By Chapter or Topic: All > Anchors > People > Docs > Touchstones > New Looks > History > Pre-Sumer

PRE-SUMER COGNITION: Did writing or even agrian civilizations start before Sumer? This timeline presents possible evidence for pre-Sumer advanced thinking including early human cooperation, settlement, and the development of culture. In “30 Philosophers: A New Look at Timeless Ideas,” I speculate about pre-Sumer civilizations, writing, and possible oral philosophical traditions going back 10 or 20 thousand years and potentially back to the cognitive revolution 50,000 years ago. I ask readers to keep an open mind as archealogists uncover the past. For example, the metropolis of the City of Catalhoyuk, circa 7100 BCE, is from more than 9,000 years ago! It was “rediscovered” in 1958 with the work of James Mellaart. What other socities or civilizations are underground right now awaiting discovery.

In the book, while I do present solid evidence for writing going back at least 6,000 years, I also speculate about it this way: “My personal conjecture, though speculative, is that writing emerged much earlier, potentially appearing multiple times between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago.” A bit later I write: “The earliest known advanced writing system is cuneiform dating back to about 3100 BCE (about 5100 years ago). Before this I’m sure many humans had advanced ideas that were spread using oral tradition. It’s likely some included some form of writing or drawings to facilitate teaching. It’s plausible some of them, at times, attempted to draw illustrations in dirt, on animal skin, wood, or stone. Perhaps some even made copies and distributed them. Unfortunately, none survived the test of time. These ideas and records were lost to time. I know, speculative, but this is a philosophy book.”

30 Philosophers Timeline: Pre-Sumer

The Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania stands as a testament to early human ingenuity and foresight, illustrating a rudimentary form of organizational behavior that predates modern civilization. Utilized extensively over two million years, the site functioned akin to a “factory,” where early humans systematically crafted a variety of stone tools. They strategically selected specific locations that optimized their tool-making efforts. This specialization of space for specific activities suggests a significant cognitive leap—recognizing the efficiency of designated work areas. Such spatial organization reflects the emergence of complex thinking, where early humans not only made tools but also thought strategically about where to make them, hinting at the early development of proto-civilizational structures.

Analysis: Interestingly, remarkably few human remains have been directly associated with the primary tool-making areas. This separation implies that while the site was pivotal for tool production, other aspects of daily life, such as habitation and burial practices, occurred elsewhere. The diverse array of tools found at Olduvai, from simple Oldowan choppers to more advanced Acheulean hand axes, marks significant milestones in technological advancement. The absence of human remains, coupled with the diversity of artifacts, provides crucial insights into the early human capacity for planning, foresight, and possibly, social stratification.

Found in central India, these cupules (circular hollows on rock surfaces) are among the earliest known forms of rock art. They were likely created by a species like Homo erectus or Homo heidelbergensis and not Homo sapiens. Homo sapiens are not known to be in India until around 40,000 years ago. Homo erectus is known in India as early as 1.7 million years ago and Homo heidelbergensis around 300,000 years ago. If Homo heidelbergensis is confirmed, that moves the evolution of symbolic thought back to before 700,000 years ago. If Homo erectus is confirmed, that moves it back to well before 2 million years ago.

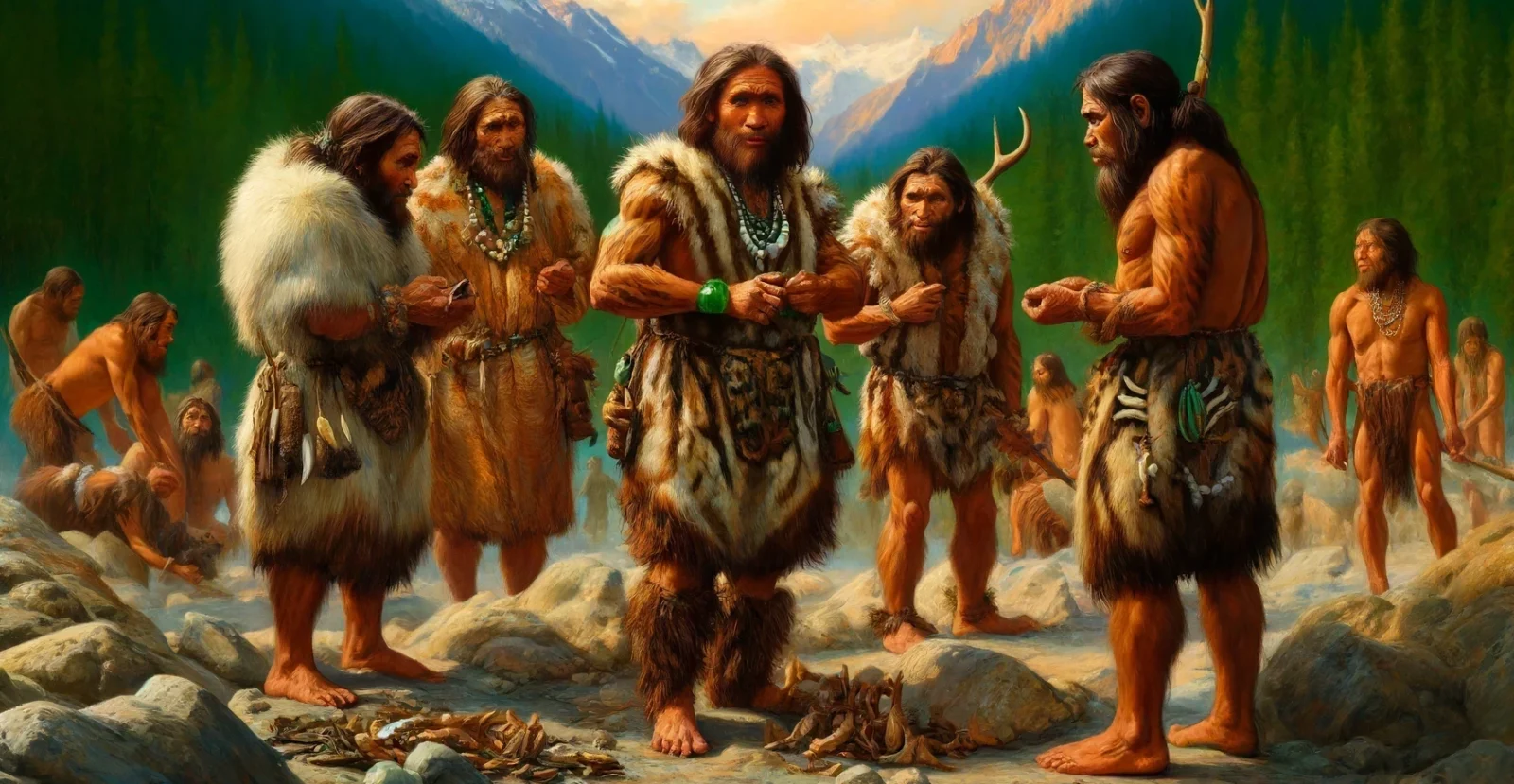

Earliest known seasonal settlement in the Africa/Middle East zone: In the diverse and rich landscapes of what is now South Africa, the Klasies River Caves served as a vital seasonal haven for early modern humans.

Positioned strategically along the coast, these caves were revisited across generations, suggesting a shared understanding among different groups about the benefits of this location. The community constructed simple yet effective shelters from branches and animal hides just outside the cave entrances, creating a setup that supported daily activities such as tool crafting, hide preparation, and communal cooking over open fires.

This pattern of seasonal settlement allowed for the efficient exploitation of local resources, minimizing the need for constant movement and enabling a more sustainable living arrangement. It fostered not only survival but a thriving community life where knowledge, skills, and social bonds were developed and strengthened.

The archaeological remains and artifacts from the Klasies River Caves—ranging from sophisticated stone tools to evidence of hearths and human remains—illustrate a complex social structure that predates agricultural societies. These findings highlight the ability of early humans to adapt to their environment through cooperative behaviors and strategic planning, showcasing a level of communal life and environmental management that speaks to the enduring human spirit and intellectual vigor comparable to that of contemporary societies. This site provides a profound glimpse into one of humanity’s earliest known attempts at semi-permanent living, underscoring the sophisticated social dynamics that underpinned pre-agrarian human settlements.

Imagined Image: The image of the semi-nomadic people of South Africa depicts a group of up to 50 individuals congregating here around 100,000 years ago, establishing a semi-permanent settlement that utilized the natural shelter provided by the caves and the abundant resources of the surrounding area.

.

Circa 76,000 BCE someone in Africa, perhaps the child’s parents, carefully prepared a human child aged about three years old for burial. They dug a circular pit at the entrance to a cave (likely their cave), placed the child in the hole on his or her right side with knees drawn toward the chest.

After proper analysis of the surrounding soil and the decomposition that has taken place in the pit over the years, the archaeologists believe the child, now nicknamed Mtoto, was intentionally buried shortly after death.

Denisovan: This bracelet dates from 70,000 to 40,000 BCE. It was discovered inside the Denisova Cave beside ancient human remains. The Denisova Cave is a cave located in Siberia, Russia. Other cave finds include woolly mammoth and woolly rhino bones. Scientists say there is evidence that the bracelet’s maker used a drill. This is the earliest known example of advanced drilling in the world.

Head of the museum Irina Salnikova said: ‘The skills of its creator were perfect. Initially we thought that it was made by Neanderthals or modern humans, but it turned out that the master was Denisovan.” This has led to speculation that these earliest humans, Denisovans, were more technologically advanced than previously thought. If true, it might be that the Denisovans were more skilled than Homo sapiens and Neanderthals of the time.

Like Neanderthal DNA, Denisovan DNA exists in modern humans. Non-African East Asians and Europeans have about 2% Neanderthal DNA. Modern Melanesians derived about 5% of their DNA from Denisovans.

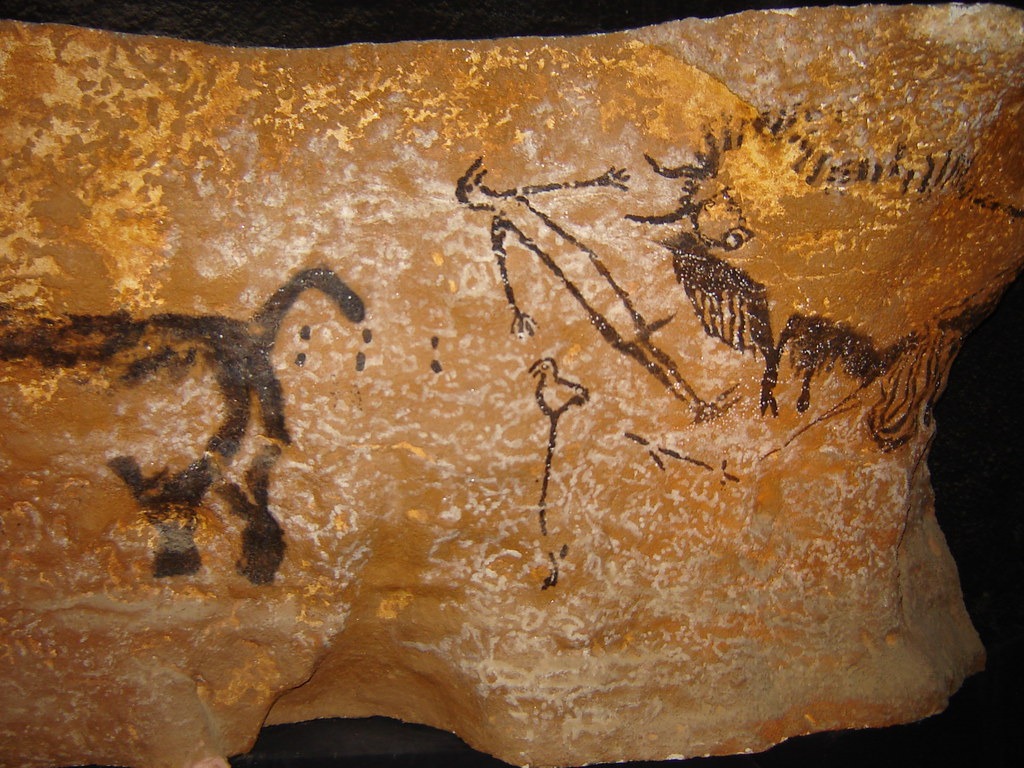

It’s clear: neanderthals created art. The discovery of cave paintings in Spain, dated to over 64,000 years ago, marked a profound shift in our understanding of Neanderthals. Found in sites such as La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Ardales, these artworks — comprising abstract symbols, geometric patterns, and hand stencils — are attributed to Neanderthals, predating the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe. This corrected the longstanding perception that Neanderthals lacked symbolic thought and artistic expression.

The presence of these ancient artworks, along with evidence of personal ornaments like decorated shells, suggests that Neanderthals engaged in behaviors once thought exclusive to modern humans. This includes the creation of art and the use of symbolic communication, indicating a level of cognitive sophistication and cultural complexity previously unrecognized. These findings not only expand our understanding of Neanderthal capabilities but also blur the lines between them and our own ancestors, highlighting a shared capacity for creativity and symbolic thinking in the human lineage.

Cognitive Revolution

50,000 BCE – 70,000 BCE. Population range: 500,000 to 2.5 million.

Given the uncertainties and lack of direct data, the following are speculative estimates.

- Africa-Middle East: 50-60% or 600,000 to 1 million people

Africa, being the origin of modern humans, likely had the highest population density at this time, particularly in Sub-Saharan regions which were more conducive to human habitation due to their climate and available resources. - Asia: 40% or 200,000 to 400,000 people

- Europe-Mediterranean: 10% or 50,000 to 100,000 people

- The Americas: 0.

- Oceana-Australasia: 1% or 10,000 to 15,000 people

The initial colonization of Australia around 50,000 BCE by modern humans involved small, isolated groups who managed to navigate sea crossings, leading to a very low initial population density. The rest of the remote islands of Oceania were among the last to be reached by humans.

A Shared Earth! Neanderthals-Hobbits-Flourensis

Around this time, Homo sapiens shared the Earth with other hominin species. Neanderthals were still widespread in Europe and parts of western Asia. In Asia, particularly on the islands of Indonesia, Homo floresiensis, often referred to as the “Hobbit” due to their diminutive stature, survived until about 50,000 years ago. Additionally, Denisovans, a less visually documented but genetically distinct group, also roamed Eurasia, leaving behind a genetic legacy that persists in modern humans, particularly among populations in Melanesia.

The sea offers tremendous resources and stability. The rising and receding oceans continue to destroy the homes of many. How many unknown cultures in our vast history thrived on the coast for millennia?

The site discovered off the coast of Cuba, also known as the “Cuban Underwater Pyramids,” includes pyramid-like structures and other geometric formations identified using sonar and underwater robots by the research team led by Paulina Zelitsky and Paul Weinzweig. This site, submerged at a depth of around 650 meters, has sparked debate and speculation about its origins, with some suggesting it could be remnants of an ancient civilization dating back more than 50,000 years, while others argue it might be a natural geological formation. Further research is needed to uncover the true nature of these intriguing structures.

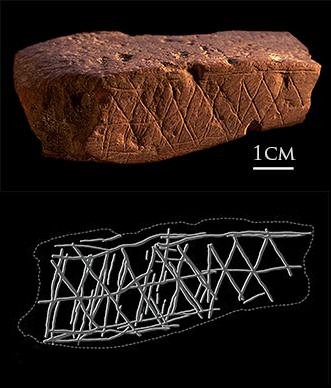

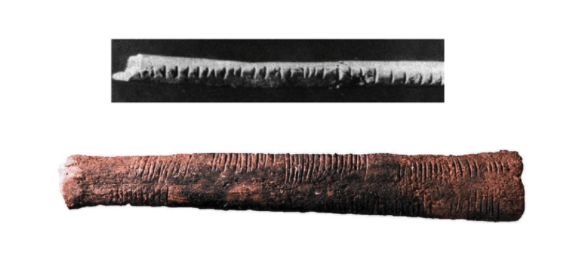

The Lebombo Bone is one of the oldest known mathematical artifacts in human history. This ancient tool is a baboon fibula with 29 distinct notches carved into it. It was discovered in the Lebombo Mountains between South Africa and Swaziland. It was initially dated to approximately 35,000 years, but 24 radiocarbon tests since date it back about 44,000 years.

The Lebombo Bone was potentially used as a lunar phase counter or a simple tally stick. The series of notches may represent a lunar calendar, which would imply that early humans were tracking lunar phases for either ritualistic purposes or as a practical method for keeping time, possibly related to menstrual cycles or seasonal changes.

This artifact belongs to the Middle Stone Age, a period characterized by the development of more advanced stone tool technologies and the emergence of modern human behavior, including symbolic thought and perhaps early forms of arithmetic. The Lebombo Bone suggests that early humans engaged in complex thinking and had the capacity for abstract thought and planning.

The discovery of the Lebombo Bone and similar artifacts underscores the cognitive capabilities of early humans and their ability to use numerical concepts long before the development of written language or formal systems of numeration. This artifact, along with others like the Ishango Bone from Central Africa, indicates that the concept of counting and numerical recording was a part of human culture across different regions of Africa tens of thousands of years ago.

Earliest known seasonal settlement in the European Mediterean zone: Nestled in the Argolid region of the Peloponnese in Greece, the Franchthi Cave offers a unique window into the lives of early Europeans spanning from the Upper Paleolithic through the Mesolithic and into the Neolithic periods. For over 23,000 years, from about 20,000 BCE to 3,000 BCE, this cave served as a seasonal hub for prehistoric communities.

The strategic coastal location of the Franchthi Cave allowed early humans to exploit both marine and terrestrial resources effectively. The abundance of marine shells and fish bones found within the cave layers suggests that these groups were highly adept at fishing and shellfish gathering, activities that likely formed a significant part of their subsistence strategy during their stays.

As seasons turned, these early inhabitants would have utilized the cave as a base from which to conduct their hunting and gathering activities. Over millennia, the evidence shows a gradual shift from reliance on wild resources to the introduction of domesticated plants and animals, signaling the start of agricultural practices in the region.

This transition marks Franchthi Cave not just as a site of temporary habitation but as a pivotal location where significant cultural and technological transformations occurred. The cave’s extensive use and the layers of habitation offer profound insights into the evolutionary journey of human societies in the Mediterranean, showcasing how a simple seasonal settlement could eventually evolve into a cornerstone of early agrarian life.

Franchthi Cave thus represents one of the earliest known seasonal settlements in the European-Mediterranean zone, providing invaluable lessons on the adaptability and innovation of early human communities in the face of changing environmental and social landscapes.

Imagined image: This image portrays a seasonal settlement at Franchthi Cave around 10,000 BCE, where early humans utilized natural materials to construct temporary shelters nestled within a lush landscape. Central hearth areas serve as communal hubs for cooking and social gatherings, illustrating the strategic use of space and resources by these early inhabitants. The arrangement of shelters around the cave entrance highlights their reliance on the natural environment for survival and community activities.

The Mezhyrich community thrived in Ukraine, living in huts built from mammoth bones. These resourceful people used mammoth skulls, tusks, and bones to construct shelters covered with animal skins. They engaged in daily activities such as cooking, tool-making, and socializing, showcasing a harmonious, bustling life. The nearby rivers provided resources and sustenance, while their sophisticated structures indicated advanced social organization and cooperation.

Since grain is easy to grow, does this suggest agriculture might have started a few thousand years earlier? Under study, but the discovery of bread-making from around 14,000 years ago indeed suggests that humans were experimenting with grains before the widespread adoption of agriculture, which is traditionally dated to about 12,000 years ago with the Neolithic Revolution.

In the shadow of history, nestled within the Black Desert of northeastern Jordan, lies the cradle of one of humanity’s most enduring culinary and cultural achievements: the invention of bread. Around 14,000 years ago, long before the dawn of agriculture and the domestication of cereal grains, the Natufian hunter-gatherers embarked on a gastronomic adventure that would forever change the course of human society.

Located in modern-day Syria, this is an important site because of the evidence demonstrating a likely pattern from hunter-gatherer to farming. It provides evidence of one of the earliest known villages. The leading interpretation is that they were settled in the area and practiced hunting and gathering before about 11,500 BCE. Around 11,500 BCE there is clear evidence of farming. While it’s likely they still hunted and perhaps gathered, it was around this time at least part of their food was from farming. This site provides insights into the transition from nomadic to settled life, showcasing early domestication of plants and permanent structures.

The Neolithic Revolution is the earliest known Agricultural Revolution. It is very likely that humans practiced forms of agriculture earlier. How much earlier? Well, without evidence, we are guessing. For convenience, anthropologists label humans as hunter-gatherers prior to the Neolithic Revolution. The fact is that the current theory states that agriculture started magically all around the world circa 9,700 BCE. I think it is much more likely this is simply the earliest farming we have yet to discover and will likely push this date back further and further over time.

The Neolithic revolution is the belief in a wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an increasingly large population possible. These settled communities permitted humans to observe and experiment with plants, learning how they grew and developed. This new knowledge led to the domestication of plants. A stable lifestyle led to more leisure time and more time to think about things which led to what we would call civilization today. Only the most sturdy of structures from this time period survived the test of time.

Located in modern-day Turkey, Göbekli Tepe is one of the world’s oldest known temples. This site features massive carved stones and complex architectural structures that predate Stonehenge by some 6,000 years. The sophistication and scale of Göbekli Tepe suggest that the community was able to coordinate large-scale projects, indicating a high level of social organization and spiritual or communal life. Without evidence of permanent residential structures from this site, these people were more likely hunter-gatherers that stuck to the area, and not farmers.

Earliest known permanent settlement in the Africa/Middle East zone.

Jericho, located in the West Bank, Palestinian Territories, stands as one of the earliest known permanent settlements in the Africa/Middle East zone, with continuous habitation dating back to at least the 9th millennium BCE. Situated near an oasis in the Jordan Valley, Jericho’s strategic location provided access to vital water sources, facilitating agriculture and sustaining human settlement.

Permanent Settlement Note: This early permanence challenges traditional notions of settlement patterns, showcasing the importance of water in the establishment of communities. It’s worth noting that while Jericho is among the earliest known permanent settlements, there may be even earlier settlements nestled along lakeshores or rivers, but their discovery is hindered by the very element that made them attractive to ancient peoples: water.

The earliest known use of plaster dates back to around 9000 BCE, with evidence from the ancient site of Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey. Here, Neolithic inhabitants utilized plaster made from lime to coat the floors, walls, and even ceilings of their mud-brick houses. This early application of plaster represents a significant technological innovation, indicating a sophisticated understanding of construction materials and their protective and aesthetic properties. The use of plaster enhanced the durability and appearance of architectural structures and had practical health benefits, such as preventing infestations and regulating indoor climates.

In the lush, fertile lands of the Yangtze River Valley in ancient China, early inhabitants achieved a milestone that would revolutionize human society: the domestication of rice. Around 8,000 BCE, these innovative communities began to cultivate wild rice, laying the groundwork for sedentary agriculture and complex civilizations. This agricultural breakthrough not only provided a stable food source but also spurred social and technological advancements, leading to the rise of sophisticated cultures and the eventual emergence of the Chinese civilization, one of the world’s oldest continuous cultures.

Possible lost city off Japan: Discovered in 1985 off the coast of Yonaguni, Japan, it has captivated archaeologists, geologists, and conspiracy theorists alike. Characterized by its monolithic, terraced structures, this submerged rock formation resembles architectural craftsmanship that some suggest could date back to around 8000 BCE, a time when global sea levels were significantly lower. This date remains highly speculative, as definitive scientific consensus on the monument’s origins—natural or man-made—has yet to be established.

The debate hinges on the monument’s peculiar features, such as precise angles and straight edges that evoke images of human-made pyramids and temples. Proponents of the man-made theory argue that these features are too structured to be products of natural geological processes and suggest a lost civilization’s handiwork.

The Ain Ghazal statues, dating back to around 7200 BCE, are among the earliest known examples of human figures crafted from plaster, highlighting an advanced use of materials in the Neolithic period. This technique involved applying plaster, made from lime and powdered limestone, over a core of reeds and twine to create lifelike statues with detailed facial features and expressive eyes made from bitumen. The use of plaster for such artistic and possibly ritualistic purposes at Ain Ghazal predates many other known uses of the material in sculpture. While plaster had been used in simple construction and repair tasks even earlier, the sophisticated application at Ain Ghazal marks a significant development in the artistic capabilities of Neolithic societies.

The city of Çatalhöyük was a very large Neolithic city in the southern Anatolia peninsula in modern day Turkey. The population of 5,000 to 10,000 lived in mudbrick buildings. Some of the larger buildings have ornate murals. A painting of the village, with the twin mountain peaks in the background is frequently cited as the world’s oldest map, and the first landscape painting.

No sidewalks nor streets were used between the dwellings. The clustered honeycomb-like maze of dwellings were accessed by holes in the ceiling and by doors on the side of houses. The doors were accessed by ladders and stairs. The rooftops were effectively streets. I can imagine on good whether days the rooftop of the massive honeycomb building was similar to a Roman forum some 5,000 years in the future–a place to meet, socialize, and perform business.

Potential earliest writing in Asian zone: the Oracle Bone Script, circa 1250 BCE is oldest confirmed.

These symbols which are radiocarbon dated to the 7th millennium BCE have similarities to the late 2nd millennium BCE oracle bone script. Put this writing in the MAYBE column. Scientists are still going through a process to verify this claim. If we can discover some intermediate links, yes, more missing links, we can firm up these symbols as early writing. They were discovered in 2003 on tortoise shells found in 24 Neolithic graves excavated in Jiahu, Henan province, northern China.

The Fuente Magna Bowl, discovered in 1950 near Lake Titicaca, Bolivia, is a large stone vessel with intricate carvings. Unearthed by a local farmer, the bowl was later donated to a small local museum and eventually transferred to the Museum of Precious Metals in La Paz. The bowl features engravings that some claim resemble ancient Sumerian cuneiform and other proto-scripts. This artifact’s intricate carvings have sparked significant interest due to their apparent similarity to writing systems used thousands of miles away in ancient Mesopotamia.

It might be a modern forgery, but if not, the Fuente Magna Bowl is significant because it might point to a Sumerian-South America connection or to earlier proto-writing. Experts like Dr. Clyde Ahmed Winters have proposed that the inscriptions are Proto-Sumerian, suggesting possible ancient transoceanic contact. However, many scholars are skeptical, citing inconsistencies in the script and questioning the bowl’s provenance. Some suggest that the markings might hint at an earlier form of writing, indicating a longer and more complex path to the development of written language than currently understood. This possibility could have profound implications, suggesting that the origins of writing might be more widespread and interconnected than previously thought.

End of timeline. Review…

By Chapter or Topic: All > Anchors > People > Docs > Touchstones > New Looks > History > Pre-Sumer