Series: TST Framework | Five Thought Tools | Four Mind Traps | Three Truth Hammers

Logical Fallacies: One of the Four Mind Traps.

Abstract: In this new look at logical fallacies, 26 of them are used to explain the 4 strategies: distraction, faulty choices, faulty evidence, and linguistic trickery. A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning which makes the argument invalid. They occur when a conclusion does not logically follow from the premises, resulting in a non sequitur. These fallacies often rely on emotional appeals and falsehoods, making them particularly effective on those susceptible to confirmation bias. Regrettably, logical fallacies are commonly found in poor journalism and unscrupulous politics, while responsible journalism and politics strive to avoid them. Logical fallacies are one of the Four Mind Traps, which is part of the TST Framework. The Five Thought Tools, which helps you gather, frame, and communicate accurate information, is also part of the TST Framework.

Logical fallacies are not always wrong, but they are always meaningless.

Logical fallacies are not always wrong, but they are always meaningless.

As part of the mind traps, logical fallacies play a crucial role in the TST Framework. Familiarizing oneself with logical fallacies can help improve one’s critical thinking skills by allowing self-assessment for flawed arguments and recognition of valid or invalid opposing arguments.

Issues with valid arguments on both sides can be more challenging to resolve, as seen in the abortion debate, where arguments center around defining the beginning of life. The various perspectives on when life starts, such as at conception, heartbeat detection, brain formation, or birth, all have valid arguments, making the discussion more intricate and requiring deeper examination of each argument’s validity.

On the other hand, issues with only one valid argument can be more easily resolved, as opposing arguments would rely on logical fallacies rather than sound reasoning.

Four Strategies for 26 Logical Fallacies

As you read a summary of each keep in mind that just because someone uses a logical fallacy does not mean they’re wrong about the argument, it just means they have yet to make a valid argument.

Latin Note: I love Latin and included it below, sorry. My only excuse is that I love Latin, and Latin is frequently cited when discussing logic. I think this is because logic and Latin are linked historically.

Strategy I: Distraction

If your argument is bad, distract your audience. Distraction fallacies divert attention from the core issue by using invalid associations, irrelevant points, or emotional manipulation. These tactics aim to mislead the audience and prevent logical examination of the argument.

Distraction Type: Association Problems

Weakening your opponent’s position. Humans are naturally inclined to avoid bad things. If something bad happens, we tend not to repeat it. Additionally, if something is similar to something that is bad, we tend to avoid it. This psychological tendency to shun negative associations can lead us to commit logical fallacies in arguments. These fallacies all involve linking an argument or person to something perceived as negative, thereby invalidating the argument through association rather than addressing its merits. Personal Attack, Guilty by Association, and Straw Man are examples of such fallacies. Each one undermines an argument by associating it with negative traits, entities, or distorted versions of the original argument, diverting attention from the actual issues at hand.

1. Personal Attack

Latin: ad Hominem, "to man," or "to the person"

The “low blow” of logical fallacies is the ad hominem attack. Instead of addressing the argument, it targets the person making it. A clever trick, but a fallacy nonetheless. The question uses a playful metaphor (“low blow”) to grab attention, while the answer concisely explains the concept and its flaws. Feel free to modify it to fit your style! A.k.a. poisoning the well. With this fallacy, you use an insult as an argument.

Example 1,

“Liberals/Conservatives always say _____.”

Example 2,

“Person one’s preacher said a few things I think were anti-American and bad, therefore that person is anti-American and bad.”

Example 3,

“Person two is a Nazi.”

All of these are invalid arguments and say nothing. To respond, just point out the insult as a logical fallacy and simply ask if they want to present a valid argument. If mixed with other arguments, point out the name calling and only address the rest of the argument.

2. Guilt by Association

Latin: argumentum ad odium, "argument to spite"

A variation of the ad hominem fallacy is guilty by association, where someone is judged based on their connection to something else or to others, rather than their own actions or arguments. This fallacy assumes that a person’s beliefs or character are defined by the company they keep, rather than their own merit.

Example:

“John is friends with a known criminal, so he must be a criminal too.”

In this example, John’s association with a criminal is used to make a judgment about his own character, without any evidence of his own wrongdoing. This fallacy ignores the possibility that people can have diverse friendships and connections without sharing the same beliefs or behaviors.

Remember, a person’s ideas and actions should be evaluated on their own merit, not based on who they associate with. When encountering this fallacy, ask for evidence of the person’s own actions or arguments, rather than their connections to others.

3. Straw Man

Latin: ignoratio elenchi, "ignorance of the refutation"

With this fallacy, you hold up a position that someone does not hold, and then tear it down. Usually the position is weak or ridiculous and easily knocked down.

A good reply,

“You are attacking a position I do not hold. I am not arguing that _____. My position is _____.”

For example, one might argue that,

“Democrats want open borders which will allow criminals into America.”

The reality is that is an argument Democrats are not making. If we have open borders, then criminals would indeed come in more easily. That is true, but Democrats are not arguing for completely open borders.

A sample reply:

“You are attacking a position I do not hold. I am not arguing that I want open borders, nor am I arguing that I want to allow criminals into America. My position is that I want a lawful immigration policy that is consistent, not racist, and abides by international law including the Geneva convention.”

Distraction Type: Slight of Hand

Introducing irrelevant information. In arguments, some tactics aim to divert attention away from the core issue by introducing irrelevant or misleading information. These distractions can derail logical reasoning and obscure the truth.

Red Herring and Appeal to Hypocrisy are prime examples of such fallacies. By shifting focus away from the main argument, these tactics prevent a thorough examination of the issue at hand.

4. Red Herring

Latin: ignoratio elenchi, "ignoring the refutation" or "missing the point"

A red herring is a logical fallacy that occurs when an irrelevant topic is introduced into an argument to divert attention from the original issue. The purpose of a red herring is to mislead or distract from the central point, effectively preventing a clear and focused discussion of the topic at hand. This technique can be particularly misleading because it shifts the debate to ground that is more favorable to the person using the fallacy.

For example, during a discussion about the effectiveness of environmental regulations, if someone suddenly shifts the conversation to the high salaries of CEOs in the oil industry, they are introducing a red herring. The new argument about CEO salaries, while possibly of interest, does not address the original question regarding the regulations’ effectiveness and serves only to distract from the substantive issues under discussion.

5. Appeal to Hypocrisy

Latin: tu quoque, "you also"

An appeal to hypocrisy is when a person counters an argument by pointing out hypocrisy in the opponent’s position, rather than addressing the merits of the argument itself. This fallacy attempts to discredit the opponent’s argument by suggesting that their actions or words are inconsistent with the position they advocate, thereby implying that the argument is invalid.

For example, if someone argues that we should reduce our carbon footprint to combat climate change, and another person responds,

“But you drive a car and fly in airplanes all the time!”

they are committing an appeal to hypocrisy. This response doesn’t engage with the argument about reducing carbon footprints or the validity of combating climate change; instead, it attempts to discredit the speaker by highlighting a perceived inconsistency in their behavior. This fallacy deflects from the actual issue and does not provide a logical response to the argument presented.

Weekly Wisdom Builder

Got 4 minutes a week?

A new 4-minute thought-provoking session lands here every Sunday at 3PM, emailed on Mondays, and shared throughout the week.

Exactly what the world needs RIGHT NOW!

Distraction Type: Emotional Manipulation

Appealing to emotions over logic.

6. Appeal to Emotion

Latin: Argumentum ad Passiones, "argument to passions"

An “Appeal to Emotion” occurs when an argument is made by manipulating emotions rather than by using valid reasoning. This fallacy aims to exploit the emotional vulnerabilities of others to win an argument, instead of presenting factual evidence or logical reasoning.

In a debate about environmental policy, instead of citing scientific data or economic arguments, a politician says,

“Think of your children and grandchildren suffering in a world where the forests are gone, the air is unbreathable, and the rivers are so polluted they can no longer sustain life. We must act now to protect our planet!”

Here, the politician is appealing to the audience’s fears and emotions about future generations, rather than focusing on the practical implications and scientific data related to environmental policy. This can divert attention from the actual merits of the policy and influence decisions through emotional impact rather than rational debate.

7. Appeal to Fear

Latin: argumentum ad metum, "argument to fear"

Scaring people into accepting a conclusion. The appeal to fear fallacy attempts to persuade someone by invoking feelings of fear or insecurity. It plays on our natural aversion to threats and risks, often exaggerating dangers or using scare tactics to manipulate our judgment. The argument itself lacks strong evidence and relies on emotional manipulation rather than sound reasoning.

Example:

“We absolutely must pass this law to increase security at the border. If we don’t, dangerous criminals will flood our country and put our families at risk!”

In this example, the argument for stricter border security relies on the fear of crime without providing evidence that the current measures are inadequate or that stricter measures would definitively stop criminals.

Note: Appealing to fear can be a powerful motivator, but it’s important to separate legitimate concerns from unfounded scare tactics. Critical thinking and evidence-based reasoning should guide our decisions, rather than emotional manipulation.

8. Appeal to Pity

Latin: Argumentum ad Misericordiam, "argument to mercy"

Trying to win an argument by evoking sympathy, not logic. For example:

“You have to let me pass, I haven’t slept in days!”

The appeal to pity fallacy, or “Fallacy of Compassion,” attempts to win someone’s support or agreement by evoking sympathy or compassion. It relies on pulling at the heartstrings rather than presenting sound logic or evidence. While empathy is important, decisions based solely on pity can be illogical.

Example:

“You can’t possibly give me a failing grade on this paper! I’ve been working so hard all semester, and my grandma is sick. If I don’t get a good grade, I won’t be able to get a scholarship.”

In this example, the student is trying to avoid a bad grade by appealing to the teacher’s pity regarding their personal circumstances, not by focusing on the quality of the work itself.

Note: While empathy and compassion are important values, they should not replace critical thinking and evidence-based reasoning in decision-making. Appealing to pity can be a red herring, distracting from the actual issues at hand.

Strategy II: Faulty Choices

Control their choices! Give them bad choices. Faulty Choices present misleading or limited options to influence decisions. This strategy includes false equivalences, false choices, and errors in causal reasoning, steering the audience towards flawed conclusions.

Faulty Choice Type: Quality

Humans naturally seek and appreciate having choices, trusting that the options presented are the ones that matter. However, this trust can be exploited, leading to logical fallacies that manipulate our perception of the available options. False Equivalence and False Choice are two such fallacies that compromise the quality of choices. These fallacies distort the decision-making process by presenting misleading options or false comparisons.

9. False Equivalence

Latin: Falsus Equivalens, "False Equivalent"

A false equivalence is an equivalence made between two subjects based on flawed or false reasoning. This fallacy is committed when one shared trait between two subjects is assumed to show equivalence when it does not exist.

A false equivalence occurs when an anecdotal similarity is pointed out as equal, but are not. To be a false equivalence, the claim of equivalence must break down under scrutiny. This error is usually because of an oversimplification or because it is ignoring additional factors.

The pattern of a false equivalence is:

“X = a + b, and Y = a + c. Since they both contain a, X and Y are equal.”

When reduced to math, you can easily see that a false equivalence is bad math, bad logic. Just because two equations have the same value in them does not mean the two equations are equal. That’s silly and easily disproved. Likewise, just because two arguments have a thing in common does not mean they are equal. That too is silly and easily disproved.

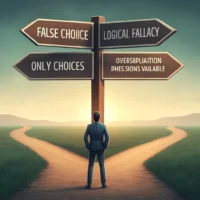

10. False Choice

Latin 1: Falsum Dilemma, "A false dilemma" Latin 2: Aut Caesar, Aut Nullus, "Either Caesar or nothing"

A false choice is when you reduce the choices down to two or sometimes three choices but there are actually more choices available.

A false choice, also known as a false dilemma, false dichotomy, or even a Black and White Fallacy, is a type of logical fallacy—an error in reasoning. This fallacy occurs when an argument incorrectly presents only two options or outcomes in a situation, implying that these are the only possible choices when, in fact, other alternatives exist. The essence of a false choice lies in its oversimplification of complex issues, forcing an either/or decision that doesn’t accurately reflect the full spectrum of possibilities.

For example, consider the statement: “You’re either with us, or you’re against us.” This presents a situation as having only two opposing sides, ignoring any middle ground or nuanced positions that might exist. By simplifying scenarios in this manner, a false choice pressures individuals to make decisions without considering all available options, leading to potentially flawed conclusions.

Faulty Choice Type: Causal Traps

Use patterns to deceive. Humans are naturally inclined to find patterns and connections between events. However, our brains can sometimes lead us astray, particularly when it comes to cause and effect. Here, we’ll explore two common causal fallacies: Slippery Slope and False Cause.

11. Slippery Slope

Latin: Declivitas Cadens, "Slope falling or slipping"

Humans often worry about the potential consequences of their actions, fearing that one small step might lead to a series of negative outcomes. A slippery slope argument suggests that taking a small initial step will inevitably lead to a series of increasingly negative consequences, often presented in a dramatic way. This creates a mental image of a downward slope where one misstep leads to a catastrophic fall.

Here’s a breakdown of the Slippery Slope fallacy:

- Structure: It starts with a seemingly reasonable position and then extrapolates it to an extreme outcome, often without evidence.

- Problem: It relies on speculation and fear-mongering instead of a solid understanding of cause and effect.

- Impact: It can discourage critical thinking and lead to decisions based on exaggerated fears rather than on facts.

Example:

“If we allow students to redo assignments to improve their grades, next they’ll want to retake entire courses, and soon they’ll expect to get degrees without doing any work at all.”

This statement assumes, without evidence, that a minor accommodation like assignment redos will automatically lead to students expecting a free degree. It ignores the possibility of setting clear boundaries and establishing reasonable limits.

Key Takeaway: Be wary of arguments that rely on worst-case scenarios and a chain reaction of negative consequences without providing solid evidence for each step.

12. False Cause

Latin 1: Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, "after this, therefore because of this" Latin 2: Cum Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, "With this, therefore because of this"

The False Cause fallacy, also known as “post hoc ergo propter hoc” (Latin for “after this, therefore because of this”), occurs when someone mistakenly assumes that because one event happened before another, the first event caused the second. This is a common error in logic because simply observing two events in sequence doesn’t guarantee a cause-and-effect relationship.

Here’s why False Cause is a fallacy:

- Mistaking Correlation for Causation: Just because two things happen together doesn’t mean one caused the other. There could be another, unseen factor influencing both events.

- Coincidence: Sometimes, events simply coincide without any causal connection.

Example:

“It rained after I washed my car, so washing my car must cause rain.”

In this case, washing the car and the rain are more likely to be coincidental events due to weather patterns, not a cause-and-effect relationship.

Key Takeaway: Be cautious of arguments that assume a causal link between events simply because one happened before the other. Consider alternative explanations and look for evidence of a direct causal relationship.

13. Appeal to Consequences

Latin: argumentum ad consequentiam, "argument to consequence"

Arguing that a conclusion is true or false based on its potential consequences rather than its actual truth value.

“We shouldn’t invest in renewable energy because it might put fossil fuel workers out of a job.”

It’s not that consequences shouldn’t be looked at, they should. The “Appeal to Consequences” fallacy often involves exaggerated bad consequences and sometimes outright lies. This fallacy occurs when the truth of a claim is argued based on the desirability of its consequences—either positive or negative. By exaggerating the consequences, the argument manipulates emotions and diverts attention from the actual truth or falsity of the claim. Exaggerated consequences can lead to heightened emotional responses, making it more likely that people will accept or reject a claim based on how they feel about the outcomes, rather than on logical reasoning or empirical evidence. This can significantly skew rational decision-making and debate.

Strategy III: Faulty Evidence

Give them bad choices. Control their choices! Faulty Choices present misleading or limited options to influence decisions. This strategy includes false equivalences, false choices, and errors in causal reasoning, steering the audience towards flawed conclusions.

Faulty Evidence Type: Hiding

Where’s the Proof? In the pursuit of truth and understanding, evidence is crucial. However, some arguments attempt to persuade by obscuring, omitting, or misrepresenting evidence. These tactics can lead to flawed reasoning and misinformed conclusions. Hasty Generalization and Circular Argument are examples of such fallacies. Each of these fallacies sidesteps the need for solid evidence, either by making broad claims without sufficient proof or by using the conclusion as the premise to create an illusion of support.

14. Hasty Generalization

Latin: Secundum Quid, "according to a certain thing"

A hasty generalization fallacy occurs when someone makes a broad claim based on a limited or unrepresentative sample. This fallacy assumes that what is true for a small group or specific case will automatically be true for a larger group or other cases. It is insufficient evidence, stereotyping, overstatement such as

“all the time”

A hasty generalization is a logical fallacy that occurs when someone makes a broad conclusion based on insufficient or non-representative evidence. Essentially, this fallacy involves drawing a general rule from a single, often atypical, event or a small sample that is not large enough to hold up to statistical scrutiny. The error lies in the leap from an individual or minimal data points to a universal rule without considering all relevant variables or a sufficient amount of evidence.

For example, if someone visits a city for the first time, experiences poor service at a restaurant, and concludes,

“The service in this city is terrible,”

they are making a hasty generalization. This judgment is based on a single instance, which is insufficient to accurately judge the overall quality of service across the entire city.

15. Circular Argument

Latin: petitio principii, "begging the question"

A.k.a. begging the question. A circular argument repeats something assumed to be true in the conclusion. The first thing still needs to be proven. These fallacies are presumptuous.

Example,

“God’s miracles prove he exists because I have witnessed his glory all around me.”

A circular argument is the error where the conclusion of an argument is assumed in the premise. Essentially, the argument goes around in a circle by stating the same assertion in different words, without providing any actual evidence to support the conclusion. This makes the argument invalid as it relies on its own premise to prove itself, which fails to add new or conclusive information to the discourse. For example, if someone argues,

“Reading fiction is valuable because it is beneficial to read imaginative literature,”

they are using circular reasoning. The claim that fiction is valuable is merely restated as being beneficial, without explaining or proving why it is beneficial.

16. Suppressed Evidence:

Latin: Argumentum ex Silentio, "argument from silence"

Intentionally ignoring or hiding relevant information. This fallacy occurs when someone presents an argument or makes a claim while intentionally withholding or omitting relevant evidence that contradicts or undermines their position. It involves cherry-picking data, hiding contradictions, or disregarding inconvenient facts to create a misleading narrative.

Example: A politician claims that a new policy has been a huge success, citing only positive statistics and testimonials, while deliberately omitting reports of widespread criticism, negative consequences, and expert warnings.

In this example, the politician is presenting a one-sided argument, suppressing evidence that contradicts their claim, and creating a misleading impression of the policy’s effectiveness.

Note: Suppressed evidence can be a deliberate attempt to deceive or manipulate others. It’s essential to seek out comprehensive information, consider multiple sources, and critically evaluate arguments to uncover potential suppressed evidence.

Faulty Evidence Type: Interpretation

Arguments sometimes rely on the manipulation of authority and the misuse of evidence to persuade. These tactics can create a false sense of credibility and mislead the audience about the strength of the argument. Appeal to Ignorance, and God of the Gaps fallacies exploit our reliance on perceived authority and the misuse of evidence, leading to flawed conclusions and undermining logical reasoning.

17. Appeal to Ignorance

Latin: argumentum ad ignorantiam, "argument to ignorance"

With this fallacy, you use the fact that we do not know something to imply something else is either true or false. Ignorance (not knowing) is not evidence. Commonly said as,

“a lack of evidence is not evidence.”

Just because you can’t prove something, does not mean it’s true, nor false.

Example,

“Person one has not released his report yet, therefore person two did not commit any crimes.”

Example,

“We haven’t heard anything conclusive that Person one conspired with Russia, therefore he did nothing wrong.”

Example against God’s existence,

“We have no evidence God exists, therefore God does not exist.”

Example for God’s existence,

“We cannot prove God does not exist, therefore God exists.”

18. God of the Gaps

Latin 1: Deus Ex Machina, "god from the machine" Latin 2: Argumentum ad Ignorantiam Negativum, "argument to negative ignorance."

Similar to appeal to ignorance, the “God of the Gaps” occurs when gaps in scientific knowledge are taken as evidence or proof of God’s existence. Essentially, it involves using the lack of information or incomplete understanding in scientific explanations as a place to insert a supernatural explanation. This fallacy is particularly evident in discussions about phenomena that science has not fully explained yet, such as the origins of the universe or the complexities of biological processes.

For example, in debates about evolution, some may argue against its validity by pointing to the absence of complete fossil records for every stage of evolution from one species to the next. They might say,

“You can’t show exactly how these species evolved into each other; therefore, this gap in knowledge proves that a divine creator must have intervened.”

This argument focuses on specific uncertainties or undeveloped areas within evolutionary theory to discredit the extensive body of evidence supporting evolution, rather than addressing the overall scientific consensus and robust evidence that does exist.

The “God of the Gaps” fallacy is problematic because it relies on the current limitations of scientific understanding as supposed ‘proof’ of divine action, ignoring the potential for future discoveries and advancements that could fill these gaps. Moreover, it shifts the discussion away from scientific inquiry and evidence, turning it instead towards supernatural explanations that are not based on empirical evidence.

19. Cherry Picking

Latin: argumentum ad selectivum, "argument to the selective"

Selectively presenting only data that supports a conclusion while ignoring contradictory evidence. For example: A health supplement company claims,

“Studies show our product boosts immune function,”

by citing only the few studies with positive results.

Cherry picking is when someone presents only the data that supports their conclusion, while intentionally ignoring or omitting contradictory evidence. This fallacy involves selectively choosing only the most favorable information to support a claim, while disregarding any information that contradicts or undermines it.

Example 2: A politician claims that the economy is thriving, citing only the positive growth in certain industries, while ignoring the rising unemployment rates and declining wages in other sectors.

Explanation: Cherry picking is a fallacy because it presents an incomplete and biased picture of the evidence, creating a misleading narrative that supports a predetermined conclusion. By ignoring contradictory evidence, cherry picking distorts the truth and undermines the validity of an argument.

Alternative names: Selective evidence, confirmation bias, one-sided argument, slanted evidence.

20. Misleading Averages

Latin: Argumentum ad Mediocris Deceptivum, "argument to deceptive media"

Using statistical averages in a way that misleads the audience about the actual distribution of data.

Misleading Averages, or “Fallacy of Average,” is a logical fallacy that occurs when someone presents an average as a representative value, without considering the distribution of the data or the context. This fallacy involves using an average to make a claim or generalization, while ignoring the fact that the average may not accurately represent the typical value or experience.

Faulty Evidence Type: Source

These fallacies manipulate credibility by appealing to false authorities, leveraging popular opinion, or presenting biased sources as definitive proof. This can mislead the audience by relying on perceived authority or consensus rather than solid evidence.

21. Appeal to Authority

Latin 1: argumentum ad verecundiam, "argument to respect" or "appeal to reverence" Latin 2: Ipse Dixit, "He himself said it"

With the appeal to authority fallacy, you use an authority you believe as the argument. The problem is that experts are not always right, therefore you should refer to the authority’s argument. In a world where both good and bad authorities can be right, or wrong, about any conclusion, you need to evaluate the

Good authority example,

“The CDC says vaccines do not cause autism.”

Most of us consider the CDC to be a great authority. The problem is that if one believes vaccines cause autism, they may accept this good authority, but they may not. If they don’t, you’ll have to refer them to the CDC justification for their conclusion.

Bad authority example,

“Alex Jones says the government is making people gay, by what they put in the water.”

It’s tempting to simply throwback an ad hominem attack,

“That person is a complete idiot and you should not listen to them ever!”

However, a better reply might be,

“Can you provide me with the argument or evidence the authority used to come up with their conclusion?”

When confronted with stupid, you have to reply by advancing the conversation if you wish to convert stupid to smart.

22. Bandwagon

Latin: ad populum, "to the people"

Assuming something is true because many people believe it or do it. It appeals to our desire to fit in and be part of the crowd, but popularity doesn’t guarantee truth or effectiveness. For example:

“Everyone knows this product is the best!”

Or, pressuring someone to agree because everyone else is. For example:

“Get on board, everyone else is doing it!”

Note: Just because many people believe or do something, it doesn’t necessarily make it true or right. Critical thinking and evidence-based reasoning should guide our decisions, rather than following the crowd or conforming to popular opinion.

Strategy IV: Linguistic Trickery

Use word trickery to deceive them. Linguistic Trickery uses ambiguous or misleading language to deceive. This includes equivocation, amphiboly, and category errors, which exploit language to obscure the truth and confuse the audience.

23. Equivocation

Latin: argumentum ad aequivocationem, "argument to equivocation"

Using a term with multiple meanings without clarifying which one is intended. This fallacy occurs when someone uses a term or phrase with multiple meanings in an argument, switching between different meanings without clarifying which one is intended, in order to deceive, confuse, or mislead others.

Example 1:

“The law should be fair to everyone. Speeding is illegal, so everyone who speeds is unfair.”

In this example, “fair” has two meanings. In the first sentence, it refers to justice and equal treatment. In the second sentence, it’s used more loosely to mean “considerate” or “following the rules.” By switching the meaning of “fair,” the argument creates a false connection between speeding and unfairness.

Example 2:

“Nothing is perfect. Therefore, we shouldn’t strive for perfection in our work.”

In this example, the word “nothing” is used with two different meanings:

- “Nothing” (as in, “not a single thing”) is perfect.

- We shouldn’t strive for “perfection” (as in, “flawlessness or excellence”) in our work.

The argument equivocates between these two meanings, creating a misleading and fallacious conclusion.

Example 3:

A politician might say,

“I have the right to speak my mind,”

using the term “right” to imply both a moral entitlement and a legal permission, even though the contexts may differ significantly. Here, the politician uses the ambiguity of the word “right” to conflate different meanings, creating confusion and potentially misleading the audience about the nature of their entitlement or permission.

Note: Equivocation can be a subtle and sneaky fallacy, relying on ambiguity and context-switching to deceive. Critical thinkers must be aware of language nuances and demand clarity in arguments to avoid being misled.

24. Amphiboly

Latin: argumentum ad amphiboliam, "argument to amphiboly"

The “Amphiboly” fallacy occurs when an argument is based on a sentence or phrase that is grammatically ambiguous and can be interpreted in multiple ways. This ambiguity leads to confusion and misinterpretation, often allowing the arguer to take advantage of the unclear language. It’s the using of a sentence or phrase with multiple possible meanings without clarifying which one is intended.

The “Amphiboly” fallacy occurs when an argument is based on a sentence or phrase that is grammatically ambiguous and can be interpreted in multiple ways. This ambiguity leads to confusion and misinterpretation, often allowing the arguer to take advantage of the unclear language. It’s the using of a sentence or phrase with multiple possible meanings without clarifying which one is intended.

Example 1:

“I saw my neighbor with a telescope last night.”

This sentence is grammatically correct but ambiguous. It could mean:

- The neighbor was looking through the telescope.

- The neighbor was in possession of the telescope (but not necessarily using it).

Without additional context, the listener might interpret the sentence in a specific way that the speaker intends (e.g., implying the neighbor was spying), even though the sentence itself allows for other interpretations.

Example 2:

A headline might read,

“Police help dog bite victim.”

This can be interpreted as either the police helping a dog bite a victim or the police helping a victim who was bitten by a dog.

Example 3:

Consider the brain teaser question:

“Which 3 numbers give the same result whether multiplied or added?”

This question can be interpreted in multiple ways due to its ambiguous phrasing:

-

Correct Interpretation: Which three distinct numbers, when added together and when multiplied together, give the same result?

- Answer: 1, 2, and 3

- Calculation:

- Addition: 1 + 2 + 3 = 6

- Multiplication: 1 × 2 × 3 = 6

-

Misleading Interpretation: Which single number repeated three times gives the same result when added and multiplied?

- Misleading Answer: 2

- Calculation:

- Addition: 2 + 2 = 4

- Multiplication: 2 × 2 = 4

By clearly defining and understanding the intended meaning, we can avoid the pitfalls of amphiboly and improve our critical thinking and communication skills.

25. Category Error

Latin: argumentum ad categoriam, "argument to category"

The “Category Error” fallacy occurs when an attribute is incorrectly assigned to something that does not belong to that category, leading to confusion and misunderstanding. This fallacy involves treating a concept as if it belongs to a different category than it actually does. It is the attributing of a property or characteristic to something it doesn’t possess.

“He’s a good hammer, but he’s not very smart.”

26. Semantic Infiltration

Latin: argumentum ad infiltrationem semanticam, "argument to semantic infiltration"

Redefining a word or symbol negatively to change its connotation and influence perception. For example, redefining “liberal” as a derogatory term or appropriating symbols like the American flag to signify only a particular group. This tactic manipulates language to sway opinions and can create bias or prejudice by changing the emotional response associated with the term or symbol.

Example 1: Redefining the term “liberal” to imply something derogatory, like “weak” or “unpatriotic,” in political discourse.

Example 2: Original meaning: “Freedom of speech” refers to the right to express one’s opinions without government censorship.

Redefinition: “Freedom of speech” means the right to say anything without facing criticism or consequences (including hate speech, harassment, or defamation).

In this example, the original meaning is subtly altered to justify harmful or unethical behavior, making it difficult to address the issue without being accused of restricting “freedom of speech”.

Example 3: A political group using the American flag as their sole symbol, implying that their ideology is the only true form of patriotism.

Note: Semantic infiltration can be a sneaky fallacy, as it often involves gradual or subtle changes in meaning. Critical thinkers must be aware of the original definitions and context to recognize when semantic infiltration is occurring, and challenge the redefinition to maintain clarity and honesty in arguments.

Conclusion

Logical fallacies avoid discussing the issue directly usually because the person using the fallacy either does not know a valid argument, or they do not really wish to discuss it. People frequently do not wish to discuss issues they want to believe. Sometimes it’s easier to follow feelings or emotions.

The fact that someone uses a logical fallacy does not mean they’re wrong about the argument, it just means they have yet to make a valid argument. You can respond to logical fallacies by pointing them out and asking for another argument. Or, even better, if you know a valid argument that supports the other side, then point out the logical fallacy and give them the better argument and then discuss why you believe one valid argument over another. In essence, you hold a mini-debate with yourself.

For each issue that interests you, try to understand the valid arguments on both sides. When an issue has valid arguments on both sides, it’s good to know because going into a discussion, you already know where both sides will land and can better watch for logical fallacies.

2 thoughts on “Logical Fallacies Overview”

Hi Mike,

Just wanted you to know that I’ve linked to this topic on my blog: https://jesthinking.com/critical-thinking/

No back-link sought.

Thanks Wes. You are a good friend. I miss you being at the office and us diving into Delphi coding strategies!