Evolution TL: March to Life > Evolution > Great Apes > Human > Consciousness > All to Us

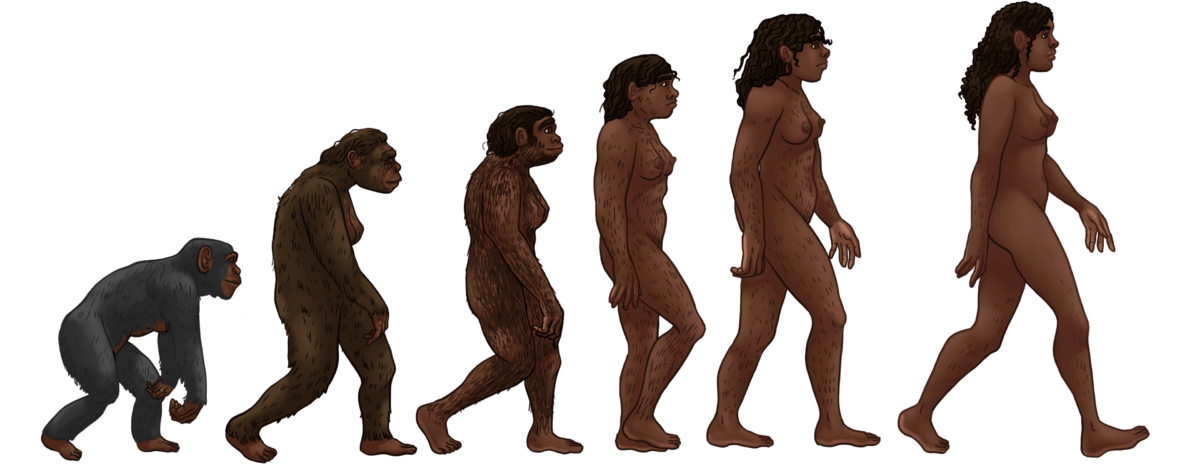

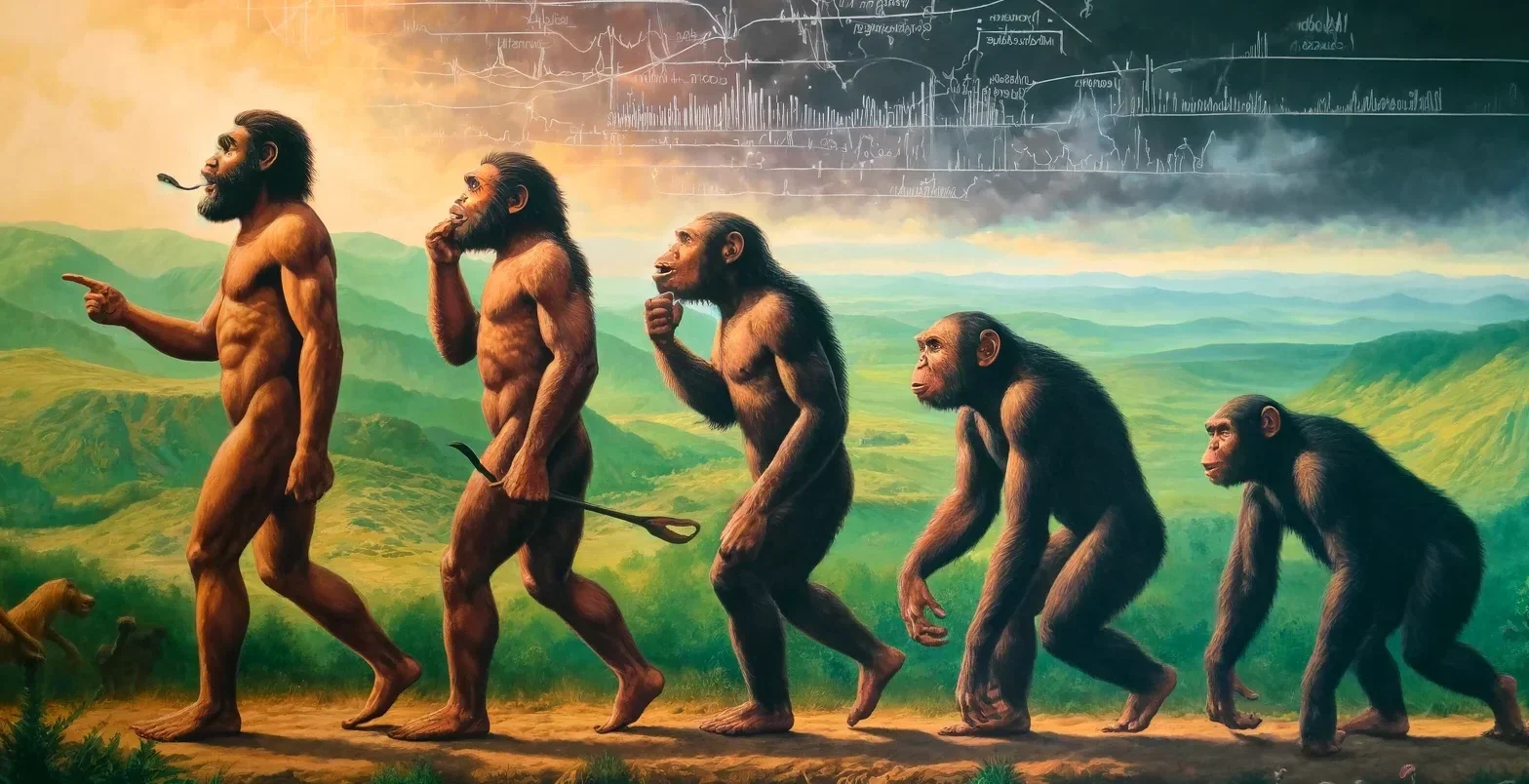

Human Evolution: This timeline picks up our story with the evolution of Homo sapiens within the greater Great Ape story. Explore Hominids to explore our greater Great Ape story; explore hominins to explore our story after the chimp-human split.

- Hominidae Family: The Great Apes (all hominids and hominins including genus Homo).

- Hominid: Us=direct ancestor from the Great Apes LCA to Homo habilis.

- Hominin: Us=direct ancestor back to CHLCA or genus Homo.

- Homo sapiens: our specific species.

Humans did not evolve from Chimpanzees, but both are the current evolution of a common ancestor. That common ancestor has yet to be identified and is sometimes referred to as the Chimpanzee–Human Last Common Ancestor (CHLCA). That ancestor lived in Africa about 7.5 million years ago, likely in East Africa or perhaps Central Africa. The genus that is perhaps the most likely for the CHLCA is Sahelanthropus. While much of Africa today features arid deserts, Western Africa and at least parts of Central Africa and Eastern Africa were rainforests and tropical forests during this key time of early hominin evolution.

The descendants of CHLCA are known collectively as the Hominini tribe within the larger Hominidae family. Today this tribe includes only humans, the common chimpanzee, and bonobos. Did you notice that I said CHLCA is not part of the Hominini tribe? Interestingly, scientists so far have excluded the ultimate founder of the Hominini tribe. Tribes are defined by common characteristics and because we have yet to find a CHLCA, they are left out. Since all known descendants of CHLCA, living and extinct, have the common characteristics that define the Hominini tribe, so did CHLCA. Well, that’s what I think at least. For more on why the simplest explanation gets this kind of weight in analysis, check out my Occam’s Razor: Simplifying Complexity article.

CHLCA likely lived sometime between 5 and 13 million years ago, with 7.5 million years ago being a common educated estimate. Sahelanthropus tchadensis, and other later Hominini tribe descendants, supports estimates placing the CHLCA at about 7.5 million years ago. For example, Sahelanthropus tchadensis survived from 7 to 6 million years ago in Central Africa.

CHLCA candidate: Often considered one of the earliest potential hominins, Sahelanthropus tchadensis, best known from the “Toumai” skull found in Chad, exhibits features that suggest bipedalism but remains debated due to limited fossil evidence. With two human anatomical traits, small canine teeth, and a spinal cord hole in the cranium further forward (on the underside of the cranium), it is possible that they are the fist of our ancestors to walk upright. If not, they likely had an intermediate stride.

Survival: From about 7 to 6 MYA in Central Africa (a densely wooded rain forest at the time)

Size: 4′ to 4’6″ (a little taller than modern chimpanzees)

Brain Size: around 320 to 380 cm³ (speculative)

Brain to Body EQ: Unknown, but like similar to chimpanzees at 2.2 to 2.5 (humans=7.4 to 7.8)

Perhaps the first species below represents Sahelanthropus tchadensis:

CHLCA candidate: This genus includes Ardipithecus ramidus (like “Ardi”) and possibly earlier species like Ardipithecus kadabba. Ardipithecus shows a mix of bipedal traits and adaptations for climbing, reflecting a transitional form in human evolution.

In the verdant landscapes of Laetoli, Tanzania, beneath a layer of volcanic ash from a nearby eruption, a remarkable story is preserved. Dating back 3.66 million years, a series of footprints capture a fleeting moment in time when early hominins walked across the wet ash. These footprints, attributed to Australopithecus afarensis, represent one of the earliest known evidences of bipedal locomotion, a pivotal adaptation in human evolution. The prints reveal not just the mechanics of early human walking but also a snapshot of life in a world teeming with both challenges and opportunities. As these hominins moved through their environment, their upright strides marked a significant departure from their four-legged forebears, setting the stage for a journey that would eventually lead to us. The discovery of these footprints in 1976 by Mary Leakey and her team opened a window into our ancestral past, highlighting a critical step in our long, adaptive stride through history.

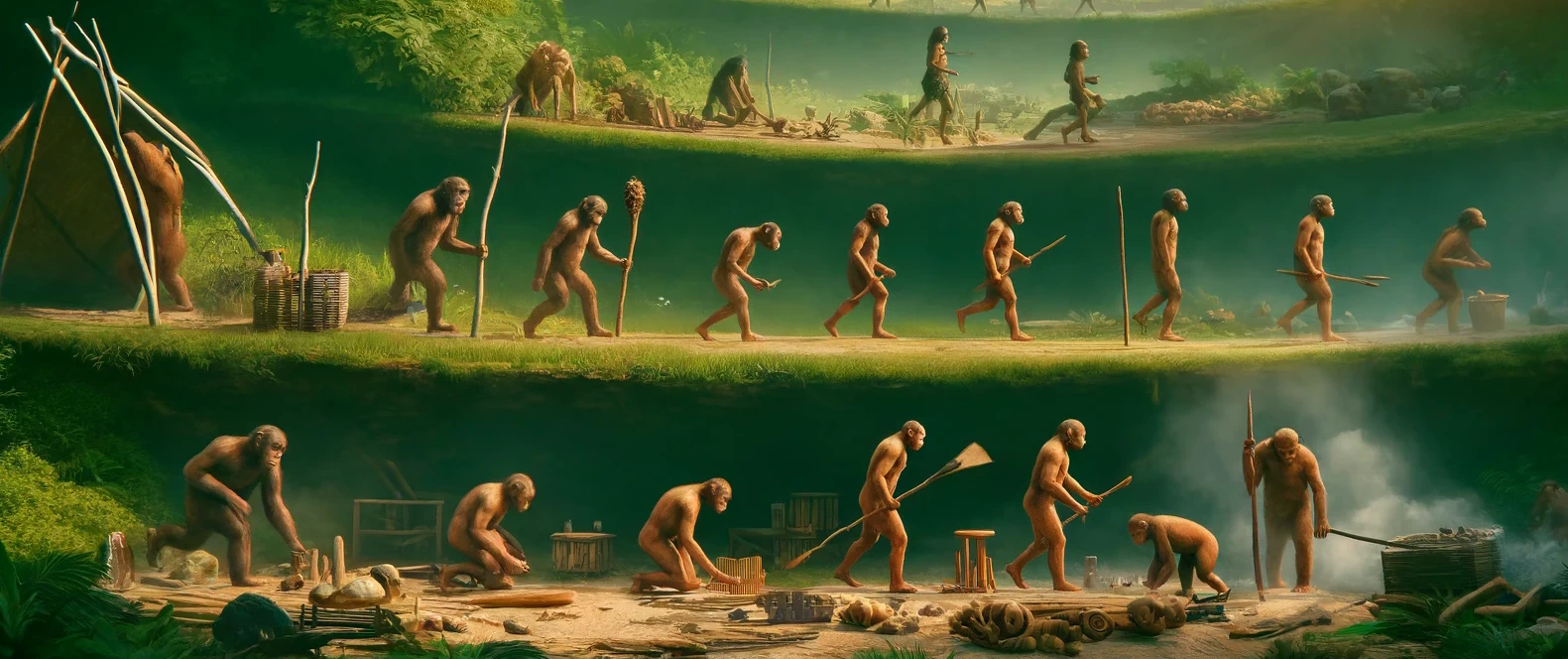

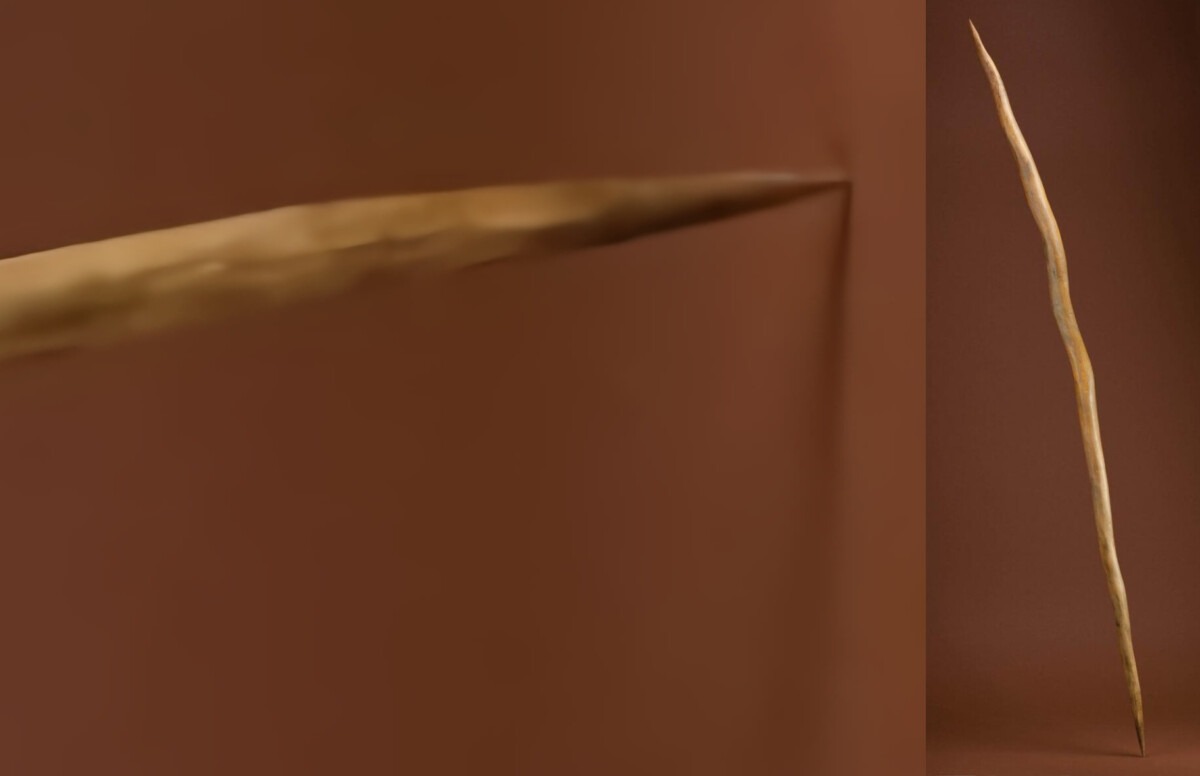

Simple wood tools starting with picking up a stick to poke at some out of reach fruit likely paralleled the use of stone tools. Wood tools for the most part did not survive the test of time. The earliest so far include advanced javelins form 400,000 years ago and a digging tool from 780,000 years ago.

Possible, but speculative, progression of wood tools:

By 3.4 mya: hand stick used for poking and defense. A hand stick could be used for poking to gather edible plants, digging small holes, or as a simple defensive tool against predators or rival groups as well as for hunting smaller prey. Chimpanzees today sharpen sticks and kill bushbabies so it’s reasonable to speculate that hominins have been doing similar things going back to at least 3.4 million years ago.

By 3.3 mya: walking stick used for protection and hunting. As early hominins began to traverse more varied terrains, the use of walking sticks could have emerged. These sticks, possibly sharpened at one end, could serve dual purposes: aiding in mobility over rough landscapes and as a rudimentary weapon for hunting small animals or defense.

By 2.6 mya: small sharpened sticks for detailed work. Coinciding with the development of Oldowan stone tools, which included flakes and cores, early humans could have crafted small, sharpened wooden sticks. These sticks would be useful for tasks requiring more precision, such as extracting termites from mounds, piercing to create simple garments from hides, or intricate food preparation like skewering.

By 1.76 mya: Spears and Digging Sticks: With the advent of Acheulean hand axes, there might have been the concurrent use of wooden spears, either fire-hardened or using stone tools to sharpen the tips. These would be essential for hunting larger animals at a distance. Similarly, robust digging sticks could be used for accessing water sources, tubers, or creating simple traps.

By 500,000 ya: Complex Wooden Constructs: By the time Middle Paleolithic tool cultures emerged, there could be more complex wooden constructions such as frames for shelters, more sophisticated spears, and possibly even simple rafts or paddles for navigating waters. The use of fire to harden and treat wood could enhance the durability and effectiveness of these tools.

By 300,000 ya: Hafted Tools and Advanced Spears: The use of adhesives and bindings to attach stone points to wooden shafts likely emerged, producing more effective hafted tools. This period may also see the refinement of spear technology, with better aerodynamics and durability for more effective hunting strategies.

By 200,000 ya: Ritual or Symbolic Wooden Structures: The potential for wooden objects to play a role in ritual or communal activities, such as totem poles or communal meeting structures, reflecting more complex social behaviors and spiritual beliefs.

The earliest known stone tools date back to at least 3.3 million years ago. They are identified by their purposeful flaking patterns, sharp edges, and location with other more identifiable artifacts or fossils. They are then verified with microscopic analysis confirming repetitive use.

Possible Stone-Tool Progression:

By 3.4 mya: Hammerstones, no modification, used for pounding seeds, nuts, or breaking bones.

By 3.3 mya: Lomekwi stone tools. Stone cores, rock flakes removed to reshape, narrow, or sharpen.

By 2.6 mya: Oldowan tools; first definite tools. Stone flakes with sharp edges would used for cutting meat, scraping hides, chopping plants, and wood whittling.

By 2.4 mya: Refinement of Oldowan tools, with more controlled flaking and sharper edges.

By 1.76 mya: Acheulean hand axes, iconic tools with a distinctive teardrop or oval shape for chopping wood, butchering animals, digging, and scraping.

By 1.76 mya: Larger cutting tools such as cleavers for butchering large animals, or heavy-duty scrapers for processing hides or wood.

By 500,000 ya: Middle Paleolithic tools, including pointed hand axes, side scrapers, knife-like tools, and awls for piercing.

By 300,000 ya: Diverse materials such as bone and antler start surviving the test of time. Earliest evidence of composite tools using multiple materials combined to produce tools with specific functions.

By 200,000 ya: Hafted tools, where stone tips are attached to wooden handles, significantly enhancing their effectiveness and range of use.

The dawn of collective learning can be traced back the oldest known stone tools, discovered at Lomekwi 3 in Kenya. The creation of these tools required more than just individual innovation; it involved the rudimentary form of collective learning, where knowledge of toolmaking was shared within groups. This early transmission of skills not only enhanced survival and adaptation but also marked the beginning of cultural accumulation—a fundamental characteristic that would define human societies.

Collective learning is the 6th threshold in Big History. While they place it at about 200,000 years ago, I recrafted it as Trasendental Intelligence and moved it back to 475,000 years. Collective learning, likely started with cultural transmission and the making of tools is a good example. If you agree, then collective learning moves back to at least 3.3 million years ago.

Slightly greater range of movement and precision: Around 2 to 3 million years ago, the evolution of the human thumb reached a pivotal point. Early hominins, such as Australopithecus and later Homo habilis, exhibited a thumb that was more similar to that of modern humans. This thumb was capable of a greater range of movement and precision, which was crucial for the development of advanced tool-making techniques. The ability to craft and use tools not only provided a survival advantage but also facilitated the development of culture and technology. The evolution of the human thumb is a key factor in the story of human evolution, highlighting the interplay between biological adaptation and cultural innovation.

This genus is more directly ancestral to humans and includes several species, such as Australopithecus afarensis (famously represented by “Lucy”), Australopithecus africanus, and others. Australopithecines show a greater commitment to bipedalism and have features more closely resembling modern humans, although they still retained some adaptations for climbing.

This genus is known for their true bipedalism, enhanced predator awareness, and facilitated tool use by freeing the hands. These hominins exhibited significant dental evolution, with smaller, less pronounced canines indicative of dietary changes and reduced aggression, suggesting more complex social interactions. Their brains, though only modestly larger than those of great apes, showed gradual increases in size, hinting at evolving cognitive abilities.

Survival: From about 4.2 to 2 MYA in Eastern and Southern Africa (in woodlands and grasslands)

Size: 3’6″ to 4’6″ (a bit taller than modern chimpanzees)

Brain Size: around 350 to 550 cm³ (speculative)

Brain to Body EQ: 2.5 to 3.5 (humans=7.4 to 7.8)

Species: Australopithecus anamensis (around 4.2 to 3.9 million years ago), Australopithecus afarensis (famous for the “Lucy” specimen, around 3.9 to 2.9 million years ago), and others.

Earliest Identified Human: Earlier hominins are “humanoid,” due to their human-like features, but the term “human” is reserved for species in the genus Homo. Homo habilis is the earliest known of these “early humans.”

First Earth Explorer: Known as the “handy man,” Homo habilis’s association with the earliest stone tools is evidence of unprecedented level of cognitive ability, including foresight, planning, and the ability to manipulate the environment in complex ways. They used stone tools as well as controlled fire. They were likely the first of “us” to explore most of the Earth. We know they evolved into at least 20 known species of which only Homo Sapiens survive today.

You can think of Homo habilis as a super smart chimp, a 55% smarter one.

Survival: From about 2.4 to 1.4 MYA in Eastern and Southern Africa (in woodlands and grasslands)

Size: 3’4″ to 4’5″ (a bit taller than modern chimpanzees)

Brain Size: around 510 to 600 cm³

Brain to Body EQ: 3.3 to 3.8 (humans=7.4 to 7.8)

The earliest containers were likely simple natural resources that early hominins stumbled upon and adapted for use. Starting possibly with Homo habilis around 2.0 million years ago, these early humans may have utilized large leaves, shells, or naturally hollowed-out pieces of wood as rudimentary containers. This usage marks an innovative step in early human technology, reflecting an understanding of natural resources for practical purposes.

As hominins evolved, particularly with the advent of Homo erectus, more sophisticated uses of materials likely developed. Homo erectus, known for their tool-making abilities, might have used animal hides to gather and carry items, gradually fashioning them into simple bags or slings. This represents a significant advancement in carrying technology, allowing for the transport of goods over greater distances and supporting more complex foraging strategies.

Before these developments, even earlier hominins may have employed static storage methods, such as piling resources like rocks or wood in designated locations, such as inside caves or on natural ledges. These caches would have served as communal collection points that group members could contribute to and draw from, reflecting early forms of community resource management.

Additionally, the use of vines or strong plant fibers to tie items together suggests the beginning of material manipulation for transport purposes, predating the knowledge of weaving but laying the groundwork for future technological innovations in container making.

Homo erectus is a direct ancestor of modern humans and represents a key point in human evolution where evidence of a truly omnivorous diet becomes clear, including the use of tools for hunting and processing both plant and animal foods. This species shows significant brain enlargement and other adaptations indicative of complex foraging and social behaviors.

Survival: From about 1.9 MYA to 50,000 years ago. Emerged in Eastern Africa, spread throughout Africa, Asia, and into Europe.

Size: 4’9″ to 6’1″

Brain Size: around 600 to 1,100 cm³

Brain to Body EQ: 3.3 to 3.8 (humans=7.4 to 7.8)

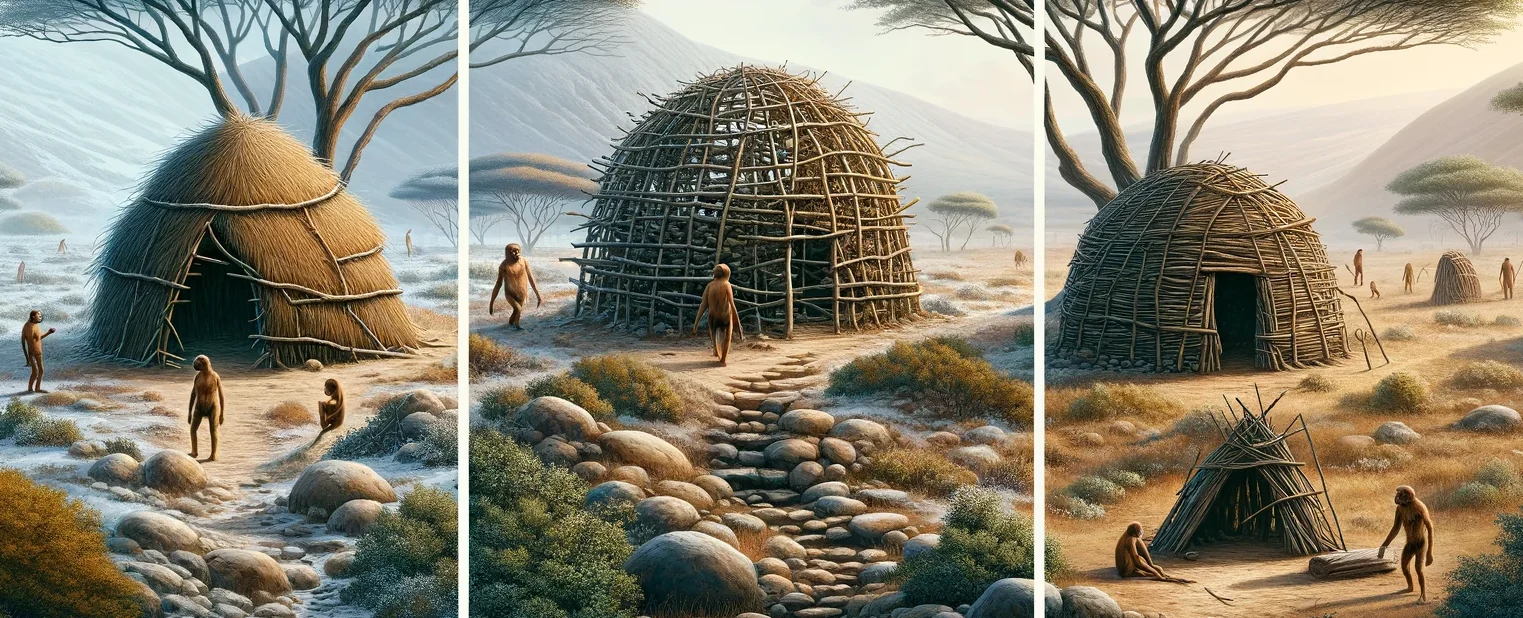

The origins of tent-like structures in human history remain shrouded in mystery, primarily due to the perishable materials involved and the lack of direct archaeological evidence. However, as Homo erectus appeared and spread into varied climates, their enhanced tool-making skills and control of fire likely necessitated and enabled the construction of more complex shelters. This period marks a significant point where early humans may have started to build the first tent-like structures using branches, leaves, and plant fibers to create semi-permanent shelters. The move into cooler environments would have increased the need for such innovations.

Before this timeframe, it’s possible Homo habilis created simple shelters. The emergence of Homo habilis and their use of simple stone tools opens a window of possibility. They might have used vines or branches to create rudimentary windbreaks or lean-tos for temporary protection from the elements.

Species: Likely Homo erectus, our direct ancestor. The footprints found in Ileret, Kenya represent the oldest undisputed evidence of hominins walking upright in an efficient manner characteristic of modern humans. Our style of upright walking, which Homo erectus appears to have shared, is energy-efficient and adapted for long distances. It involves a long stride with a spring-like mechanism in the arch of the foot. These particular footprints demonstrate a well-developed arch and a long stride, culminating in a propulsive toe-off similar to us.

By this period, Homo erectus set a precedent for the locomotion seen in future hominin species, including Homo heidelbergensis, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and even the shorter Homo floresiensis.

As Homo erectus roamed the expansive savannas, a significant evolutionary shift occurred in human ancestors: the reduction of body hair. This adaptation likely enhanced sweat-based cooling systems, crucial for surviving and thriving under the scorching sun during long hunts and foraging activities. While this change marked a general trend towards the hairiness levels observed in modern humans, variations persisted among individuals, reflecting a natural diversity similar to the range seen today. Some members of this early Homo population may have retained slightly more body hair, potentially offering better insulation in cooler climates or during seasonal changes.

Skin Color Variety: Each time a species of our genus Homo ancestors spread to new environments, the melanin mechanisms that all primates have kick in. The following is an imagined image of our ancestors in the various environments they spread into by 1.2 mya.

References

The Evolution of Human Hair and Its Role in Thermoregulation – https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/the-evolution-of-human-hair-and-its-role-in-thermoregulation

The Surprising Origins and Uses of Human Hair – https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-surprising-origins-and-uses-of-human-hair-29138876/

Hair | Anatomy – Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/hair-anatomy

The Role of Hair in Human Evolution – ScienceDirect: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248413000282

NSLCA Candidate: This ancient human species challenges traditional views by suggesting that some of our human ancestors bore a closer resemblance to modern humans than previously believed. Homo antecessor, which existed long before Homo sapiens and Homo heidelbergensis, displayed distinctly modern human-like features, including a flatter face and a more refined nose, indicative of significant evolutionary developments.

The concept that Homo antecessor may have had such advanced facial features suggests a complex evolutionary lineage that might revise our understanding of human morphology’s progression. These traits possibly facilitated enhanced social interactions and communication, reflecting a sophisticated level of behavioral adaptation.

To illustrate the uncertainty and the scope of scientific interpretation in paleoanthropology, consider the following artistic impressions. These images underscore the speculative nature of reconstructing ancient human appearances—while grounded in evidence, each representation involves a degree of conjecture.

Or even:

Or even:

Genus Homo: Rapid brain growth in our human ancestors started about 800,000 BCE. Now, by rapid brain growth we mean about 600,000 years! Larger complex brains helped early humans to survive. They interacted with each other and their surroundings in new and different ways.

Burned flint tools dated to circa 790,000 BCE were discovered at Gesher Benot Ya’aquov, Israel. Control of fire is one of the key traits of the genus Homo.

Around 700,000 years ago, the development of a human-like hyoid bone suggests early hominins may have begun transitioning from simple vocalizations to more structured speech.

This period marks a critical evolutionary point for Homo heidelbergensis, whose anatomical adaptations for speech, coupled with advanced tool use and complex social structures, indicate possible use of rudimentary language. Earlier hominins like Homo erectus also showed signs of vocal communication, but whether this included structured language remains uncertain. This era highlights the beginnings of speech, setting the stage for the sophisticated linguistic capabilities of later hominins.

Full emotional intelligence (EI) likely emerged around this time in species such as Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis. EI heralds the dawn of a new era where emotional intelligence began to take a recognizable shape.

Analysis: With indications of complex social structures, more potential for language, and advanced tool-making abilities, these species navigated their world with a level of social cognition and emotional awareness that surpassed their predecessors. Their ability to cooperate in hunting, share resources, care for the injured or ill, and possibly mourn their dead, points towards an emerging capacity for understanding the emotional states of others, fostering group cohesion and survival.

References

Full Emotional Intelligence:

- Source: Spikins, P. (2015). “How Compassion Made Us Human: The Evolutionary Origins of Tenderness, Trust and Morality.” Pen and Sword.

- Summary: This book discusses the evolution of emotional intelligence and compassion in early humans, providing evidence for the emergence of these traits in species such as Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals.

Complex Social Structures and Potential for Language:

- Source: Wynn, T., & Coolidge, F. L. (2011). “How To Think Like a Neandertal.” Oxford University Press.

- Summary: This book explores the cognitive abilities of Neanderthals and their predecessors, including the development of social structures and the potential for language.

Advanced Tool-Making Abilities:

- Source: Arsuaga, J. L. et al. (2014). “The Early Pleistocene Skeleton from the Sima de los Huesos Cave (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain).” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(16), 6014-6019.

- Summary: This article discusses the advanced tool-making abilities of Homo heidelbergensis, providing evidence of their cognitive sophistication.

Social Cognition and Emotional Awareness:

- Source: Dunbar, R. I. M. (1998). “The Social Brain Hypothesis.” Evolutionary Anthropology, 6(5), 178-190.

- Summary: This paper presents the Social Brain Hypothesis, which posits that the size of the human brain is related to the complexity of social structures and emotional awareness.

Cooperation in Hunting and Caring for Injured:

- Source: Pettitt, P. (2011). “The Palaeolithic Origins of Human Burial.” Routledge.

- Summary: This book provides evidence of early human burial practices and care for the injured, indicating a level of social and emotional cognition.

Emerging Capacity for Understanding Emotional States:

- Source: Tomasello, M., & Call, J. (2007). “The Gestural Communication of Apes and Monkeys.” Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Summary: This book explores the evolution of communication and the understanding of emotional states in primates, shedding light on the early development of these capacities in humans.

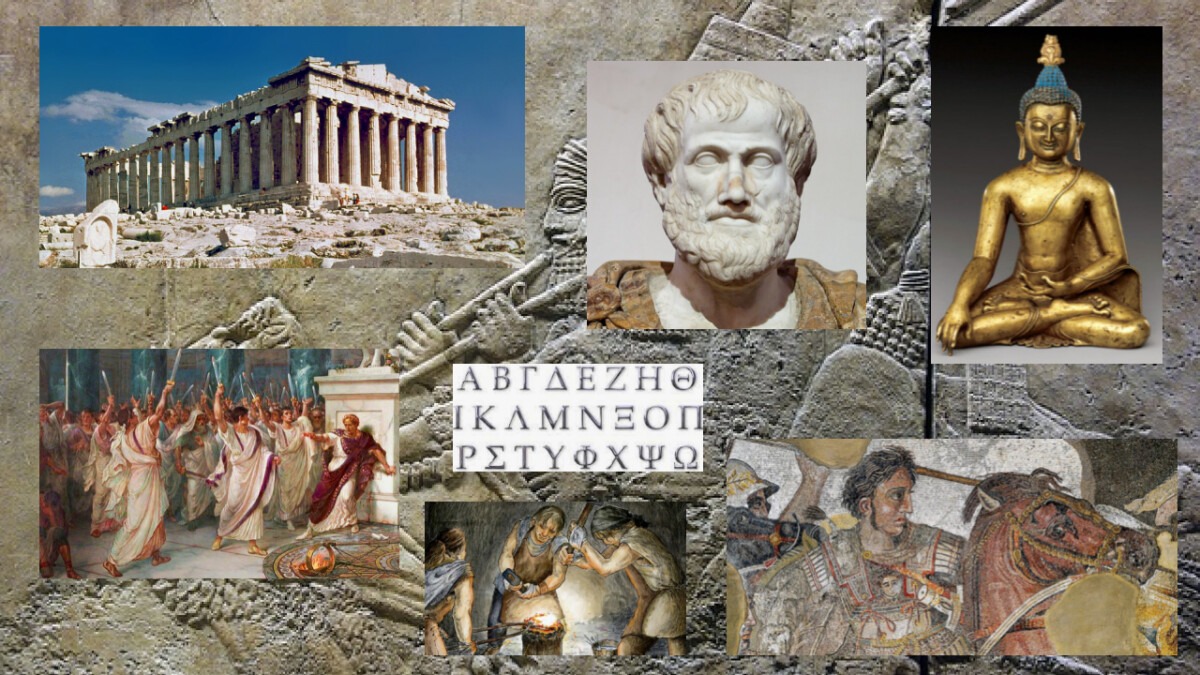

NSLCA Candidate: Homo heidelbergensis, an important figure in human evolution, represents a notable advancement over its predecessor, Homo erectus and Homo antecessor. Emerging around 640,000 years ago, they exhibited a larger brain capacity, averaging about 1,100 to 1,400 cubic centimeters, which facilitated more complex thought processes and behaviors. This increase in brain size is correlated with evidence of more sophisticated tool use, particularly the development of the Levallois technique, which allowed the production of diverse and specialized tools. Unlike Homo erectus, who primarily used simple stone flakes, Homo heidelbergensis crafted tools that were pre-planned and could be retouched and reused. Physically, they were more robust than Homo erectus, with a sturdier skeletal structure that supported a larger musculature, likely an adaptation to the colder climates encountered as they spread across Europe. Furthermore, Homo heidelbergensis is credited with the earliest potential evidence of constructed shelters and the systematic use of fire, suggesting a significant leap in technological and social practices, including possibly the earliest forms of communal living and hunting strategies. These traits mark Homo heidelbergensis as a crucial intermediary between earlier hominins and later species such as Neanderthals and modern humans.

- Brain Size: 1,100 to 1,400 cc (humans=avg=1,350; 1,200 to 1,500 cc)

- Brain to Body EQ: 4.5 to 5.5 (humans=7.4 to 7.8)

- Evolved in Africa about 770,000 YA, spread to Europe by 500,000 YA.

- Spread through Africa, Europe, and Asia. Last known: Africa until about 200,000 YA.

| Male | Female | |

| Avg. Height | 5’9″ | 5’2″ |

| Avg. Weight | 136 lbs | 112 lbs |

Proto-clothing, encompassing basic garments such as animal skins and possibly decorative natural materials, likely emerged among hominins around 600,000 years ago, with Homo heidelbergensis being a probable early adopter. This species, experiencing diverse and often colder climates across Europe and Africa, may have utilized simple clothing as a practical response to environmental challenges.

Analysis: The evidence for early use of clothing, while direct only for Homo sapiens and Neanderthals around 100,000 years ago, can be inferred for earlier hominins through indirect markers. The Last Common Ancestor (LCA) of Neanderthals and modern humans, dating back approximately 600,000 years ago, introduces the possibility that simple forms of clothing might have been in use from this point forward. This assumption is based on the survival needs in varying climates and the sophistication of tool use seen in Homo heidelbergensis. Additionally, the emergence of Homo antecessor around 1.2 million years ago and the sophisticated behaviors observed in Homo erectus, suggest that the use of clothing could be reasonably extended back as far as 1.5 million years ago, albeit more speculatively. Conversely, earlier hominins such as Homo habilis, with their limited tool use and milder environmental conditions, likely did not develop clothing.

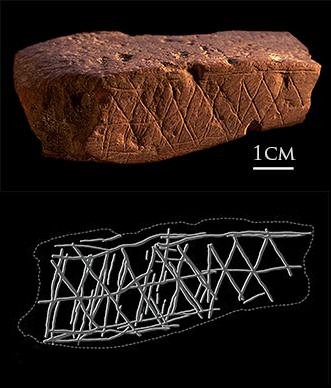

Transcendental Intelligence (TI) likely emerged around this time in species like Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis. Species such as these mark a compelling case for the early development of TI: the ability to store information outside the mind and across generations. This would likely take the form of stories, art, or something like a symbolic marking of an area used as a warning to stay away.

Analysis: Although direct evidence of art or jewelry from this era remains elusive, the sophisticated crafting techniques observed in later Neanderthal and Denisovan artifacts, suggest advanced cognitive abilities capable of TI including symbolic thought and advanced tool making. Denisovans are thought to have split from Neanderthals in Europe about 450,000 years ago, and Homo sapiens branched off in Africa about 315,000 years ago. The speculation that TI developed during this time is grounded in the understanding that the cognitive prerequisites for such advancements—complex problem-solving, abstract thinking, and perhaps rudimentary forms of symbolic communication—were likely present.

Big History Thresholds: 1=Big Bang | 2=Stars&Galaxies | 3=Chemicals | 4=Solar System | 5=First Life | 6=TI | 7=Agrarian | 8=Science

Collective Learning: The 6th threshold in Big History is Collective Learning, what I’ve dubbed Transcendenal Intelligence, the storing of information outside our minds. While Big History has this step set about 200,000 years ago as Homo sapiens emerged, I’ve moved it back to Homo heidelbergensis before Neanderthals and us branched off. After the publication of Big History, neanderthal art was discovered, indicating symbolic thought which might imply TI abilities. It’s important to note that very early collective learning likely emerged in Homo habilis or earlier.

NSLCA: The Neanderthal-Sapien Last Common Ancestor was likely Homo heidelbergensis or Homo antecessor.

Analysis: Before the discovery of Homo antecessor in the 1990s, Homo heidelbergensis was considered the primary candidate for the NSLCA due to its chronological and morphological position in the human lineage. The discovery of Homo antecessor, with its more modern-looking facial features, has intensified debates around the NSLCA’s identity. Recent scholarly speculation, influenced by the anatomical closeness of antecessor to modern humans and the larger brain of heidelbergensis, suggests a potential hybrid scenario where the NSLCA could represent a mix of traits from descendants of antecessor and contemporaneous heidelbergensis. This hybrid theory, while speculative, aligns with genetic evidence of interbreeding among Homo species.

Homo heidelbergensis first appeared in Africa around 770,000 to 650,000 years ago, while Homo antecessor emerged in Spain about 1.2 million years ago. If Homo antecessor is confirmed as our direct ancestor, this would imply that modern human features such as a flatter face and protruding nose may have evolved much earlier than previously thought, potentially as early as 1.2 million years ago. This scenario would also suggest complex migratory and evolutionary dynamics, possibly involving a back-migration of antecessor or its descendants into Africa, where the NSLCA would have emerged. This area remains a hotbed of research as new fossil discoveries continue to reshape our understanding of early human history.

True symbolic thought emerges before 430,000 BCE: The discovery in 2018 of Neanderthal art dating back to 68,000 years ago, proved symbolic thought in Neanderthals. It also indicates strongly that symbolic thought evolved in or before our common ancestor about 430,000 years ago. This must be true unless either they evolved it separately in an example of convergent evolution or we’re wrong about the art, meaning we’re wrong about our idea that humans were not in Spain until after that art. (see my Occam’s Razor article.)

See Beyond the Brain: Reassessing Neanderthal Intelligence, for more information. Humans and Neanderthals had a common ancestor about 430,000 BCE (current estimates range from 430,000 to 450,000 BCE). Humans did not evolve from Neanderthals, but both are the current evolution of a common ancestor: Homo Heidelbergensis. After the split, Homo Sapiens and Neanderthals interbred up to and as recently as 29,000 BCE. Through DNA testing we can identify DNA that came from interbreeding with Neanderthals. They built shelters, wore clothes, used tools, and spoke. Neanderthal DNA in modern humans is the highest in East Asians, intermediate in Europeans, and lower in Southeast Asians.

- Class: Mammal; Genus: Homo; Diet: Omninivore

- Brain Size: 1,200 to 1,700 cm³ (humans=avg=1,350; 1,200 to 1,500 cm³)

- Brain to Body EQ: 4.5 to 5.5, but maybe 6.2, or even 7.9? (humans=7.4 to 7.8)

- Evolved in Europe, spread to Africa and the Middle East.

- Last known: 29,000 BCE in the mountains of Polar Ural, northeastern part of Komi, Russian Federation.

References

- D’Anastasio, R., Wroe, S., Tuniz, C., Mancini, L., Cesana, D. T., & Boscaini, A. (2013). “Micro-Biomechanics of the Kebara 2 Hyoid and Its Implications for Speech in Neanderthals.” PLoS ONE, 8(12), e82261.

- Krause, J., et al. (2007). “The Derived FOXP2 Variant of Modern Humans Was Shared with Neandertals.” Current Biology, 17(21), 1908-1912.

- Wynn, T., & Coolidge, F. L. (2011). “How To Think Like a Neandertal.” Oxford University Press.

Discovered in the 1990s, this 400,000-year-old Homo heidelbergensis structure in France is believed to be a primitive hut or shelter made from wooden posts and branches. The structure is thought to have been built by Homo heidelbergensis. The shelter is estimated to be around 4-5 meters (13-16 feet) wide and 6-7 meters (20-23 feet) long. It’s believed to have been constructed using a simple framework of wooden posts, with branches and leaves used to create a roof and walls. While the above image is a minimalist artist representation, the following is more likely what their camp looked like.

Homo heidelbergensis: Long spears made hunting large animals more safe. The oldest wooden spears found so far were found in Germany and dates to circa 400,000 BCE. In fact, they are currently the oldest known wooden artifacts. The find included 3 wooden spears, stone tools, and the butchered remains of more than 10 horses.

These spears have the same qualities as modern tournament javelins and can be thrown over 200 feet. The workmanlike qualities of the heavily worked wood were similar to modern javelins where the heaviest thickest part of the spear, the center of gravity, is in the front third.

Speculative branch of humans. Maybe a long lost hybrid: In the evolving tapestry of human history, the emergence of Homo naledi represents a captivating mystery that challenges traditional narratives of linear progression. Positioned within the intricate web of human evolution, Homo naledi could exemplify a complex branch woven from ancient threads. Imagine a scenario where a group descended from late Australopithecus interbred with Homo erectus, resulting in a unique hybrid species. This hybrid lineage, embodying a blend of primitive and advanced traits, might have thrived alongside other hominins, contributing to a rich mosaic of human diversity. The existence of Homo naledi, with its distinct blend of characteristics, suggests that our evolutionary past may not be a simple tree with neatly diverging branches, but rather a dense network of interconnected lineages, intermingling and evolving in response to the dynamic landscapes of ancient Africa. Such a perspective invites us to reconsider the complexity of human ancestry, highlighting the possibility of multiple, overlapping narratives of evolution driven by hybridization and adaptation.

Imagined image: Homa naledi. Left is circa 250,000 BCE. Right is circa 335,000 BCE. The later Homo naledi individual as appearing more human-like is somewhat speculative but can be supported by the evidence of their anatomical features and behaviors.

Survival: From about 335,000 BCE to 236,000 BCE in Eastern and Southern Africa (in woodlands and grasslands)

Size: 3’4″ to 4’5″ (a bit taller than modern chimpanzees)

Brain Size: around 510 to 600 cm³

Brain to Body EQ: 3.3 to 3.8 (humans=7.4 to 7.8)

The first humans evolved in Africa about 315,000 BCE. These first humans had most of the traits we identify as human including looking and thinking much as we do. They used brain power, innovation, and teamwork. They spoke and controlled fire. Their lives were complex. Over the next 250,000 years they evolved into us. By about 150,000 BCE our current capabilities were mostly evolved. Today’s humans have essentially the same DNA as humans from circa 60,000 BCE.

With the emergence of Homo sapiens, the landscape of consciousness witnessed the dawn of Transcendental Intelligence (TI)—a level of cognitive and cultural sophistication unmatched in the natural world. The 2018 discovery of Neanderthal cave paintings, which dates back over 64,000 years, compellingly extends the evidence of TI to at least 400,000 years ago, demonstrating advanced cognitive abilities such as symbolic thought and artistic expression.

This era, spanning several hundred thousand years, is distinguished not only by the development of complex languages and profound knowledge systems but also by the ability to actively transmit culture, art, and technology. Homo sapiens harnessed TI to shape their environments, conceive abstract concepts, and establish societies with intricate social norms and belief systems. Similarly, Neanderthals, with their complex behaviors and symbolic practices, demonstrated a capacity for TI that suggests a broader cognitive potential within the genus Homo. As modern AI systems begin to replicate aspects of TI in information processing and communication, they reflect humanity’s ongoing quest to understand and replicate the depths of its own intelligence. However, the quintessential human experiences of consciousness, emotion, and cultural identity remain unparalleled, emphasizing the profound mystery and uniqueness of human cognition and its evolution over millennia.

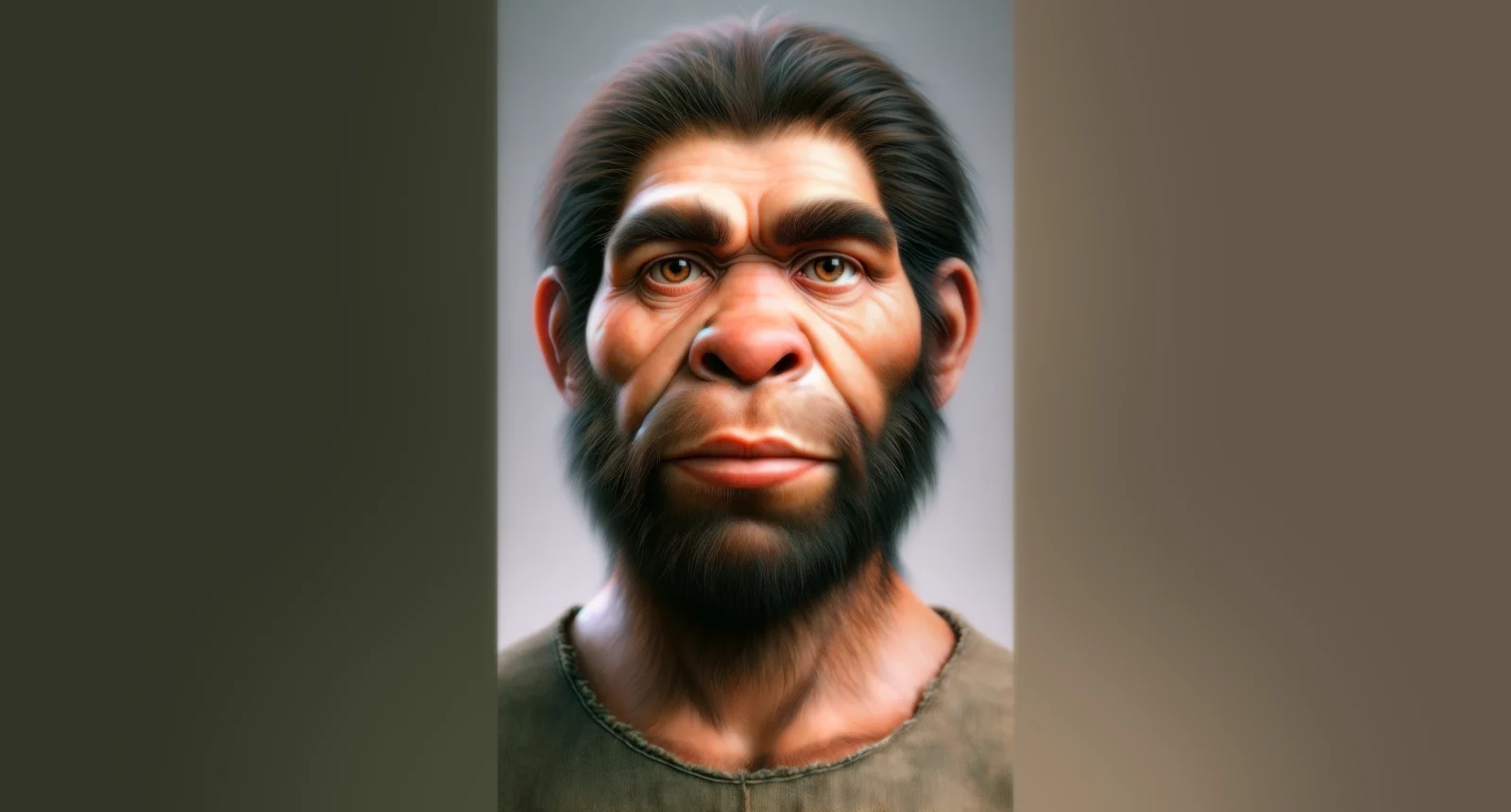

Imagined image: two Homo sapiens males from different stages of human evolution are featured. The first figure represents Homo sapiens from about 300,000 years ago, and the second from about 100,000 years ago, each with distinct features representative of their times.

Neanderthals and denisovans in the genus Homo had a common ancestor about 370,000 BCE (current estimates range from 250,000 to 500,000 BCE). Though neanderthals, denisovans, and sapiens share a common ancestor, they didn’t evolve directly from each other. That common ancestor from which all three evolved from was likely a later Homo heidelbergensis. Although some research suggest Denisovans branched from an early neanderthal. If Denisovans branched from an earlier Homo heidelbergensis, it suggests modern cognitive abilities like symbolic thought may have emerged much earlier than previously believed, which aligns with discoveries of early art currently under investigation. Some suggest denisovans branched from Homo erectus, if that’s true but I don’t think it is, that pushes the evolution of our modern brains back to about 1 million years ago. Either way, it’s clear our current anthropomorphic bias has painted a cloudy picture. It’s much more likely that many of these species were roaming around with similar cognitive abilities. Occam’s Razor suggests that’s more likely than all these species evolving “intelligence” in such a short time.

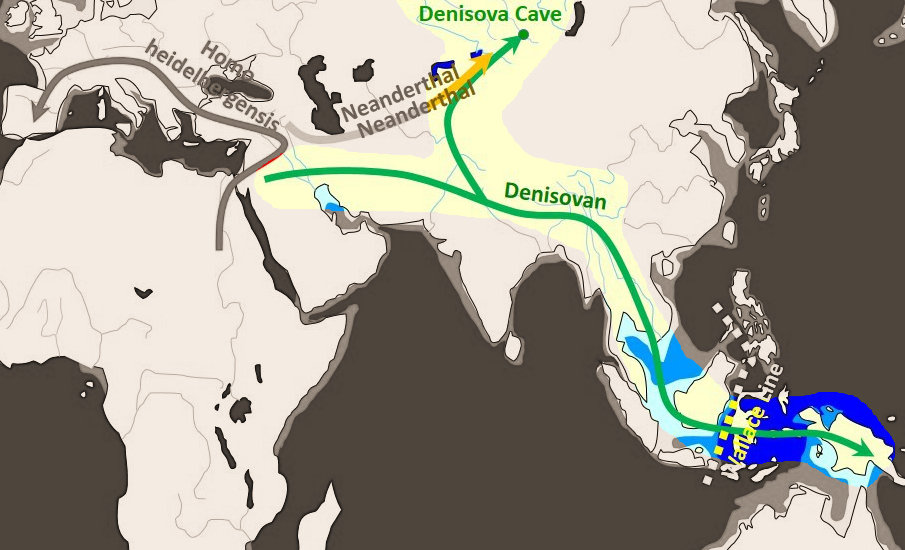

Long after the three species were on Earth, they interbred from time to time. Through DNA testing we can identify DNA that came from interbreeding with both. The highest percent of denisovan DNA in modern humans is in Melanesian population ranges; it ranges from 4 to 6 percent, lower in other Southeast Asian and Pacific Islander populations, and nearly undetectable elsewhere in the world.

Denisovans became extinct about 40,000 BCE, the last surviving in Siberia. They built shelters, wore clothes, used tools, and spoke. Late Homo heidelbergensis, neanderthals, denisovans, and sapiens all likely looked very similar: a combination of the wide variety seen in modern humans.

When Homo sapiens first emerged, their population in Africa was likely just a few hundred thousand, while the total hominin population, including other species like Neanderthals and Homo heidelbergensis, may have ranged from 1.1 to 2.1 million. During this period, Homo sapiens were primarily found in Africa, while other hominins occupied broader ranges across Eurasia, with Neanderthals and Denisovans adapting to their environments with sophisticated tool-use and social structures. The early hominin distribution and interaction remain unclear, and this narrative, while speculative, helps us imagine the ancient world, highlighting the need for caution in interpreting these ancient population dynamics. Check out A New Look at Ancient Hominin Numbers: A Speculative Journey for more information.

Homo rhodesiensis, often regarded as Africa’s counterpart to Europe’s Homo heidelbergensis, represents a pivotal species. Discovered in Kabwe, Zambia, the species exhibits a mix of robust and modern traits with a large brain size and advanced tool use, reflecting significant cognitive capabilities.

Interbreeding Analysis: The evolutionary journey of Homo rhodesiensis might highlight well the complex nature of species development within the genus Homo. As with other human species, the lines between Homo rhodesiensis and its contemporaries were not always clear-cut. Genetic and morphological evidence suggests that early humans, including Homo rhodesiensis, likely engaged in interbreeding with closely related species. This interbreeding could have occurred as they encountered each other in overlapping territories, facilitated by their innate “pioneering spirit” — an inherent drive to explore and adapt to new environments.

Pioneering Spirit and Its Consequences: The inherent exploratory nature of Homo rhodesiensis and other early humans is a defining characteristic of the genus. This “pioneering spirit” not only allowed these hominins to traverse vast and varied landscapes but also to interact and genetically mingle with other emerging human species. Unlike earlier primates that may have been more restricted to specific environments, the mobility of Homo rhodesiensis enabled a dynamic exchange of genes and cultures, potentially accelerating the pace of human evolution.

Analysis: While the exact paths of migration and interaction are still subjects of active research, the adaptability and innovativeness of Homo rhodesiensis likely played a crucial role in their survival and evolutionary success. Their ability to innovate technologically and adapt culturally might have paved the way for the emergence of Homo sapiens in Africa. As such, Homo rhodesiensis not only contributes to our understanding of human evolution but also exemplifies the interconnectedness and fluidity of species boundaries within the genus Homo.

Found in central India, these cupules (circular hollows on rock surfaces) are among the earliest known forms of rock art. They were likely created by a species like Homo erectus or Homo heidelbergensis and not Homo sapiens. Homo sapiens are not known to be in India until around 40,000 years ago. Homo erectus is known in India as early as 1.7 million years ago and Homo heidelbergensis around 300,000 years ago. If Homo heidelbergensis is confirmed, that moves the evolution of symbolic thought back to before 700,000 years ago. If Homo erectus is confirmed, that moves it back to well before 2 million years ago.

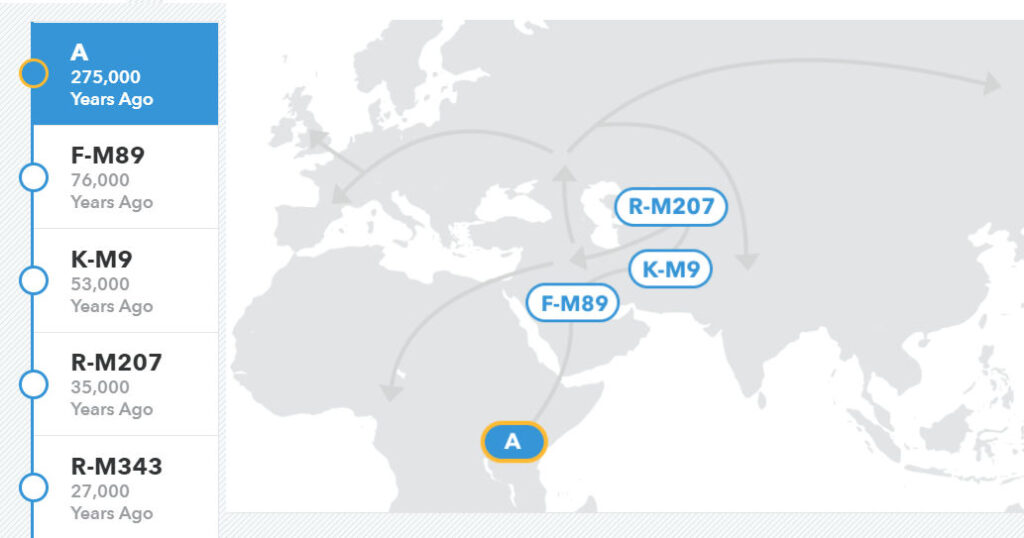

All humans today share a single grandpa, circa 275,000 BCE. We know this because all humans alive today share our ancestor’s haplogroup A genes — from our Y chromosome. He was one of many thousands of men living in eastern Africa. Many paternal lines survived for many generations but ultimately over time all the other male lineages died out. Adam’s descendants met our Eve about 100,000 years later–about 4,000 generations later.

Discovered in 2013 and first dated in 2017, Homo naledi and humans coexisted in South and East Africa from our emergence around 315,000 years ago until their extinction about 236,000 years ago. It is possible that we share a common ancestor with them, but research is pending. Homo naledi lived in South Africa from 335,000 to 236,000 years ago, and our earliest evidence for Homo sapiens put us originating in East Africa.

Imagined Image: A speculative scene of several Homo naledi individuals around a natural fire source, set in an ancient South African landscape. This visualization highlights the social and survival aspects of early hominin life.

Survival: From about 335,000 to 236,000 years ago in South Africa.

Size: 4’9″ to 5’3″

Brain Size: around 465 to 600 cm³

Brain to Body EQ: 3.3 to 3.8 (humans=7.4 to 7.8)

Homo heidelbergensis lived in Africa, Europe and Asia from 700,000 to 200,000 years ago. They coexisted with humans in Africa, Europe, and Asia from our emergence around 315,000 years ago until their extinction about 200,000 years ago.

Imagined Image: A Homo heidelbergensis campsite a few thousand years before they went extinct, set in a lush European forest. The scene includes several individuals in a communal setting, showcasing aspects of their life and environment.

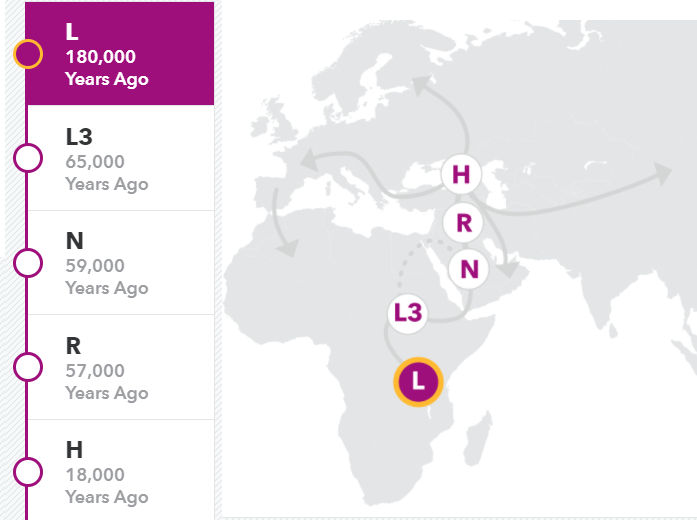

All humans today share a single grandma, circa 175,000 BCE. We know this because all humans alive today share our ancestor’s haplogroup L genes — from our X chromosome. She was one of many thousands of women living in eastern Africa. Many maternal lines survived for many generations but ultimately over time all the other female lineages died out.

By circa 150,000 BCE, the size of our brain and it’s capabilities matured. Think about this. A human born today and a human born in 150,000 BCE had roughly the same mental and physical capacities. This includes all of our traits including our need for attention and power, our ingenuity, our gullibility to believe things, and our intolerance of the unknown and different. If a human from this time landed in a modern morgue, the doctor performing yet another autopsy would most likely think it was a modern human.

How many times since 150,000 BCE did humans create new religions and Gods? How many times did they discover or invent things that were then lost for thousands of years? Human knowledge builds on previous knowledge, but only if it can be passed down, and survive the test of time. It’s reasonable to believe that various forms of writing and labels were developed and lost countless times. Many interesting advances developed, and lost. No doubt, the stubborn belief in myth or dogma has led directly to the suppression of various human advances countless times. Many times through the use of war and genocide.

Let’s look at just one modern human example. We know the Greeks several thousand years ago knew the Earth was a globe. Over time, the information, the advance, was lost because of the belief in myth and a desire to control others.

In the lush landscapes of northeastern China, the discovery of the Homo longi skull has opened new chapters in our understanding of human evolution. This skull, dating back to approximately 146,000 years ago, represents a pivotal moment in prehistory. Homo longi, also nicknamed “Dragon Man,” showcases a unique blend of archaic and modern traits—marked by a large, broad face and pronounced brow ridges. This solitary but exceptionally well-preserved fossil suggests that Homo longi could have emerged as a distinct species much earlier, potentially around 200,000 to 300,000 years ago. The timing and features of Homo longi indicate it might represent an earlier migration out of Africa, preceding or running concurrent with other known migrations. The implications extend further, hinting at a possible influence from Homo antecessor, which may have shaped the evolutionary path of humans more profoundly than previously recognized. The Homo longi fossil, while singular, provides a critical piece of the puzzle in tracing the intricate web of human ancestry and migration across continents.

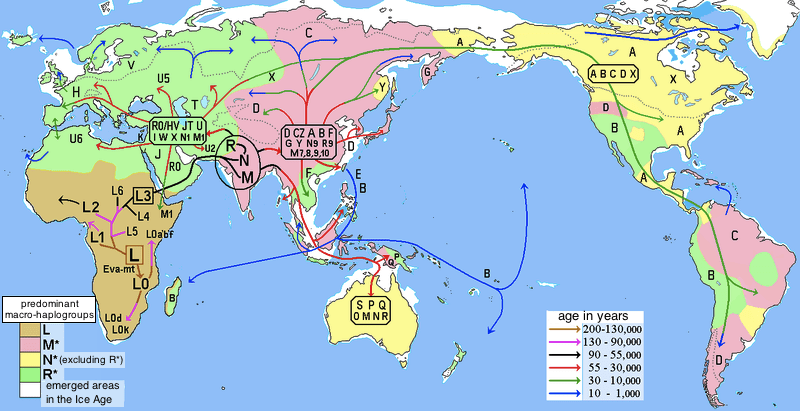

The “out of Africa” migration took place in many waves of which two are widely recognized: 130,000 to 100,000 BCE, and the Southern Dispersal around 70,000 to 50,000 BCE. Through genetic DNA testing we know that none of the genetic differences prior to circa 70,000 BCE exist in today’s humans.

Denisovan: This bracelet dates from 70,000 to 40,000 BCE. It was discovered inside the Denisova Cave beside ancient human remains. The Denisova Cave is a cave located in Siberia, Russia. Other cave finds include woolly mammoth and woolly rhino bones. Scientists say there is evidence that the bracelet’s maker used a drill. This is the earliest known example of advanced drilling in the world.

Head of the museum Irina Salnikova said: ‘The skills of its creator were perfect. Initially we thought that it was made by Neanderthals or modern humans, but it turned out that the master was Denisovan.” This has led to speculation that these earliest humans, Denisovans, were more technologically advanced than previously thought. If true, it might be that the Denisovans were more skilled than Homo sapiens and Neanderthals of the time.

Like Neanderthal DNA, Denisovan DNA exists in modern humans. Non-African East Asians and Europeans have about 2% Neanderthal DNA. Modern Melanesians derived about 5% of their DNA from Denisovans.

The Sentinelese are believed to have been isolated since the last major initial human migrations out of Africa 60 to 70 thousand years ago. Their isolation has likely preserved unique genetic traits. The Sentinelese are related to other indigenous peoples of the Andaman Islands, such as the Onge, Jarwa, and Great Andamanese. Studies on these groups indicate that they have some of the earliest genetic markers found in Asia. The genetic diversity among the Andamanese tribes, including the Sentinelese, is thought to be low due to their small population sizes and long-term isolation. Due to their isolation, the Sentinelese may lack immunity to common diseases found elsewhere–a significant concern.

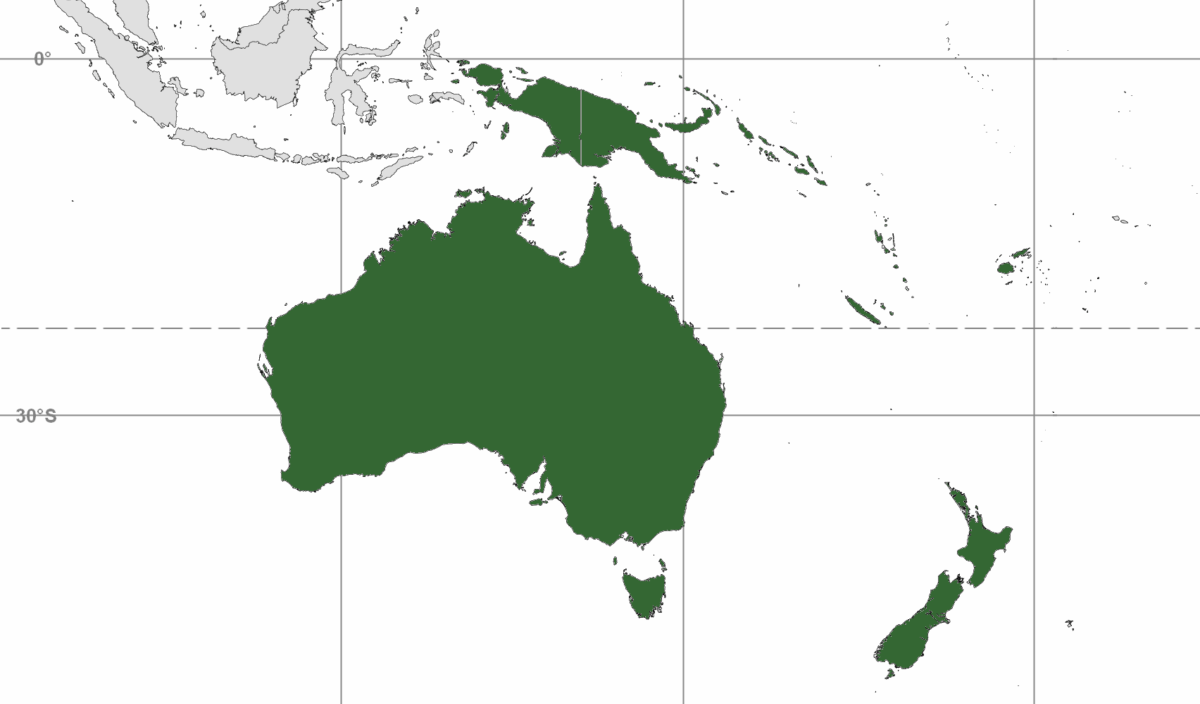

Long before the sails of European explorers dotted the horizon, the Australian continent witnessed the arrival of its first human inhabitants. Archaeological evidence, such as ancient tools and cave art, suggests that people arrived in Australia at least 65,000 years ago, marking one of the earliest known human migrations out of Africa. These first Australians, ancestors of today’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, developed rich cultural traditions and adapted to the diverse environments of the continent, from its arid deserts to its lush coastlines. Their legacy is a testament to human resilience and ingenuity, shaping the land that would later be known as Australia for tens of thousands of years before European contact.

Discovered in 2019, Homo luzonensis inhabited the Luzon area north of Manila in the Philippines from at least about 67,000 to about 50,000 years ago. While current evidence suggests that Homo luzonensis may have become extinct before the documented arrival of Homo sapiens around 35,000 to 40,000 years ago, the exact timing of their extinction remains uncertain.

Lineage: Similar to Homo floresiensis, the luzonensis people are not likely descendants of Homo heidelbergensis. It is more plausible that they descended from an earlier ancient human, possibly from the Dmanisi population, an early Asian Homo erectus lineage, or potentially even directly from Homo habilis. However, any direct link to Homo habilis is speculative, but particularly interesting given the small brain size and stature of the luzonensis people.

Imagined Image: A small group of Homo luzonensis in a dense tropical forest on Luzon. This visualization emphasizes their survival strategies and interactions within their lush habitat.

Survival: From about 50,000 to 67,000 years ago (possibly earlier) in Luzon area, near Manilla, Philippines.

Size: 3′ 3″ to 3′ 7″ (same size or smaller than Homo floresiensis)

Brain Size: Estimated around 400 cm³ (about the same size as Homo floresiensis).

Brain to Body Encephalization Quotient (EQ): Ongoing research but likely about the same as Homo floresiensis, about 3.2.

The modern human DNA evolved sometime between 71,000 and 51,000 BCE. Imagine that. A human baby born today, and a human baby born in 60,000 BCE have nearly indistinguishable DNA. There are differences but essentially humans are the same now as they were then. The popular website 23andme.com focuses on 23 changes in DNA that signify your ancestors recent migration. 23andMe.com, ancestry.com, and many others identify differences for their customers. Finally, the medical community is currently in an intense wave of identifying genetic differences that lead to medical problems with the idea of early diagnosis, prevention, and through the use of mRNA correction.

Through mtDNA sequencing, we currently believe the most recent common ancestor of all the Eurasian, American, Australian, Papua New Guinean, and African lineages dates to between 73,000 and 57,000 years ago.

Through minor DNA changes, we know which early humans have descendants alive today. This successful “out of Africa” migration, the Southern Dispersal, took place around 70,000 to 50,000 BCE. Our ancestors proceeded to colonize all the continents and larger islands, arriving in…

- Eurasia circa 60,000 BCE

- Australia circa 65,000 BCE

- South America circa 30,000 BCE

- North America circa 28,000 BCE (31,000 to 29,000 BCE)

- Hawaii, Easter Island, Madagascar, and New Zealand circa 300 to 1280 CE

Dark Skin Diversification: Africa’s intense UV radiation continues to select for darker skin, which protects against UV-related damage and helps in managing folate levels. The mention of some populations developing even darker skin tones could be linked to local environmental adaptations within the continent.

Cognitive Revolution

50,000 BCE – 70,000 BCE. Population range: 500,000 to 2.5 million.

Given the uncertainties and lack of direct data, the following are speculative estimates.

- Africa-Middle East: 50-60% or 600,000 to 1 million people

Africa, being the origin of modern humans, likely had the highest population density at this time, particularly in Sub-Saharan regions which were more conducive to human habitation due to their climate and available resources. - Asia: 40% or 200,000 to 400,000 people

- Europe-Mediterranean: 10% or 50,000 to 100,000 people

- The Americas: 0.

- Oceana-Australasia: 1% or 10,000 to 15,000 people

The initial colonization of Australia around 50,000 BCE by modern humans involved small, isolated groups who managed to navigate sea crossings, leading to a very low initial population density. The rest of the remote islands of Oceania were among the last to be reached by humans.

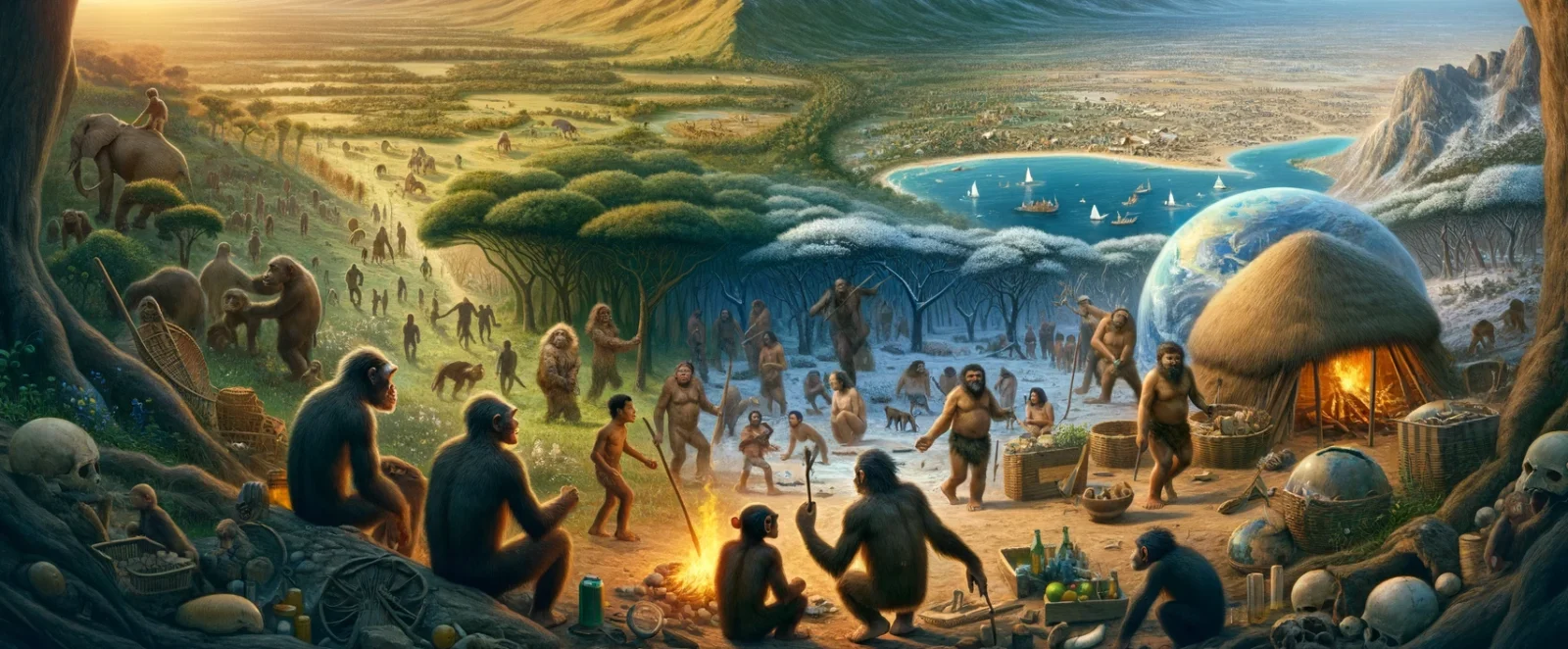

A Shared Earth! Neanderthals-Hobbits-Flourensis

Around this time, Homo sapiens shared the Earth with other hominin species. Neanderthals were still widespread in Europe and parts of western Asia. In Asia, particularly on the islands of Indonesia, Homo floresiensis, often referred to as the “Hobbit” due to their diminutive stature, survived until about 50,000 years ago. Additionally, Denisovans, a less visually documented but genetically distinct group, also roamed Eurasia, leaving behind a genetic legacy that persists in modern humans, particularly among populations in Melanesia.

Homo erectus and humans last coexisted in Javanese in Asia around 50,000 years ago.

Imagined image above: A late-stage Homo erectus individual in Java, Indonesia, focused on crafting a tool from volcanic rock near a simple fire, set within the lush tropical rainforest. This visualization aims to capture the essence and appearance of Homo erectus during this late stage of their existence.

Discovered in 2003, Homo floresiensis (also known as the “Hobbit”) inhabited the island of Flores in Indonesia from 190 to 50 thousand years ago. Humans arrived about 50,000 years ago and may be the reason for their extinction.

Lineage: Most likely not a Homo heidelbergensis, but a descendant species from an earlier ancient human. Perhaps from the very successful Dmanisi people, an Asian Homo erectus lineage, or perhaps even directly from Homo habilis, which might be the original Earth roamer. The link to Homo habilis is speculative and based on the smaller brain size and stature of the floresiensis people.

Imagined Image: A small group of Homo floresiensis in their natural habitat on the island of Flores, engaging in daily activities around a communal fire and interacting with the local fauna. This scene captures their unique adaptations and social behaviors within a lush volcanic landscape.

Survival: From about 190,000 BCE to 50,000 BCE, primarily on the island of Flores, Indonesia.

Size: Approximately 3’6″ to 3’10″ (a bit shorter than the pygmy in Africa at 4’11”).

Brain Size: 380 to 420 cm³.

Brain to Body Encephalization Quotient (EQ): Research ongoing, but roughly 3.2 (habilis=3.3 to 3.8; humans=7.4 to 7.8).

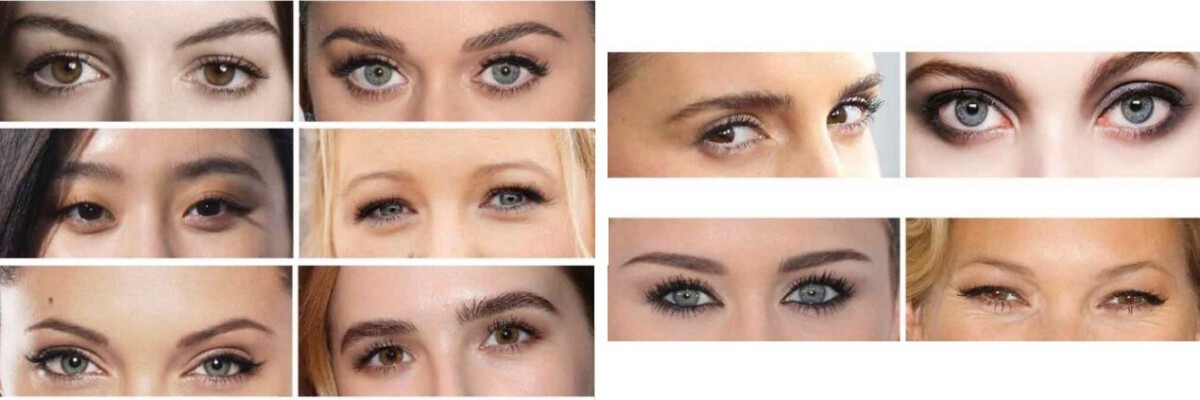

The feature of the epicanthic fold, particularly prevalent among East Asian populations descended from Haplogroup A, is an adaptation to cold, windy, and bright environments encountered as humans migrated northward from Africa. This phenotype likely developed to protect the eyes from frostbite and snow blindness, showcasing how genetic diversity within human lineages adapted to specific environmental challenges.

Denisovans and humans coexisted in Siberia from about 194,000 to around 40,000 years ago. While their exact cause of extinction remains debated, competition with modern humans and climate change are thought to be contributing factors.

Imagined image: Set in Siberia around 45,000 years ago, a group of Denisovans is depicted in their winter camp, surrounded by a snow-laden forest. They are dressed in heavy fur clothing, complete with detailed, fur-lined boots, essential for the extreme cold. Their camp, featuring sturdy shelters made from wood and animal skins, centers around a warm, bustling fire, highlighting their advanced survival strategies and social cohesion in the harsh climate.

Homo neanderthalensis: Neanderthals and humans coexisted in Europe and Asia until around 40,000 years ago. While their exact cause of extinction remains debated, competition with modern humans and climate change are thought to be contributing factors.

Imagined image: Left is a neanderthal, right a human. Just as human looks vary widely, Neanderthals did too. This is perhaps one way neanderthals might have looked. The likely looked a bit more human than this too, but this gives you a good idea of the differences.

Current understanding suggests that the diverse skin colors among modern humans, ranging from dark brown to fair, evolved multiple times both within Africa and as Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa. This variation is driven by natural adaptation to varying levels of UV radiation exposure in different populations, a process that typically unfolds over thousands of years.

Modern humans predominantly descend from a successful migration wave out of Africa that occurred around 50,000 years ago. Although there were earlier migratory events, this later exodus has been well-documented and significantly shaped our genetic makeup. Evidence suggests that these migrants interbred with earlier waves of sapiens as well as other hominin groups they encountered, notably including Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Skin color adaptation occurred in each migratory wave of Homo sapiens, as well as through interactions with other hominins. The process that most significantly affected modern skin colors began during these migrations and continued over a span of 20 to 30 thousand years. Cross-breeding among various waves of populations, which contributed to the diversity in skin pigmentation, was almost certainly a factor. Lighter skin tones primarily evolved in areas with reduced sunlight, especially after the Last Glacial Maximum, to facilitate vitamin D synthesis under conditions of lower UV radiation.

Note: The adaptation of skin color is intricately linked to the migration patterns of ancient humans. As populations spread from Africa into Europe, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Asia, their skin color adapted to local environmental conditions. Robust genetic evidence, particularly concerning alleles such as those in the SLC24A5 and SLC45A2 genes, supports these adaptations. This evolutionary trajectory underscores the complex interplay between genetics, diet, and environment in shaping one of the most visible aspects of human diversity.

The Mezhyrich community thrived in Ukraine, living in huts built from mammoth bones. These resourceful people used mammoth skulls, tusks, and bones to construct shelters covered with animal skins. They engaged in daily activities such as cooking, tool-making, and socializing, showcasing a harmonious, bustling life. The nearby rivers provided resources and sustenance, while their sophisticated structures indicated advanced social organization and cooperation.

Blue eyes emerging stands out as a striking example of a genetic mutation that spread across populations. Traced back to a single individual living between 6,000 and 8,000 BCE in the region near the Black Sea. The mutation involved is a specific change in the OCA2 gene, which alters the way melanin is produced in the iris. Originally, all humans had brown eyes, but this mutation led to the reduction of melanin in the iris, resulting in blue eyes.

As dairy farming became prevalent, particularly in Europe and some African communities, natural selection favored individuals who could digest lactose into adulthood. This genetic adaptation, known as lactase persistence, is a direct result of human cultural practices (dairying) and has had significant dietary implications.

Next >>

Evolution TL: March to Life > Evolution > Great Apes > Human > Consciousness > All to Us