

The Neanderthal ancestors in Europe, possibly represented by populations evolving from Homo heidelbergensis, were adapting to colder climates, developing the physical traits that would later define classic Neanderthals. These groups were likely small and dispersed, adapting to the ecological niches of Pleistocene Europe. Denisovans, though direct evidence from this exact period is lacking, genetic studies suggest that the Denisovan lineage had also branched off by this time, occupying parts of Central and East Asia.

This period marked a critical phase in hominin evolution, characterized by significant migrations and environmental adaptations. The ability to manipulate fire and develop new technologies was becoming a defining trait of these groups, setting the stage for the later emergence of more sophisticated cultures and technological innovations. The speculative nature of this narrative is based on pieced-together evidence from fossil records, archaeological findings, and genetic data. As such, this portrayal should be seen as a broad sketch of what might have been, rather than a definitive account. Each region would have witnessed different challenges and evolutionary pressures, influencing the survival and development of these early human ancestors.

Population Census: 300 Thousand Years Ago

Three million hominins spread even further! Fast forwarding 400,000 years, we arrive at our second census. This pivotal moment in prehistory marks the emergence of Homo sapiens, yet they were just one of many players on the ancient stage.

At this time, the population of Homo sapiens and their immediate ancestors in Africa was likely only a few hundred thousand. However, the broader tapestry of hominin success across the globe was flourishing more than ever.

Though highly speculative, estimates for the global hominin population at this juncture could reasonably range from 2 to 3 million as various human species continued their migration into more nooks and crannies of available territories. These hominins were adept at buckling down in micro-niches, exploiting the rich mosaic of environments that spanned from the lush forests of Africa to the rugged terrains of Eurasia. This increase from our earlier census reflects not just the continuous reproduction but also an aggressive expansion into diverse ecological niches. At this time, the landscape still offered relatively vacant lands, allowing for this expansion without the severe constraints of competition or environmental changes that would later shape their evolutionary paths. This estimate draws from the current combined population of chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans, which ranges from approximately 400,000 to 700,000—using these numbers as a touchstone and considering a modest growth rate that reflects improved survival strategies and habitat exploitation by hominins.

As these populations expanded, the groundwork was being laid for the complex interplay of competition and cooperation that would eventually lead to the dominance of Homo sapiens. The journey of these early hominins, from spreading across continents to refining their ecological and social strategies, foreshadows the evolutionary pressures that would sculpt the survival of the fittest, culminating in a world predominantly inhabited by modern humans.

This period was marked by significant evolutionary developments. In Africa, nascent Homo sapiens accounted for just a fragment of the broader hominin population, while established species like Homo heidelbergensis continued to thrive, a testament to their adaptive success across various African environments. Meanwhile, in Europe and Asia, Neanderthals and Denisovans were honing their adaptations to their challenging climates, utilizing sophisticated tools and developing complex social structures that likely bolstered their resilience and survival.

While significant populations were present in Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and Asia—including burgeoning groups in China—hominins had yet to reach the Americas or the Oceania-Australasia zone. This distribution underscores the extensive yet uneven spread of hominins across the Old World, shaped by migrations, environmental pressures, and interspecies interactions.

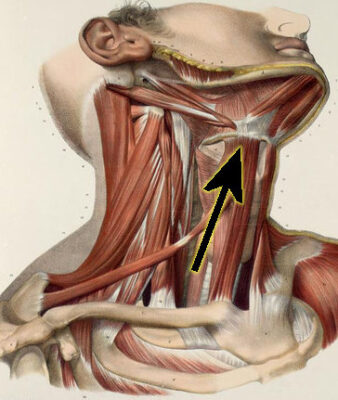

Speech: Let’s Touch Base

During this era, around 300,000 years ago, many ancient humans roamed the Earth, and it is certain that some of these human species could talk and tell stories, passing on information from one generation to the next—a clear demonstration of cultural transmission. The extent to which different species could communicate and the sophistication of their language remain speculative. With the discovery of ancient art associated with neanderthals, it becomes very likely that neanderthals and denisovans could speak, and that speech evolved in an earlier species. It’s also very likely that their ancestor Homo heidelbergensis could speak as well, indicated by their anatomically evolved hyoid bone. The specifics of the languages of these human species and their various disparate groups are likely to remain unknown. It’s reasonable to assume that some of these ancient humans could at least tell simple stories. Certainly, Homo sapiens could, and it’s very likely neanderthals, denisovans, and Homo heidelbergensis did as well.

Before these species, the rest is more speculative, but we can make educated guesses grounded in the evidence available. While the fossil record is limited, we have to remember that a lack of evidence is not evidence. And here’s the kicker, there is no definitive evidence to suggest that hominins before Homo heidelbergensis lacked the capacity for speech. It’s very possible their ancestor Homo erectus and its ancestor Homo habilis spoke. Their complex lifestyles, command of fire and tools, and pioneering spirits fostered a need for communication. Species that roam have to say simple things like “this way,” “let’s go over there,” and “there’s food over there.”

While even more speculative, it’s also possible that speech started to evolve in ancient hominin species before Homo habilis 2.3 million years ago. Given that chimpanzees do not speak, it’s reasonable to assume speech evolved sometime between 6 million and 700,000 years ago. My best estimate right now is that most hominin species could speak simply and tell simple stories as early as 2 to 4 million years ago with the evolution of Homo habilis or before. These earliest hominins had a pioneering spirit which I think required the ability to speak.

It is based on the observation of complex social behaviors in earlier hominins, which likely required some form of communication beyond mere gestures or sounds. The development of larger and more complex brain structures over millions of years suggests an increasing ability to process and produce more sophisticated forms of communication. Tool use and cooperative hunting strategies, evident in archaeological findings from these periods, also imply a level of planning and cooperation that could be facilitated by rudimentary forms of speech. Additionally, the progressive increase in brain size and complexity among hominins correlates with the potential for linguistic development. Thus, while direct evidence for speech in these ancient hominins remains elusive, their behavioral patterns and neurological advancements provide compelling circumstantial evidence that speech, at least in its most elementary forms, may have been part of their evolutionary trajectory long before Homo sapiens emerged.

While these ancient hominins before Homo habilis might have spoken, it’s unlikely they held meetings, ceremonies, or summits with other groups. Considering modern examples of language barriers, it is highly unlikely that different ancient hominin groups could engage in complex conversations with each other.

Focusing on how it all started, even with no evidence, we can speculate. Speech likely started as the ability to “vocally articulate” within a tribe and especially within extended family units. How often this matured into precise words passed down to offspring, what we consider a language, remains one of the great unknowns in the study of our ancestors. Sometimes, I like to think about when the first bilingual hominin existed. I like to conduct thought experiments pondering early attempts at signaling family members, the first words and languages, and even whether early multilingual people evolved before or after the first languages.

Final Acts: Ancient Human Extinction Events

The twilight of a species is a poignant tale, one that repeats itself throughout the annals of evolutionary history. As Homo sapiens ascended, our ancient relatives began to vanish, leaving behind a trail of clues and unanswered questions. The exact timing and circumstances of their extinction remain shrouded in mystery, but we know that competition, pandemics, and environmental shifts often conspired against them. The last member of each species, a solitary figure, walked the earth unaware of their distinction – the final link in a chain of existence that would soon be broken. Their story, a testament to the fragility of life, beckons us to explore the poignant history of human extinctions. For a glimpse into this sad story, check out Human Extinction Events: From Homo habilis to the Neanderthals.

The Future is Bright

In this exploration of ancient hominin populations, we have ventured into the realms of speculation informed by a comparative analysis of existing great ape populations. My optimism as a writer and thinker may indeed tilt these estimates towards the upper end of the spectrum. This optimism is rooted in a belief in the adaptability and resilience of early hominins, qualities that have defined human evolution across millennia.

It is important to note that scientific methodologies for estimating ancient populations are still in their nascent stages. These methods, which include analyzing the distribution of fossil finds and correlating them with carbon-dated artifacts, are continually being refined. As such, they provide a framework for inferring population densities over time but are yet to reach their full potential. Over time, we anticipate that these approaches will mature, bolstered by yet-to-be-discovered empirical data and enhanced estimating techniques.

As new discoveries emerge and analytical technologies advance, our understanding of early human demographics will evolve, offering more grounded and precise estimates. This ongoing process not only broadens our appreciation of the diversity and adaptability of our hominin ancestors but also underscores the complexities involved in piecing together their existence from the fragments they left behind.

Through this speculative journey, we aim to deepen our understanding of the human story, tracing the broad ecological footprint of those who walked the Earth long before us. This narrative is not merely about numbers; it’s about piecing together the vast, intricate puzzle of human evolution and preparing for future discoveries that will inevitably reshape our understanding of our ancient origins.

— map / TST —

Discover the journey of human thought…

To fully understand your context within the universe, nothing can replace reading the full story of human thought. My latest book, my 15th, tells the story of our best and current ideas from 2600 BCE to today, all from our modern viewpoint and understanding. With a modern perspective, it weaves together history, science, and philosophy to illuminate the intricate web of human thought. Embark on this journey and witness the remarkable evolution of our ideas through the ages.

Coming December 2024: Immerse yourself in knowledge, not snippets.

- Discover how 30 influential philosophers shaped our understanding of the world.

- Explore the concepts that continue to influence science, art, and culture today.

- Get your copy now and start thinking like the greatest minds in history!